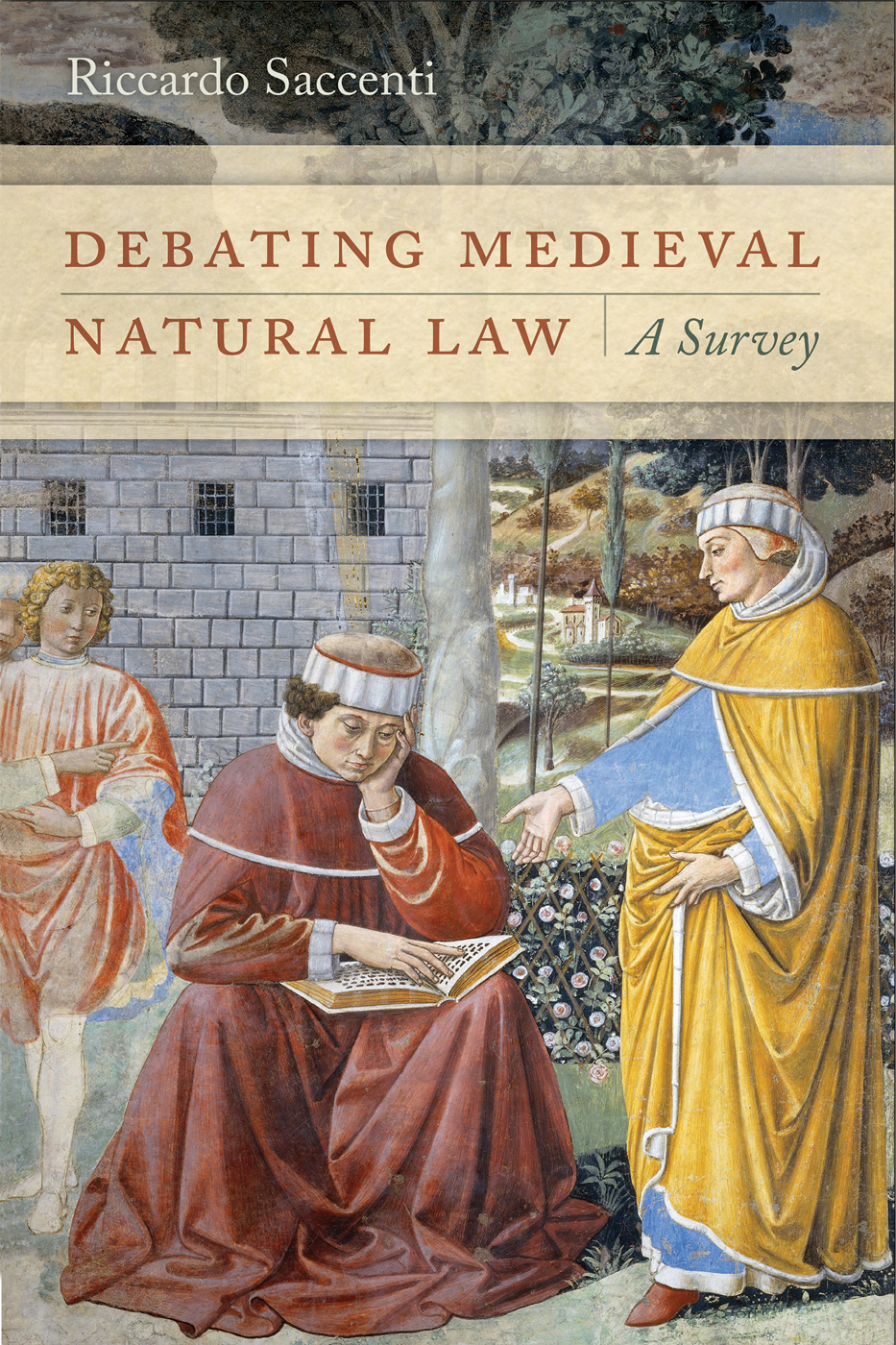

DEBATING MEDIEVAL NATURAL LAW

Debating Medieval Natural Law

A SURVEY

RICCARDO SACCENTI

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

www.undpress.nd.edu

Copyright 2016 by the University of Notre Dame

All Rights Reserved

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Saccenti, Riccardo, author.

Title: Debating medieval natural law : a survey / Riccardo Saccenti.

Description: Notre Dame : University of Notre Dame Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016028707 (print) | LCCN 2016032539 (ebook) | ISBN 9780268100407 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 0268100403 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780268100421 (pdf) | ISBN 9780268100438 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Natural law. | Law, MedievalInfluence.

Classification: LCC K460 .S23 2016 (print) | LCC K460 (ebook) | DDC 340/.112dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016028707

ISBN 9780268100438

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at .

To Donatella, for our love,

and to Matilde Maria, for her future

CONTENTS

I am in debt to the many people who supported the research and writing of this book, although of course I alone am responsible for its contents. This book is the first product of a research project concerning the relation between the historical development of the idea of natural law and the magisterium of the church. The Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII in Bologna has supported this research since 2012. Alberto Melloni, director of the Fondazione, took special interest in my research, offering invaluable suggestions and comments. I would like to express my deep gratitude for his support and his trust in my work. At the Fondazione my interest in natural law was shared by Cinzia Sulas, who always offered keen observations during our discussions. I am grateful to her for this exchange of ideas and for her kindness.

On several occasions, I presented and discussed the contents of this book with all my colleagues at the Fondazione in Bologna. With some of them I had the opportunity to discuss my research on a daily basis, and I profited greatly from their friendly notes and comments. I would like to thank especially Patrizio Foresta, Dino Buzzetti and Davide Dainese, as well as Pier Cesare Bori, who passed away before I completed my research project.

Several friends and colleagues read the manuscript and offered wise suggestions. I am grateful to Gianfranco Fioravanti, Christian Moevs, Timothy Noone, Constant Mews and Francesco Borghesi. I also would like to thank Julia Schneider for her essential and patient revision of the English text and Frederick Lauritzen for his stylistic advice. The anonymous reviewers who read the text during the peer review process offered useful comments, for which I would like to thank them. I also offer my gratitude to the staff of the University of Notre Dame Press for their care and assistance as I prepared the manuscript for publication.

Finally I would like to thank all the members of my family, who supported me during the months I spent studying the issue of medieval natural law. In particular, the love and patience of my wife, Donatella, and our little daughter, Matilde Maria, made it possible for me to complete this work. I dedicate this book to them.

Io, che son la pi trista, / son suora a la tua madre, e son Drittura, / povera, vedi, a fama e a cintura (For I, in sorrow first, / Am Justice, and my sister gave you birth / Though as you see, my clothes are of small worth).1 In these verses, Dante Alighieri offers an allegorical presentation of Justice and uses the image of three women to characterize three kinds of justice, namely, what medieval authors called natural law, or drittura (ius naturale), law of nations (ius gentium), and civil law (ius civile). According to Dante, these kinds of ius are deeply connected as ius naturale is the mother of ius gentium and the grandmother of ius civile.2

An ancient interpretation of Dantes thought juxtaposes Tre donne to Chacos words in Inferno 6.73: Giusti son due, e non vi sono intesi (Two are just, and no one heeds them).3 According to interpreters of the Divine Comedy such as Jacopo della Lana, the Anonymous Selmiano, and Pietro Alighieri, the two giusti no longer respected in Florence are those of law and custom, ius and mores, or those of divine and human law, fas (ius divinum et naturale) and ius gentium sive humanum.4 The reference here is to the opening pages of Gratians Decretum, where the author, quoting Isidore of Seville, explains that human nature is ruled by customs and laws and that natural law (ius naturale) is contained in the laws of Moses and in the Gospel. In fact, this law of nature corresponds to the Golden Rule of Matthew 7:12: All things therefore whatsoever you would that men should do to you, do you also to them. For this is the law and the prophets.5

The Florentine poet and his ancient commentators seem to have in mind a conceptual framework composed of ius naturale or drittura, ius gentium, ius civile, the Golden Rule, and divine will. Using this conceptual map, Dante places himself within a long and complex intellectual tradition to which several legists and decretists, theologians, and philosophers belong. Starting with Gratian, several authors have dealt with the way in which ius naturale could be considered the basis of both the legal and moral orders. These authors developed an understanding of this peculiar kind of ius that encompassed its very plurality: it is a rule, a moral principle, a power proper to human nature, an instinct. Ius naturale became a crucial topic in medieval culture, and its history reflects the developments and turns in political, economic, and religious life. Harold Berman, Paolo Prodi, and other historians have offered detailed analyses pointing out the place that medieval discussions of ius naturale occupied in the historical process. Following the last decades of the eleventh century, radical changes occurred in the cultural, political, and ecclesiastical structures and institutions of Latin Europe.6

Many scholars have devoted themselves to the study of the medieval history of the ideas of natural law and natural rights. This literature grew rapidly in the twentieth century, especially after World War II, when human rights became a focus of moral and legal cultures. The aim of this literature was and continues to be to define the features of the evolution of these ideas looking back to the medieval roots of modern rights doctrine. In its presentation and debate of the various interpretations of the medieval development of ius naturale and lex naturalis, this literature has deepened our understanding of the intellectual background against which Dantes allegorical representation of natural law stands.

Evaluating the main results of this lengthy research requires clarifying concepts and ideas, stressing continuities and discontinuities, and delineating the limits of medieval ideas of natural law and natural rights and their contemporary heir, human rights. This book offers a critical review of the way in which we look at the crucial conclusions that scholars reached in their inquiries. My goal is to establish the

Next page