IMAGES

of America

MICHOUD

ASSEMBLY FACILITY

In 1912, a lone horse-drawn buggy makes it way down a dirt road. At right are the remains of the smokestacks used in the sugar refinery process at the Michoud Plantation, now slowly being consumed by overgrown vegetation. (Courtesy of NASA.)

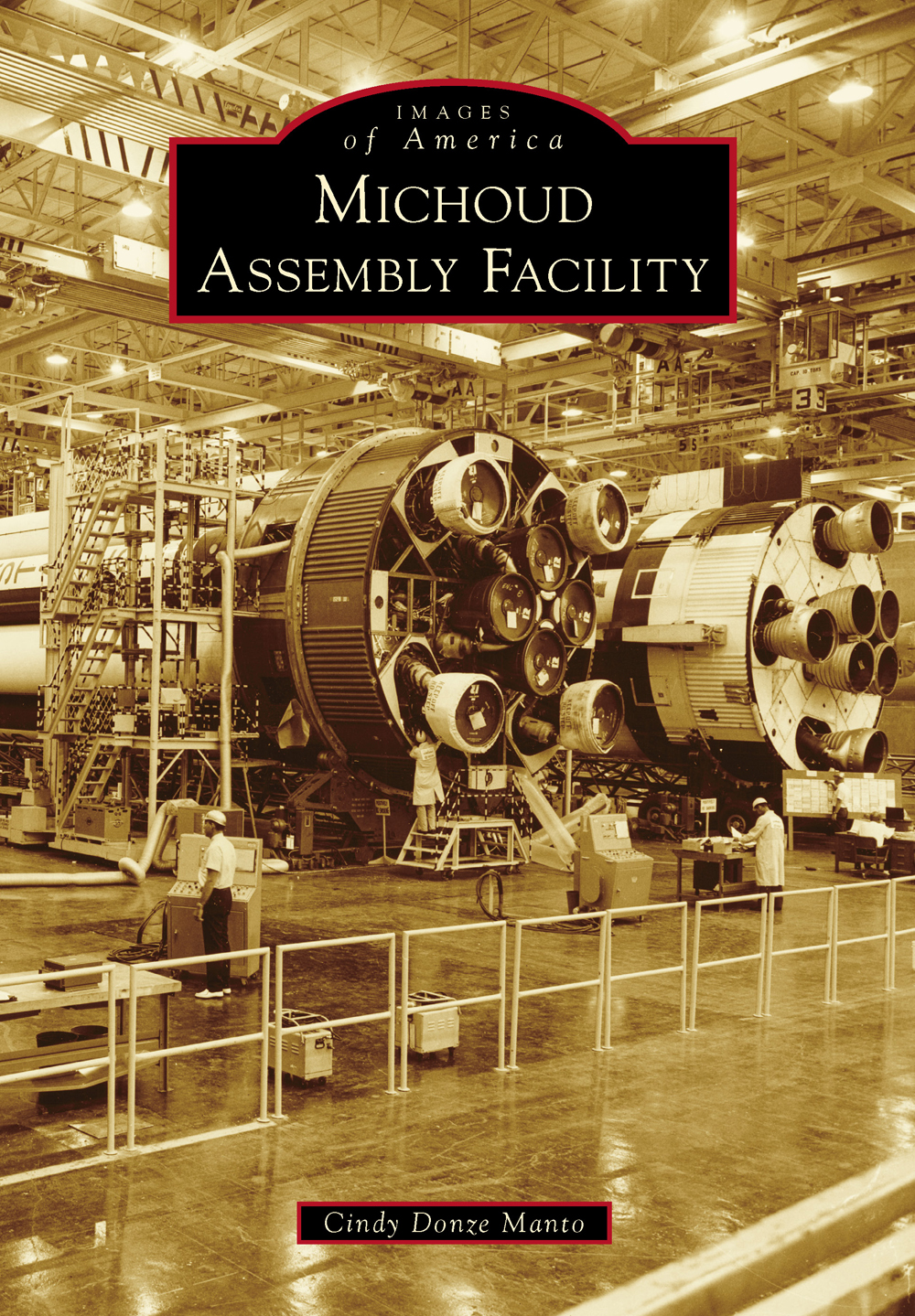

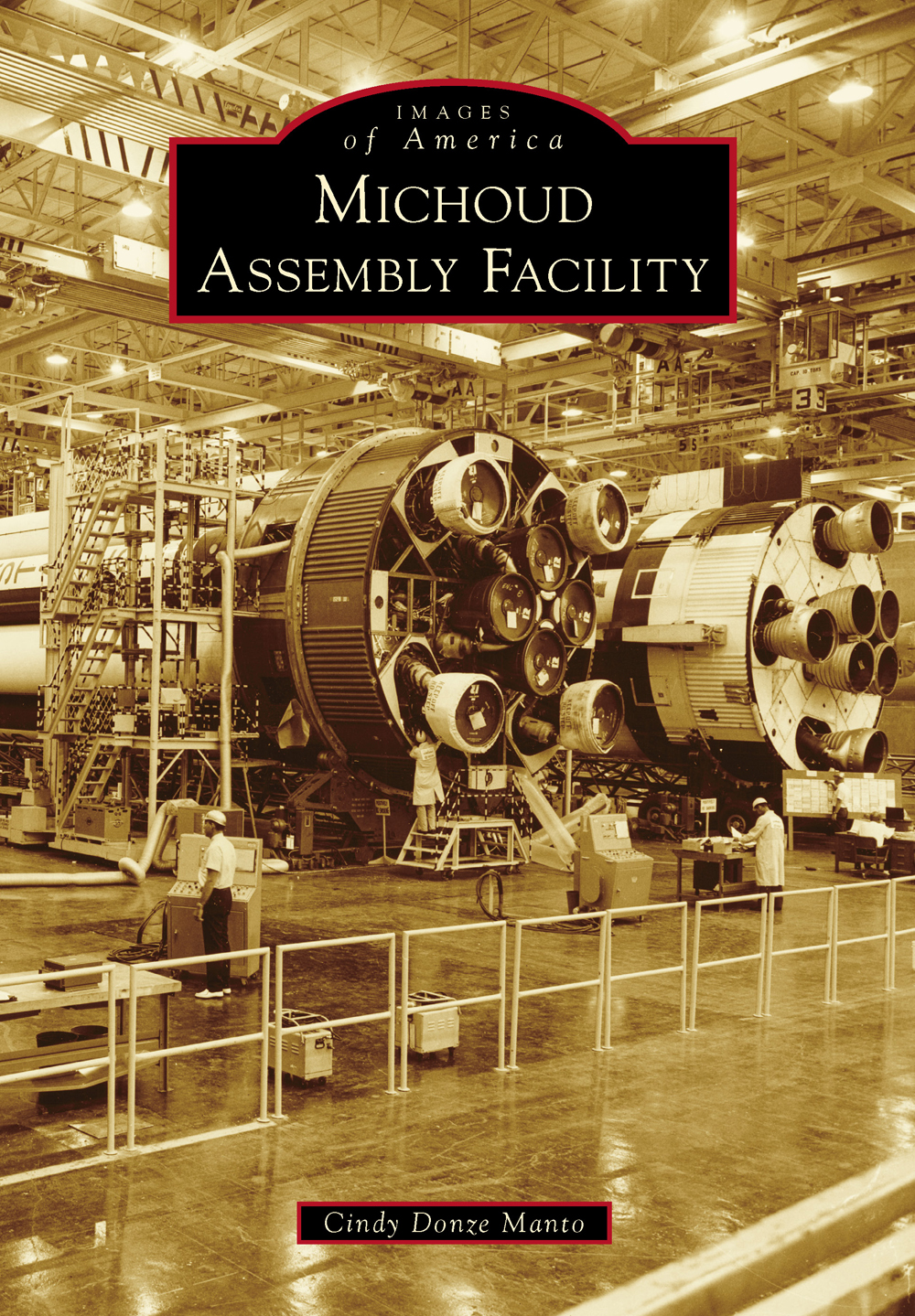

ON THE COVER: Shown on September 8, 1965, in the assembly stage are three of the twelve Saturn IB booster rockets being built by the Chrysler Corporation. After assembly, the completed boosters were shipped by barge to the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for static testing and then to Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Cape Canaveral, Florida, for launch. (Courtesy of the National Archives.)

IMAGES

of America

MICHOUD

ASSEMBLY FACILITY

Cindy Donze Manto

Copyright 2014 by Cindy Donze Manto

ISBN 978-1-4671-1213-0

Ebook ISBN 9781439647240

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014944611

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my husband, Fulvio Manto, an aerospace and astronautics engineer who immigrated from Italy and began his career at Michoud Assembly Facility.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Irene Wainwright of the New Orleans Public Library, Cathy Miller of the National Archives, Robert Ticknor of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Kevin Kelly of The Boeing Company, Danielle Szostak of Chrysler Historical Services, Anne Coleman of the M. Louis Salmon Library at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Matthew C. Hanson of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, Janice Davis of the Harry S. Truman Library, Kathy Struss of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum, Sean Benjamin of the Louisiana Research Collection of the Howard-Tilton Memorial Library at Tulane University, Carl J. Howat of Jacobs Technology, and Sierra Nevada Corporation. Finally, thanks to Stephen A. Turner, emergency preparedness officer, and Malcolm W. Wood, deputy chief operating officer, both of NASAs Michoud Assembly Facility.

Many thanks to Mike Jetzer, the creator of heroicrelics.org; Jerry E. Strahan, the authority on all matters concerning Andrew Jackson Higgins; Robert B. Newton, a native of Great Britain, whose stories and engineering experience at Michoud began with Apollo and extended to the Space Shuttle era; and to Mary Ann Dutton, who moved to New Orleans for the External Tank and whose long friendship provided an insightful perspective into the shuttle era at Michoud. Thanks also to Kenneth J. Donze for his expertise in automobiles.

Please note that this is not an official publication of Jacobs Technology or NASA and that any opinions expressed or errors in content are the responsibility of the author.

Cindy Donze Manto

Metairie, Louisiana

INTRODUCTION

Todays Michoud Assembly Facility was carved from a land grant to the wealthiest citizen in the Louisiana Territory on March 10, 1763. A successful businessman and commandant of the militia, Gilbert Antoine St. Maxent boldly requested 34,500 acres of land east of New Orleans from King Louis XV of France, along with exclusive trading rights with the local Native American tribes.

This land grant, or patent, was conditioned upon St. Maxents ability to build a plantation on the property, bring a roadway across its width, and reserve all the trees for building or repairing royal ships. The French migr continued to maintain his prominent position five years later, when the dominion came into Spanish possession, by merely changing his name to Gilberto Antonio St. Maxent.

Although the building or repairing of royal ships never occurred, an established plantation, including a road connecting St. Maxents neighbors property with his, to a point called Chef Menteur, was in place at his death in 1796.

The Chef Menteur or Chief Deceiver was and still is a tidal estuary of Lake Borgne and the Gulf of Mexico whose misleading current flows either way with the tide. The Chef Menteur is the largest of several such estuaries in the area (the Rigolets, small streams, is the other). It is a well-known landmark in the southeastern portion of this tract of land, offering entry into the interior of the large peninsula and a shorter route to the city of New Orleans.

During the final years of Spanish colonialism, this great expanse of land was acquired by the singular Lt. Louis Brognier DeClouet in 1796. A descendant of a prominent Creole family from St. Martinville, Louisiana, DeClouet was a militiaman and all-around playboy in New Orleans. Harboring not-so-secret sympathies to Spain, Lieutenant DeClouet basically used his property to pay off gambling debts by selling off small parcels of it over time. Eventually, he sold the remainder of his land to another migr from France and civil engineer for the City of New Orleans, Barthelemy Lafon.

An architect, theatrical promoter, cartographer, builder, appraiser, iron master and foundry owner, publisher, major in the militia, and smuggler incognito with the pirate Jean Lafitte, Lafon purchased the acreage in 1801. There, he continued the production of sugar at his plantation, now known as Lheureuse Folie (Happy Folly). After the Louisiana Territory was sold to the United States in 1804, Lafon immediately sought the legitimate recognition of his land ownership from the new government and proposed the use of the chemin du Chef Menteur, the footpath that ran alongside the Chef Menteur, as a major mail route to Washington, DC, in 1805 for the sum of $3,500. This route would follow the Carondelet Canal out of the city to Gentilly Road, cross at Chef Menteur, and continue eastward into Mississippi and beyond. After demonstrating the convenience of establishing a direct route between New Orleans and Washington, DC, Lafon proposed the sale of the trees from his plantation to the US Navy for shipbuilding in 1812.

Between 1810 and 1815, Lafon surveyed the citys defenses and prepared fortifications on his property prior to the onset of the Battle of New Orleans. He chose the site and designed and built Fort Petite Coquilles (little shells) on the advice of his friend, Jean Lafitte, on the coast of Lake Pontchartrain to the north. However, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson complained that it was of little use protecting the Chef Menteur Pass between Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Catherine.

As the War of 1812 was about to end, continued reports of British troops circulating about the American Louisiana territory were becoming closer to reality when a British landing party was reportedly sighted at the Chef Menteur on Lafons Happy Folly plantation on Christmas Day, 1814. Although the report proved to be false, General Jackson, for whom the British were constant enemies, ordered the chemin du Chef Menteur or Chef Menteur Road, fortified for military use should the British return upon the Plains of Gentilly and to serve as easy access into New Orleans. The British seizure of New Orleans could easily lead to an invasion of the United States proper from the south.

After the Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, at the village of Chalmette, less than 10 miles from the French Quarter, General Jackson ordered a redoubt at the confluence of Chef Menteur and Bayou Sauvage and completed and stationed a contingent of 450 free black troops there until he was certain that the British had left the coast.

Next page