Copyright 1995 by George G. Blackburn

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Blackburn, George G.

The guns of Normandy : a soldiers eye view, France 1944

eISBN: 978-1-55199-462-8

1. Blackburn, George G. 2. World War, 19391945 Personal narratives, Canadian. 3. World War, 19391945 Artillery operation, Canadian. 4. World War, 19391945 Campaigns Normandy. 5. Canada. Canadian Army History World War, 19391945. I. Title.

D 811. B 53 1995 940.542142 C 959320377

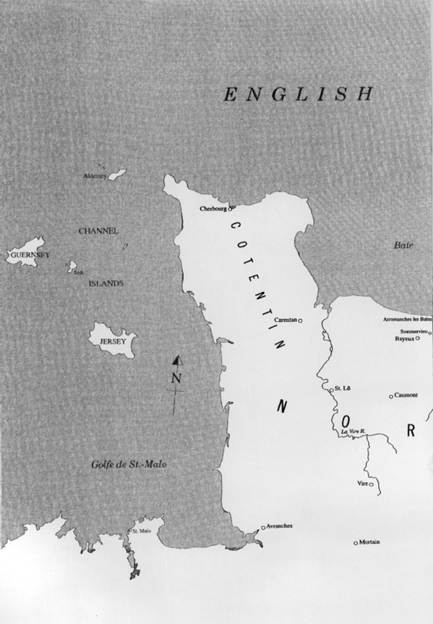

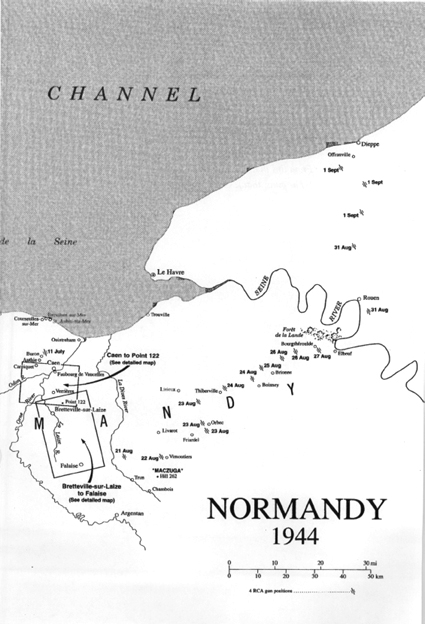

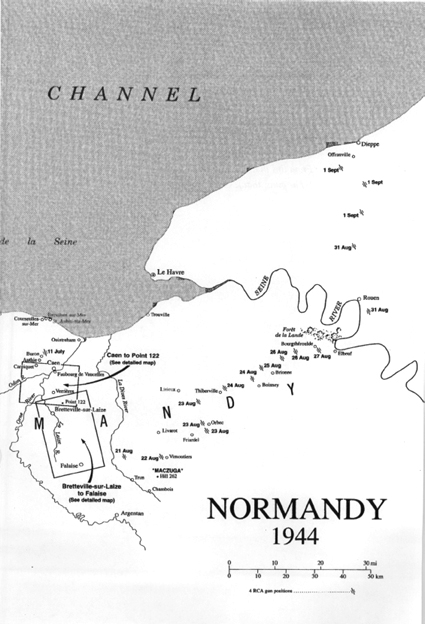

Maps by William Constable

The publishers acknowledge the support of the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council for their publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Inc.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P 9

v3.1

Dedicated to all who served in Normandy, and to all who loved them and lived for months on end in dreadful suspense, particularly mothers and wives who, like my dear Grace, never knew when the doorbell rang that there wouldnt be a telegram beginning We regret to inform you.

Ubique means that warnin grunt

The perished linesman knows,

When oer his strung and sufferin front

The shrapnel sprays his foes,

And when the firin dies away

The husky whisper runs

From lips that havent drunk all day

The guns, thank God, the guns.

Rudyard Kipling

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THIS WAS TO BE SIMPLY THE STORY OF ONE REGIMENT OF 25-pounders in Normandy engaged in what may have been the most intense clash of arms on any front in World War II, written in such a way as to allow our grandchildren to relive those awful days when the fate of Europe and the course of history, as it concerns the thrust of democracy across this earth, hung in the balance.

However, to make understandable the crucial role of the guns and the awesome concentrations they were called upon to fire day after day, rising to insane levels along Verrires Ridge south of Caen in late July, it has been necessary to describe in some detail the terrible problems confronting the frontline troops and the artillery forward observation officers ( FOO s) and crews who shared their lot in every attack and counter-attack.

And since no one can properly appreciate the valour and judge the effectiveness of the frontline soldiers, and the gunners who supported them, who does not fully appreciate the unparalleled severity of the fighting in Normandy, an earnest effort has been made to capture the high tension overlaying every minute of every hour of every day for weeks on end, when massive opposing forces were committed to endless offensive operations designed to overwhelm and destroy each other in a bloodbath that was pursued with unabated fury for almost three months, with neither side allowed any flexibility of manoeuvre the Allies confined by the perimeters of the bridgehead, and the enemy denied any planned withdrawal by their Fhrer.

However, locating material describing what it was like at the cutting edge of 1st Canadian Army from the middle of July until the end of August in effect the fighting from Caen to Falaise that entrapped the German armies in Normandy was very difficult. No one has succeeded in accurately describing the ferocity of the battles for Verrires Ridge and beyond. And perhaps no one ever will, for few who served with the rifle companies of the infantry battalions, including artillery FOO s and their crews, managed to survive more than a few days.

Some were casualties within hours of joining units, and, of the few who survived to see it through all the way with a rifle company, none seemingly have been able or willing to write of it. During my interviews with them many of which were conducted right after the war ended, when battle experiences should still have been alive and clear I discovered that for those who had survived the worst of it, memories of Normandy were blurred and disordered bits and pieces. While retaining vivid impressions, they recalled few details and resorted to generalities when they tried to describe them.

Over and over I heard, gawdawful terrifying completely demoralizing bloody hell scared shitless, and other combinations of four-letter words favoured by soldiers, but when pressed for details their responses were embarrassingly sparse.

And beyond having no recall of what happened from hour to hour for days on end, some could not even remember having been in an attack where I personally knew they had been. This I found difficult to believe until I tried filling in diary notes of my own memories of later battles in the Rhineland and found myself lost in the same impenetrable fog, unable to account for more than a few hours of the days I had been involved, and what little I could recall had the quality of a nightmare.

Obviously the same combination of exhaustion and terror that makes it difficult to think or see clearly in the shattering confusion and roar of battle (when a man functions only from habit, drill, and discipline), makes it equally difficult to retain coherent, detailed memories, in much the same way the conscious mind is able to recall only a few disconnected details and a general impression of horror on waking up from a nightmare. And so I could only piece together a composite picture, made up of the fragmentary memories of some who survived in humble thankfulness those awful days, and place these back to back with the frightful casualty statistics.

The official record-keepers of those times were of no help; they seem to have been entirely disinterested in recording such matters. Beyond brief references to the weather, there is little recognition of the conditions under which the fighting soldier existed, which, more often than not, were dreadful. While extremely useful in authenticating personal notes and diaries, none of the sparse unit diaries or post-battle intelligence reports make any serious attempt to describe what was entailed in simply staying alive during those terrible days and nights.

This deficiency in the material set down at the time by those responsible for preserving historical records (on which all official and unofficial histories would be based) has led to inaccurate, irresponsible conclusions bordering on outright dishonesty even in the works of our own official historians regarding the training and fighting qualities of Canadian officers and men in World War II. And these inaccuracies insulting to the memory of all those Canadians who died facing the enemy while the official record-keepers sheltered miles to the rear are being perpetuated by British and American writers and even built upon by some domestic revisionists.