Acknowledgments

The subtitle of this book mirrors its theme: How Ordinary Allied Soldiers Defeated Hitler. It is the thoughts and deeds of these warriors of Normandy that we now present. They were far from ordinary, these young soldiers and airmen; they gave up their youth and lives to fight for freedom. Scores of these veterans of six nations were generous in sharing with us their personal experiences, their diaries, letters, and photographs, giving us unconditional permission to use them. The many references in our endnotes at the back of this book to these interviews and personal archives are a reflection of their value. We are very grateful for the confidence and support of these men. The authors take full responsibility for any errors or omissions.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council. We thank the National Archives, the National Archives of Canada, the Public Record Office in the UK, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Royal Canadian Military Institute, the Eisenhower Center for American Studies (Metropolitan College, University of New Orleans), and the Laurier Centre for Military Strategic and Disarmament Studies, for their generous permissions for the use of their documents and photographs.

We especially single out the historians of the Laurier Centre, Mike Bechthold, John Maker, and Karen Priestman, the indexer of this book, for their invaluable research, guidance, and assistance.

We walked the battlefields of Normandy with much help and encouragement. Of great valueand funwere the days we spent clambering over battle sites with the fine young scholarship students of the Canadian Battlefields Foundation. For each of the past ten years the Foundation has awarded scholarships to twelve senior university students for two intensive weeks studying the battle sites of the wars of the twentieth century.

We had a fascinating day reliving the St. Lambert battle through the eyes of men who grew up in that area, assembled and coordinated with the help of a scholar of the battle, Colonel Jacques van Dijke of Rotterdam. We thank Ms. Pierre Grandvalet, Fank, Margerie, Madeleine, Huille, and Masson for their tmoinages and hospitality.

In Argentan we met M. Poulain; in Chambois, M. Chambart; in Thury Harcourt, Abb Launay (formerly padre of Tournai-sur-Dives); in Falaise, M. Digueres and M. James; in Mortain, M. Langlois and M. Buis-son; in Paris, M. Eddy Florintin.

Our research on the Polish military was greatly assisted by Krzysztof (Chris) Szydlowski, vice president of the 1st Polish Armoured Association of Canada, who introduced us to veterans of those days; and by Alicja Al-tenberger, executive editor of The Life of Polonia, a Quarterly Publication of the Polish American Congress of Eastern Massachusetts, Boston.

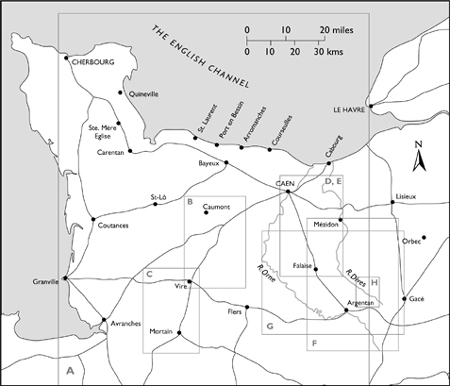

We appreciate the thoughtfulness and professionalism of our agents, Linda McKnight, Westwood Creative Artists of Toronto, and Milly Mar-mur of New York City, and of our editor at Presidio Press, Ron Doering. The excellent maps are the work of Paul Kelly, gecko graphics inc. Kirsten Sheffield created the wonderful portraits of the soldiers of Normandy.

We are grateful to Linda Risacher Copp, Professor Ian Shaw, Bill Baggs, Ken Turnbull, and Martie Whitaker for their critiques and technical advice. During the lengthy process of producing five books of military history, our families have stood by us with unwavering love and understanding. Thank you.

Contents

PART I:

CHAPTER 1:

CHAPTER 2:

CHAPTER 3:

CHAPTER 4:

PART II:

CHAPTER 5:

CHAPTER 6:

CHAPTER 7:

PART III:

CHAPTER 8:

CHAPTER 10:

PART IV:

CHAPTER 11:

CHAPTER 12:

CHAPTER 13:

CHAPTER 14:

CHAPTER 15:

CHAPTER 16:

CHAPTER 17:

CHAPTER 18:

CHAPTER 19:

CHAPTER 20:

CHAPTER 21:

PART V:

CHAPTER 22:

CHAPTER 23:

CHAPTER 24:

CHAPTER 25:

CHAPTER 26:

CHAPTER 27:

CHAPTER 28:

CHAPTER 29:

CHAPTER 30:

CHAPTER 32:

CHAPTER 33:

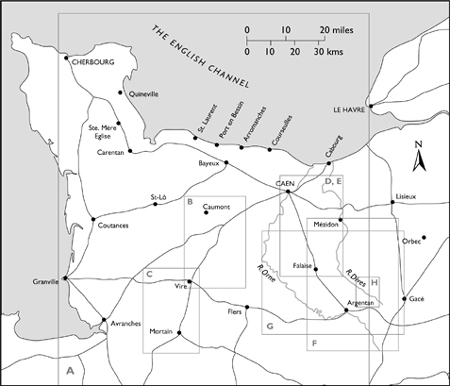

Normandy Key Maps

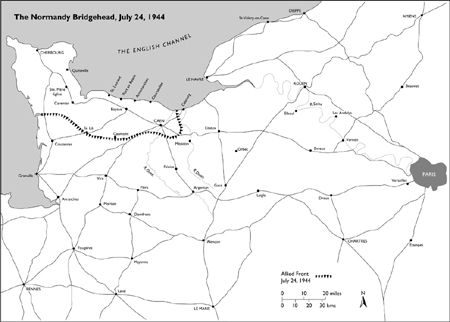

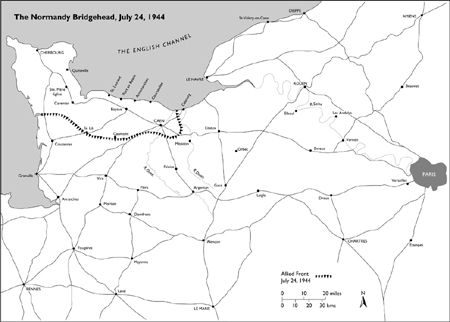

The Normandy Bridgehead,

July 24, 1944

(map on page xiv-xv)

Breakout in the Bocage

(map on page 80)

British Breakout:

Operation Bluecoat

(map on page 92)

Mortain Counter-Attack

(map on page 110)

Operation Totalize

(map on page 134)

Operation Tractable

(map on page 182)

Trun-Chambois Gap:

August 18 (map on page 226)

Victory in Normandy

(map on pages 25859)

Closing the Gap:

August 21 (map on page 290)

Preface

Helping to research a book when one of the authors is an authentic war hero and the other an experienced journalist and writer is a sobering experience for an academic historian. Denis Whitaker led one of the most consistently effective battalions in the Allied armies and won two DSOs [Distinguished Service Orders] in close combat with the enemy.

A soldier's soldier, he knew battle from the sharp end and from the planner's perspective. Denis was always ready to question official explanations, especially when offered by generals or historians who lacked direct experience of combat.

The limitations of allied armor, the strength of German reverse slope defenses, the problems of combat in bocagelike country were all challenges that he had met and mastered on the battlefield.

Denis's skepticism was reinforced by his wife Shelagh's training and instincts as a journalist. Shelagh wanted clear, comprehensible answers to basic questions. The writer's job, she argued, was to clarify issuesnot to add complexity and confusion.

As we collaborated on our research of the Normandy campaign, two factors became paramount: It was the soldiers who won the battle, and it was their commanders who very nearly lost it.

The land troops and the supporting airmen destroyed two large, well-equipped German armies in just seventy-six days. They accomplished this despite faulty leadership, inferior equipment, and bad command decisions.

The allied armies were commanded by men whose inflated reputations are hard to understand. Montgomery may have been the master of the set-piece battle, but after the American breakout at St. L he proved unable to manage a fluid battle. His failure to reinforce the Canadians on the north side of the Falaise Pocket, or to order the Americans to close from the south allowed tens of thousands of enemy soldiers to escape to fight another day.

Montgomery was not the only one to endanger the soldiers victory in Normandy. Eisenhower's passive behavior throughout the campaign suggests that he had not yet acquired the attributes of a great commander. Bradley's role in stopping Patton at Argentan and failing to insist that his aggressive army commander keep enough divisions in position to close the trap raises serious questions about his qualifications to command an army group in 1944.