Poem formatting, including line breaks, stanza breaks etc, may change according to reading device and font size. For this reason The Gallery Press encourages readers to calibrate their settings in order to achieve optimal viewing. This will ensure the most accurate reproduction of the layout of the text as intended by the author.

1

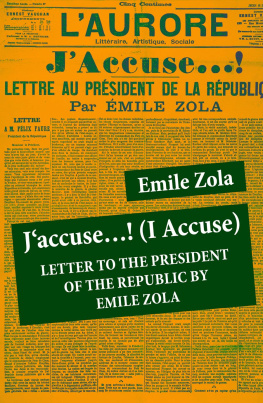

There are many enigmas surrounding the life and work of Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), not least in the matter of the background, origin and composition of the

Illuminations, a possibly unfinished collection of forty prose poems and two in free verse. The manuscripts, so far as we know, are undated, without any indication as to how the poems should be ordered; but it is generally thought that they were written sporadically between 1872 and 1875, in various locations, including Paris, London and Belgium, and that some of them may (or may not) constitute Rimbauds last poetic work. What we do know is that the manuscripts were once in the possession of Rimbauds erstwhile lover, the poet Paul Verlaine, and that the majority of the poems were first published in 1886 by the Symbolist review

La Vogue, which referred to their author as the late Arthur Rimbaud and the equivocal and glorious deceased.

It seems Verlaine had written to Rimbaud, then in Africa; receiving no reply, he assumed he was dead. Later in 1886 La Vogue published the Illuminations in volume form, with a preface by Verlaine in which he explained: Le mot Illuminations est anglais et veut dire gravures colores coloured plates, though it is unclear whether Rimbaud himself chose the title. If he did, it might conform to his eccentric or playful use of English titles for the poems Being Beauteous, Bottom and Fairy, for Illuminations is not, as Verlaine states, an English word meaning coloured plates. The only definition for illumination in the Oxford English Dictionary which resembles Verlaines is formerly, also, the colouring of maps or prints, as in 1678 E. Phillips New Worldof Words (ed. 4), a laying of colours upon Maps or Printed Pictures; so as to give the greater light, as it were, and beauty to them.

This is not quite illumination in the English sense of decorating letters in a text (enluminure in French), which might lie at the back of Verlaines coloured plates; but illuminations can also be a show of festive lights, or, appropriately for Rimbaud, divine or poetic inspiration. In his famous lettre du voyant, Rimbaud declared: One must, I say, be a seer, make oneself a seer. The poet makes himself a seer through a long, prodigious and rational disordering of all the senses. However we gloss the title Illuminations, the poems flit within the inward eye like brightly-coloured magic lantern slides, pictures from a marvellous book, visions of another world, scenes from an avant-garde film. Rimbaud was avant-garde before the Avant-garde; a surrealist before Surrealism; and, environmentalist avant la lettre, his critique of industrial society in some of these poems is still relevant today.

2

In 1998 I published

The AlexandrinePlan, translations or adaptations of sonnets by Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Mallarm.

2

In 1998 I published

The AlexandrinePlan, translations or adaptations of sonnets by Rimbaud, Baudelaire and Mallarm.

My concern in that book was not so much to give a literal meaning of what the poems might be saying, as to reproduce the original metre in English, and see what interpretations might emerge from those constraints, both of rhyme and the twelve syllables of the classical French alexandrine. Shortly afterwards I thought I might attempt a translation of some of the poems in Illuminations; but, try as I might, I could not arrive at any form of words that did justice to the originals, to my understanding of what they might imply or mean, or to my sense of their music. What I did seemed inert, flabby, prosaic, and too close to whatever English translations I had consulted to augment my passable French. I could find no edge to the matter. I retired defeated and forgot about the whole brief affair. Then, on 3 April 2012 (Shrove Tuesday, as it happened), I received an email from Colin Graham of the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, asking if I might be interested in doing versions of seven of the prose poems from Illuminations, which would then be worked on by graphic designers for an exhibition in the new Illuminations gallery at Maynooth.

I had not done any kind of poetry for some time, and the invitation seemed serendipitous. On Spy Wednesday I had a kind of illumination of my own: rather than translate the prose poems as prose poems, I could perhaps adapt them to an Alexandrine format of twelve-syllable rhyming couplets Rimbaud crossed with Racine, as it were. I set to the next day, Holy Thursday, and somehow within a week I had arrived at twenty-two such versions. I spent the next few weeks tweaking and tinkering, and added three prose versions to frame what had now become a book: not the book that is Rimbauds Illuminations, but another, taken from that book. At first, it seemed perverse to translate prose poems into verse: but the more I worked the more it became apparent that many passages in Rimbauds musical prose could be read as verse, with a prosody of their own, scanned, rhymed, alliterated. One could see incipient sonnets embedded therein; and it happened that several of my versions came out as fourteen lines.

So I began to think of the project as a restoration, or renovation, rather than a complete makeover. In any event these versions are not conventional translations. The constraints of rhyme and metre led me to cut, interpolate, and interpret. There are instances where I have added to or taken away from the original. I have sometimes twisted Rimbauds words. And Rimbauds words, of course, twisted mine.

Examining his French, I had also to examine my English, learning other aspects of it, sometimes relearning it, for one can never fully know a language, which is always bigger than any of us. As Walter Benjamin has it in The Task of the Translator (one of a number of essays collected under the English title Illuminations), [The translator] must expand and deepen his language by means of the foreign language. Ones own language begins to seem another. So in translation one necessarily becomes Another. First-person , third-person, noun and verb, become confused: Je est un autre, I is another, as Rimbaud has it. I began by wanting to obey the constraints of the twelve syllables of the alexandrine, but that proved impossible: the line, under the pressure of Rimbauds sometimes elaborate and often elliptical syntax, began to lengthen or contract in places, and thus became even more hybrid than what I had envisaged.

I was not too put out by this failure to abide by my own rule: the prose poems seemed to want that variation of pace and rhythm; written in different voices, different keys as it were, they vary considerably in their linguistic strategies. The strain of the verse form grafted on to Rimbauds prose led to hybrid: translation as mutation. Having said all that, I have translated as closely to my understanding of the original as I could, when I could. The result of my deliberations follows. Or rather, it has gone before, since this Authors Note, like all such introductions, has been written after the event.

Once more the lighting returns to the central beam, the rooftree .

From the two far ends of the room nondescript stage sets harmonic elevations merge or mingle. The wall facing the spectator is a