Baudelaire Rimbaud Verlaine SELECTED VERSE AND PROSE POEMS  BAUDELAIRE

BAUDELAIRE

RIMBAUD

VERLAINE Selected Verse and Prose Poems EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY Joseph M. Bernstein A CITADEL PRESS BOOK Published by Carol Publishing Group Acknowledgements This collection is made possible by the generous prermissions extendedby the holders of copyright listed below. ALBERT BONI. The Arthur Symons translations of FLOWERS OF EVIL and Prose Poems by Charles Baudelaire. GERTRUDE HALL. The Gertrude Hall translations of Selected Verse by Paul Verlaine.

EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY Joseph M. Bernstein A CITADEL PRESS BOOK Published by Carol Publishing Group Acknowledgements This collection is made possible by the generous prermissions extendedby the holders of copyright listed below. ALBERT BONI. The Arthur Symons translations of FLOWERS OF EVIL and Prose Poems by Charles Baudelaire. GERTRUDE HALL. The Gertrude Hall translations of Selected Verse by Paul Verlaine.

THE HOGARTH PRESS. LONDON. The J. Norman Cameron translation of Illuminations by Arthur Rimbaud. NEW DIRECTIONS. The Louise Varse translations of A Season in Hell and Prose Poems from Illuminations by Arthur Rimbaud.

SAMUEL ROTH. The Arthur Symons translation of poems from In Parallel Fashion by Paul Verlaine. Carol Publishing Group Edition - 1993 Copyright MCMXLVII, MCMLXXV by The Citadel Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review. A Citadel Press Book Published by Carol Publishing Group Citadel Press is a registered trademark of Carol Communications, Inc. Editorial Offices: 600 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10022 Sales & Distribution Offices: 120 Enterprise Avenue, Secaucus, NJ 07094 In Canada: Canadian Manda Group, P.O.

Box 920, Station U, Toronto, Ontario. M8Z 5P9, Canada Queries regarding rights and permissions should be addressed to: Carol Publishing Group, 600 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10022 ISBN 0-8065-0196-0 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 Carol Publishing Group books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases, for sales promotions, fund raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details contact: Special Sales Department, Carol Publishing Group, 120 Enterprise Ave., Secaucus, NJ 07094 Contents Introduction I IF WE WERE TO ASK AN ENGLISHMAN to name the single greatest poet in English literature, his answer would unquestionably be: Shakespeare. Similarly, a German upon questioning would reply: Goethe; an Italian, Dante. And an American could surely make a good case for Walt Whitman.

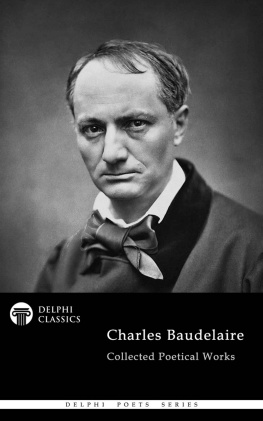

These men are more than national poetsthey are universal figures, expressing the genius of their age, their country, their language, and their culture. But who is the greatest poet in French literature? Here we get a variety of answers, for there is no one French poet who towers so high above his fellows as to leave no doubt about his unique preeminence. There are many great French poets: Franois Villon, Pierre Ronsard, Jean Racine, Alfred de Vigny, Victor Hugo, to cite but a few across the centuries. Some years ago the contemporary French writer, Andr Gide, was asked who, in his opinion, was the outstanding poet of France. He answered: Victor Hugo, alas! Admiring the powerful sweep and indefatigable eloquence of Victor Hugo, the sonorous echo of the 19th century in prose and verse, we cannot share Gides precious aesthetic dismay. Nevertheless, we have in mind not Hugo but one of his contemporaries, Charles Baudelaire, as our candidate for the first poet in the republic of French letters.

Increasingly of late, lovers of literature have come to recognize the true stature of Baudelaire. In the eighty years since his death, his reputation both in France and abroad has grown apace. His life spanned the years 1821 to 1867; yet he is strikingly modern in every sense of the term. Stendhal, the French novelist, predicted around 1830 that his novels would be understood in fifty years; and as he had foretold, his fame grew after 1880. In the case of Baudelaire, no such prediction was forthcoming; yet it is a fact that in his own time he was little understood or completely misunderstood. is clothed in cold and sinister beauty, and was created with rage and patience. is clothed in cold and sinister beauty, and was created with rage and patience.

Besides, the proof of its positive value lies in all the evil that has been said of it. The book infuriates people.... People refuse me everything: power of invention and even a knowledge of French. I despise all those imbeciles, for I know that this volume, with its defects and its qualities, will make its way in the minds of the literary public beside the best work of Victor Hugo, of Thophile Gautier, and even of Byron. In our own day we have begun to make up for the neglect and hostility which Baudelaire suffered among most of his contemporaries. Now it is true that Baudelaire is not a world poet, a summum, in the same sense as Shakespeare, Dante, or Goethe.

He is not on their lofty, all-encompassing level, out-topping knowledge. To assert that would be to push ones admiration to the edge of idolatry. Yet as a poet of love, a master in depth, a craftsman in the sensuous and the sensual, a devotee of the Cult of Beauty, a practitioner in what has been aptly called the Alchemy of the Word, an inexorable self-analyst and explorer of the sub-conscious in poetry, a creator of images that fire the senses, quicken the heart, and illumine the mind, Baudelaire has few if any peers in the entire roll-call of modern poets. Not to know him is to deprive oneself of a pleasure as rare as it is indispensable to any real understanding of the aims and direction of modern literature. Wherein lies his greatness? Why do we insist on stressing his modernity, his direct and unusually vibrant appeal to modern man? There are many reasons: here let us state the most important ones. In the first half of the 19th century, the leading poets of Europe were Romantics.

Romanticism placed emphasis on sentimentality and wayward inspiration, on meetings in the moonlight, disappointed love, solitary walks in the woods, and nostalgic trysts by the shores of lonely lakes. There was in the poems of Romanticism a certain softness, a tendency to histrionics, self-pity, self-dramatization, and emotional over-indulgence. As a result, rhetoric was often substituted for emotional truth, tearfulness for tragedy. The idea of escape, escape either in time or spaceanywhere out of the worldprevailed. Baudelaire, whose Flowers of Evil appeared in 1857, travelled a different road from these practitioners of Romanticism. Where they sentimentalized, he was disciplined, rigorous, and astringent in his self-analysis.

Where they dissolved into soft, loose, vaporous tears, he cut through to the hard core of thingsthe tragic sense of life, which great artists of all times have expressed. All through his Flowers of Evil, his prose-poems, and his Intimate Journals, this constant self-scrutiny and self-dissection have a modern ring. They throw light on the central problem of the artist in our time. At one point in his diaries, for example, Baudelaire confesses his purpose: To be a great man and a saint every day for oneself. On another occasion he invokes the aid of souls of those I have loved, souls of those I have sung, fortify me, sustain me, banish from me the lies and obscuring mists of the world; and you, Lord God, grant me the grace to compose a few beautiful verses which will prove to me that I am not the lowliest of men and that I am not inferior to those I despise. In his poem, A Journey to Cytbera, he suddenly cries out at the end: In thine isle, O Venus, I found only upthrust A Calvary symbol whereon mine Image hung.

Give me, Lord God! to look upon that dung, My body and my heart, without disgust! This mixture of love and hate, of attraction and repulsion; this antithesis of the sublime and mean, the radiant and banal; this intermingling and interpenetration of good and evil, heaven and hell, mark Baudelaire out as a

Next page

BAUDELAIRE

BAUDELAIRE EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY Joseph M. Bernstein A CITADEL PRESS BOOK Published by Carol Publishing Group Acknowledgements This collection is made possible by the generous prermissions extendedby the holders of copyright listed below. ALBERT BONI. The Arthur Symons translations of FLOWERS OF EVIL and Prose Poems by Charles Baudelaire. GERTRUDE HALL. The Gertrude Hall translations of Selected Verse by Paul Verlaine.

EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY Joseph M. Bernstein A CITADEL PRESS BOOK Published by Carol Publishing Group Acknowledgements This collection is made possible by the generous prermissions extendedby the holders of copyright listed below. ALBERT BONI. The Arthur Symons translations of FLOWERS OF EVIL and Prose Poems by Charles Baudelaire. GERTRUDE HALL. The Gertrude Hall translations of Selected Verse by Paul Verlaine.