Nicholl Charles - Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91

Here you can read online Nicholl Charles - Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Eland Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91

- Author:

- Publisher:Eland Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In Memory of

Kevin Stratford 194984

Je est un autre

Arthur Rimbaud, Lettre du Voyant

You lose yourself

You reappear

You suddenly find

You got nothing to fear

Bob Dylan, Its Alright Ma

Arthur Rimbaud aged seventeen. Photograph by tienne

Carjat.

The Communard: Rimbaud (second from left) in Paris, May

1871. Photograph by Bruno Braquehais.

Manuscript of Premire Soire, Rimbauds first published

poem.

The tropical traveller: Rimbaud in Java and back in Charleville.

Sketches by Delahaye, c. 187677.

Grand Htel de lUnivers, Aden, in the early twentieth century

and in 1991.

Rimbaud on the terrace of the Grand Hotel, Aden, August

1880. Photograph by Georges Rvoil.

Rimbauds contract with Viannay, Bardey & Co., 10 November

1880.

T his book about Arthur Rimbauds years in Africa was first published nearly a quarter of a century ago. There have been some discoveries since then two new photographs; a few fragments of reminiscence from those who knew him; some further information about the Abyssinian woman who lived with him in Harar and Aden. I have incorporated these findings into this new edition. We learn a little more, but the story will always remain shadowy: he has covered his tracks too well.

There have also been some books on the subject, offering new insights and interpretations. They include studies by Claude Jeancolas, Jean-Jacques Lefrre, Jean-Michel Cornu de Lenclos and others; and a great biography by Graham Robb, which is as illuminating on the African years as it is on the rest of Rimbauds extraordinary life. Details of these can be found in Sources, pp. 37989.

Another new photograph of Rimbaud is included here, though it belongs to an earlier period: it dates from 1871, when he was briefly involved in the uprising of the Paris Commune. This is its first appearance in a book. I am very grateful to its discoverer, Aidan Dun, for sharing it with me.

Certain journeys lie behind this book. They are not its subject this is Rimbauds story: I am only following him but it may be useful to know that I was in Aden in 1991, and in Ethiopia and Djibouti in 1994, and that descriptions and comments relating to those places belong to those particular times. The many people who helped along the way are named in the Acknowledgements, but I must mention here my good friend Ron Orders, who covered every inch of the terrain with me, as cameraman, sound-recordist, director and producer of our film about Rimbaud, No Direction Home (Channel 4, 1994).

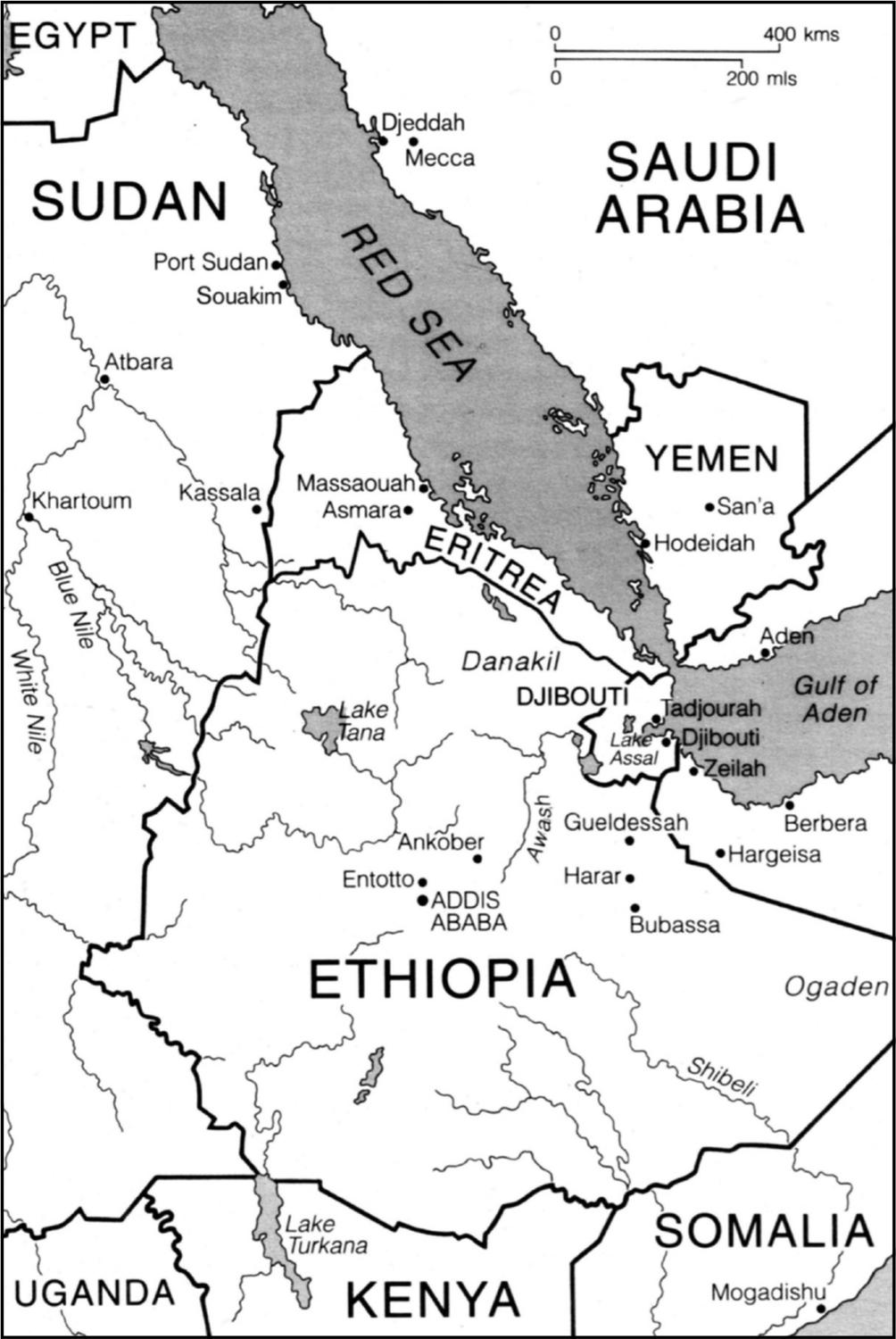

I have regularized the spellings of African place names and ethnic groups, though not on any very scholarly basis, and I have indicated differences of usage between Rimbauds time and ours thus the people he calls Galla are now generally known as the Oromo, the Danakil are Afar, and so on.

All translations from the French are my own. I have of course consulted other translators of Rimbauds poems, for whom see Sources, pp. 37989. Quotations from the poems are given in italics: their presence in the narrative is associative rather than documentary an inner voice from his past. Letters and documents relating to his African years are mostly given here in English for the first time.

Some conversion factors. The chief trading currency in nineteenth-century East Africa was the Maria Theresa thaler, which was then worth about 5 francs; and in Aden the Indian rupee, worth about 3 francs. Other units mentioned in the book are the frasleh (or farasalah), a trade-weight equivalent to about 16 kg; and the daboulah, which is actually a leather pannier for transporting goods by camel, but which was used as a unit in coffee transactions equal to 6 frasleh (100 kg). Two daboulahs constituted a camel load.

I n the year 1880, in the dogdays of August, a young Frenchman disembarks at Steamer Point, in the Arabian port of Aden. He is tall and lean-faced, with chestnut-coloured hair that the sun has faded. His clothes are shabby, his manner brusque. He carries his belongings in a brown leather suitcase fastened with four buckled straps.

He commands attention but is not a curiosity. Aden is a British protectorate, an entrept, a transit-camp for travellers both to Africa and to India. There are plenty of Europeans passing through traders, explorers, engineers, clerks, cooks, all sorts. He might be any of these. He has come, as they mostly do, by steamer through the new Suez Canal, opened in 1869. He has drifted down the Red Sea, short-hauling from coast to coast, looking for any kind of work that was going; and finding none he has come by boat or ship through the straits known as Bab al Mandeb the Gate of Tears and along the desiccated littoral of the Yemen, to Aden.

Much of this may be guessed at a glance. The sunburnt face, the scarred portmanteau: they give that sort of account of him. His eyes might suggest other, less decipherable stories. They are extraordinary: a pale, hypnotic, unsettling blue. Decades later a French missionary who knew him in Africa would say: I remember his large clear eyes. What a gaze!

His eyes are all the more vivid on this particular day because he has a fever. He was very sick up in Hodeidah; he has still not shaken it off.

There are dhows and coal-barges at the wharf, and the shark-fishing boats which are little more than rafts. The eponymous steamers lie off in the glittering water, near the rock called Flint Island, used by the British as a quarantine station. Behind the docks can be seen the principal buildings of the colony: the Governors residence, the Post Office, the agencies of the P & O and Messageries Maritimes shipping-lines, and a scattering of white bungalows, though not yet as numerous as those seen by Evelyn Waugh fifty years later, spilt over the hillside like the litter of picnic-parties after Bank Holiday.

As the boat prepares to dock it is surrounded by children paddling little dug-outs. They are mostly Somali, from the nearby coast of East Africa. They leap and dive and call out for coins: Oh! Oh! Sixpence! la mer, la mer!

A cast-iron jetty leads him to the quayside. The heat is intense: 40 is normal at this time of year. The boats arrival has brought people out from the shade: Somali porters, Yemeni hawkers, sun-ripened English subalterns in scout-master shorts. In the customs shed, under a tin roof, he completes certain formalities.

He dislikes customs men: their pipes clenched between their teeth, their axes and knives, their dogs on the leash.

On the other side there are cabbies waiting, also Somalis, with their little horse-drawn carriages, or gharries, which another French visitor compares to American stagecoaches. His destination is close by; he is heading for the Grand Hotel, one of two French-run hotels in the colony. Its signboard, painted in letters two metres high, is visible from the wharf: GRAND HOTEL DE LUNIVERS. This improbably cosmic name brings a momentary reminiscence of his home town, Charleville, and of a certain Caf de lUnivers up by the railway station, the scene of all those drunken declamatory evenings with Delahaye, with Izambard, with

But their names mean little to him now.

He is heading for the Grand because he has a contact there. Back up the coast, at Hodeidah, laid out with the fever, he was befriended by a French trader, one Trbuchet, an agent for the Marseille company of Morand & Fabre. Trbuchet has friends in Aden, furnishes him with letters of introduction. One is to a certain Colonel Dubar, currently employed in the coffee business. The other is to Jules Suel, the owner of the Grand Hotel.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91»

Look at similar books to Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Somebody Else : Arthur Rimbaud in Africa, 1880-91 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.