Table of Contents

To the memory of

LEONARD MICHAELS

19332003

Come back, come back, dear friend, only friend, come back. I promise to be good.

Rimbaud to Verlaine July 4, 1873

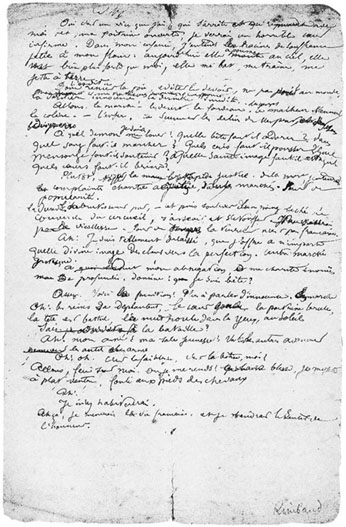

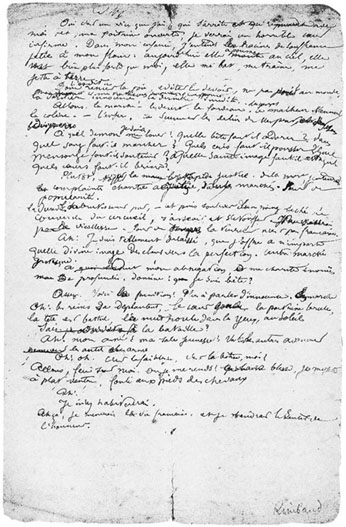

An early draft of Une saison en enfer.

CHRONOLOGY

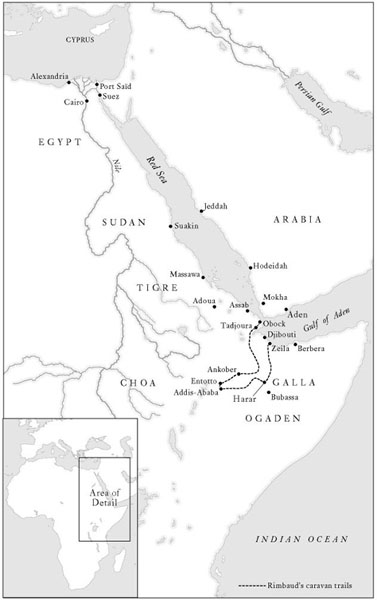

RIMBAUDS YOUTHFUL TERRAIN

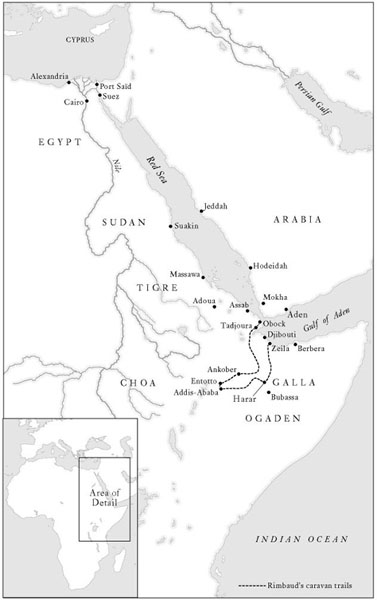

RIMBAUDS ADULT TERRAIN

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Thirty-three of Rimbauds letters have not been included in this edition. Thirty-two were sent to one man, Alfred Ilg, a trading colleague of Rimbauds during the late 1880s. These letters are of interest almost exclusively and certainly exhaustively for their enumeration of goods bought and sold. They are, for the most part, lists or descriptions of merchandise either sent or requested, which, in the editors opinion, is an aspect of Rimbauds commercial existence already more than adequately documented in the following selection. The dates of these letters are listed in an appendix at the back.

INTRODUCTION

I

In the autumn of 1873, Arthur Rimbaud, aged nineteen, arrived at his family home in northeastern France bearing a large bundle. It contained nearly five hundred copies of his longest completed work, a seven-thousand-word prose poem entitled Une saison en enfer. The bundle originated in the Typographical Alliance of M.-J. Poot and Company, Brussels, where Rimbaud had gone to the trouble of having the poem printed in book form. Soon after his return to France, however, he threw the books into the family hearth, incinerating all but a handful of one of the most articulate documents of existential ambivalence in all literature.

This story, confirmed by Rimbauds youngest sister, Isabelle, who witnessed the event, neatly symbolizes one of the most compelling aspects of Rimbauds fame: after revolutionizing French poetry in his teens, he abandoned its pursuit, electing to live the rest of his life in the African desert. A novelist would be hard-pressed to come up with a truer image of artistic ambivalence, or an action that better revealed Rimbauds conflicted character, than that of the poet incinerating the work upon which his posterity now rests. Alas, the one problem with this quintessential moment of truth is that it never happened.

We know that it never happened because of a man named Leon Losseau. Losseau was a lawyer who, on a certain day in 1901, visited the establishment of M.-J. Poot and Company. He was looking not for anything relating to Rimbaud but for a rare judicial publication he suspected might have originated there. The manager, a Monsieur Deghlislage, took Losseau to the attic of the shop. Together they dug through decades of accumulated crates. Losseau, who was also an avid, knowledgeable bibliophile, later explained what happened in a journal for book collectors:

You will understand the emotion a bibliophile felt the instant he saw the contents of a filthy, stained, dusty bundle which, one among many, he had just uncovered. Hundreds of copies of Rimbauds Season in Hell !

Losseau hoarded his discovery for nearly a decade, quietly allowing it to increase in value. When word of the find finally got out, one man was particularly upset by the news: Paterne Berrichon, the writer most responsible for disseminating the tale of A Season in Hell s destruction.

Berrichon was the posthumous brother-in-law of Arthur Rimbaud, having married Isabelle in 1897, the same year he published his first biography of the poet (he published a second in 1912). In his official capacity as literary executor, Berrichon contacted Losseau to confirm the discovery. The biographer then made a shocking request: He asked Losseau to destroy the rediscovered edition to give the appearance of truth to his invention of the destruction.

The temptation is to think of Berrichon as simply a scoundrel, bent on nothing less than the destruction of the truth for the sake of a memorable scene. But within his fictional auto-da-f, the ashes of a truth were buried. Once, in a letter, Rimbaud had asked a friend to burn all the poems I was dumb enough to send you. Berrichon had been the first to publish the letter, in a 1912 issue of La Nouvelle Revue franaise. Perhaps he elected, in complicity with his wife, to fill a narrative gap in Rimbauds lifethe fate of all those missing copies of A Season in Hellwith a scene in keeping with Rimbauds prior behavior. Whatever his ultimate reason, in the service of trying to tell the poets story, of trying to have it make sense, Berrichon made an assumption. And, if we are feeling charitable, a not altogether unreasonable one.

II

The history of Rimbaud biography is one of not altogether unreasonable assumptions. In the hundred years since Berrichons first biography appeared, dozens of authors have tried to tell Rimbauds story. Between 1997 and 2001, four biographical studiesof varying length and ambition but all aimed at the general publicwere published in English. Two were already in print. A seventh and eighth have just appeared in France, arguably making Rimbaud the most written-about literary figure of the past decade.

This bounty is suspicious, for although new dribbles of information appear from time to time, the facts we have about Rimbauds life have remained largely unchanged since Berrichons time. What continues to change is our idea of Rimbaud, and these ideas have often been forged out of so much nothing.

There are countless scenes in the Rimbaud myth that, like the burning of A Season in Hell, seem to offer too telling a detail. Of a poet famous for proclaiming himself a seer, biographers have claimed that he was actually born with his eyes wide open; of a poet famous for fleeing Europe, some claim he was born literally crawling for the door. Because in his teens Rimbaud indisputably had at least one homosexual relationship, he has been portrayed as indisputably gay, despite the absence of any evidence of homosexual liaisons during his adulthood and the clear suggestion of a relationship with a woman. And because a letter dating from his years in Africa mentions his needing two boy slaves, he has been called a slave trader (despite any shred of corroborating fact). Yet how infrequently a bibliophile appears out of the French countryside to set the record straight.

Next page