Front cover: Borobudur

Opposite: Village in Java, from Le Tour du Monde, 1879

Picture credits:

Authors collection 3, 34, 68, 90, 97, 112, 119, colour insert (v, vi)

Photographs courtesy of Jamie James 77, colour insert (iv top)

Editions Didier Millet (Publishers collection) 51, 83, colour insert (ii, viii)

Collection of Olivier Johannes Raap colour insert (iii top)

Courtesy of KITLV/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean

Studies front cover, colour insert (i, iii bottom)

Courtesy of Muse Rimbaud, Ville de Charleville-Mzires 60

INMAGINE 10, 85, colour insert (iv bottom)

Courtesy of ADAGP/Collection Centre Pompidou, Dist. RMN/Jacques Faujour 18

Membership Purchase Fund, photograph courtesy of the Herbert F. Johnson

Museum of Art, Cornell University colour insert (vii)

CONTENTS

for Agns Montenay and Richard Overstreet

T he year 1876 was the pivot of Arthur Rimbauds life, the midpoint between his intellectual beginning as a child wonder in classical languages and his death in 1891, at the age of thirty-seven . Five years before, the visionary verse of the adolescent Rimbaud had astounded literary Paris, which made him its difficult darling; five years later he was a commercial agent in the remote outpost of Harar, Abyssinia, dealing in gold, ivory, and guns, having abandoned literature completely.

In 1873, after the disastrous conclusion of a demented love affair with an older man, the poet Paul Verlaine, Rimbaud embarked on a restless period of foreign travel, which reached its most distant point in the island of Java. In May 1876 Rimbaud enlisted as a mercenary in the Dutch Colonial Army and sailed to the Indies. Soon after he arrived at his garrison in central Java he deserted and vanished into the jungle. Nothing is known of his whereabouts from then until he turned up again in France at the end of the year.

This book is a study of Rimbauds journey to Java. I have called it his lost voyage because we know less about it than any other major passage in his life. From the age of fifteen Rimbaud was a great letter-writer, his correspondence occupying hundreds of pages in his collected works; yet not one letter from 1876 survives. By then he habitually concealed his previous life as a poet from strangers, so to the other men in his battalion he was simply young Rimbaud from Charleville, in the Ardennes, clever and good-looking but nobody special. None of his comrades published a memoir about him. Apart from a handful of terse, opaque official documents relating to his enlistment and desertion, the Java voyage is a void. It remains one of the most elusive enigmas among the many that constitute his tumultuous life, and is often overlooked outside Rimbaldian circles.

There are thousands of people (we know who we are) who would take a lively interest if a pair of socks turned up in an old chest in Harar that could be proved to have belonged to Arthur Rimbaud. For them, for us, an attempt to arrive as close as documentary resources permit at an understanding of Rimbauds adventure in Java requires no justification. Few poets in any language have attracted so passionate a worldwide following in the derisive vernacular, a cult. When a previously unknown photograph of Rimbaud in Aden came to light in 2010, bringing the number of authenticated images of him as an adult to three, it was a major international news story.

The fascination begins in his beautiful, sometimes bewildering poetry, written before he turned twenty. Rimbaud is one of those writers who can change the readers life not in the sense of being an inspiration or a moral guide but by changing the way one thinks. In A Season in Hell, Rimbaud described his growth as a poet:

Poetic antiques played a large part in my alchemy of the word. I became accustomed to pure hallucination: I saw very clearly a mosque in the place of a factory, a school of drummers led by angels, carriages on the highways of the sky, a drawing-room at the bottom of a lake; monsters, mysteries; the poster for a vaudeville show raised horrors before me. Then I explained my magic sophisms with the hallucination of words.

In an era when the word is in retreat, Rimbauds verbal alchemy still has the marvellous power to transport the reader to places that dont exist in this world. This transformative magic required the creation of a wholly original poetic language, one that often defies conventional logic. Rimbauds poetry isnt really an artistic expression so much as an experiment in a new way of thinking. Elsewhere in A Season in Hell he explained, I wrote silences, I wrote the night. I recorded the inexpressible. I made vertigo a permanent state. His virtuosic verse and dazzling prose poems still puzzle readers 140 years after they were written perhaps even more than they puzzled his contemporaries, for most modern readers have lost the habit of reading poetry.

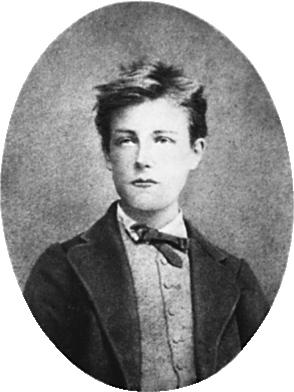

Rimbauds imperishable glamour, in the Scots sense of a spell of enchantment, derives equally from his amazing life, his many lives, a chronicle of adventure, pride, courage and tragedy that defies synopsis. It has the power and suggestive ambiguity of myth. In tienne Carjats iconic portrait of the genius as a schoolboy, his otherworldly gaze simultaneously pours out sweetness and danger. We feel that we know him and that he is unlike anyone we know.

Rimbaud at seventeen, photograph by tienne Carjat, 1871

Reader, beware: the Rimbaud fascination can lead to a consuming enthusiasm, which brings with it the need to spread the word. Henry Miller wrote a study of Rimbaud called The Time of the Assassins, taking his title from the last line of Rimbauds prose poem Morning of Drunkenness (itself a reference to the medieval Persian order of Assassins, the legendary Hashishin). Miller described his response to his first contact with the poetry of Rimbaud: His presence was always with me. It was a disturbing presence, too. Some day you will have to come to grips with me. Thats what his voice kept repeating in my ears.

Rimbaud inspired great artists: T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound acknowledged him as a master; Thomas Mann wrote him letters forty years after his death. Benjamin Britten composed a haunting chamber suite setting prose poems from Illuminations, Rimbauds final collection; Patti Smith addressed a classic rock anthem to him. How many artists greater and lesser have succumbed to the spell, how many artists manqus and ordinary readers have followed the Way of Rimbaud, it is impossible to say. I hope this book will speak to devotees, but I am writing for anyone who has the curiosity to embark on the journey, and particularly for readers who are attracted to the subject by an interest in the world that Rimbaud ventured into, which is as alien and exotic to us as it was to him. Java, too, was at a turning point in 1876, a medieval agrarian society permeated by magic, which was taking its first, tentative steps to join the modern world.

For readers who are unacquainted with Rimbaud or have only a vague recollection of reading a few baffling poems in a school anthology, I prefix an introduction, which sketches the outlines of Rimbauds life and work to the age of twenty-one, when he embarked for Java. Ive tried to propose ways of considering his work that may intrigue converts yet not chase off the curious. While Rimbauds voyage is an absorbing story in its own right, it seems essential to me that every reader bring to it a rudimentary knowledge of the voyager theyre coming to grips with.

![Nzenwa I. U - Java Basics: An intro to Java and the Java developement [development] environment](/uploads/posts/book/109245/thumbs/nzenwa-i-u-java-basics-an-intro-to-java-and-the.jpg)