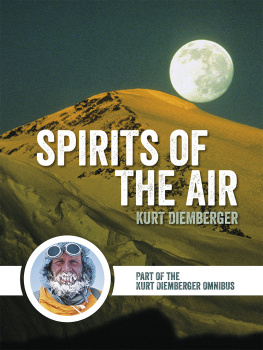

I could never have finished this book without thinking all the time of Julie and her wish, to pass on to others what we were living for. Besides herself it was Julies understanding husband Terry, her early climbing partner Dennis Kemp and perhaps in the most significant way her martial arts teacher David Passmore who opened up a world for her that was very special.

To write about these events on K2 was hard and it took me almost two years to complete the book. I want to thank my wife, Teresa, for her incredible patience. Many others helped too: Audrey Salkeld who translated the book into English; Choi Chang Deok who helped me clear up some of the mystery hidden in Korean hieroglyphs; Charlie Clarke and Franz Berghold, high altitude illness specialists; Xavier Eguskitza, John Boothe, Peter Gillman, Judith Kendra and Dee Molenaar even my daughters, Hildegard and Karen, have contributed to this work.

I must also thank those who made it possible for me to start writing at all: Gerhard Flora in Innsbruck and Hildegunde Piza in Vienna, who treated my frostbite, Enzo Raise in Bologna and the staff of Pembury Hospital in Sussex. Mrs Susi Kermauner in Salzburg took me to her rusty typewriter to start my first chapter and months later my little son Ceci taught me how to use the computer. There are many others who are not named.

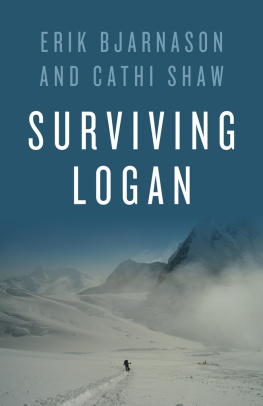

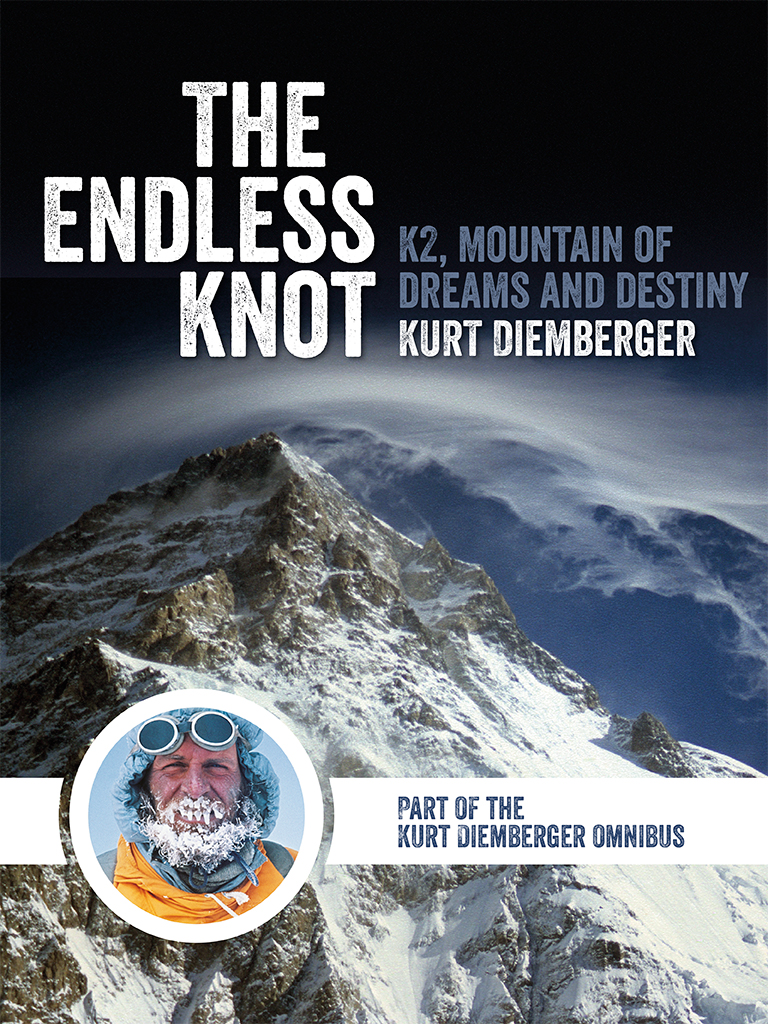

K2 from both sides

K2 from both sides, that was to have been the title of this book. Julie and I wanted to write it together. On my own, now, I find myself fighting shy of getting started.

Come on, Kurt!

Well then: testing, testing This typewriter seems all right, the ribbon is new and all the keys are functioning. The only thing thats needed is for the builders on the roof outside to stop their bloody noise. A neighbour on the other side was mowing his lawn all morning that, at least, has finally stopped unless he is simply taking a rest. Perhaps a nip of whisky will help me face all these distractions. I must type with my thumb because the fingers of my right hand are still too painful to use. Fingers, I say I mean whats left of them after the frostbite.

Perhaps I can at least set my new index finger to work thats not too bad. I wonder if Susie has a finger-stall? Using only the thumb makes it hard to concentrate on what I want to say. I should try dictating into a tape recorder, I suppose, and then type it up that way it would just be a mechanical action, and it wouldnt matter whether it was comfortable or not. But you do need peace and quiet to write on tape not for the writing, exactly, I mean for the recordddddddddddddddddddddddddddd

dddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddddding.

The d got stuck. Cest la vie! Difficulties are there to be overcome. I fiddle the typewriter key backwards and forwards, until at last it moves freely again (the arm of the letter key, I mean.) Now where were we? Ah, yes I mean for the recording. The one person you could have in the room would be the person to whom youre telling the story thats the only possibility. Otherwise, you have to be totally on your own, and with no interruptions, so that you can find the centre as Julie so often used to say and which she explained best, perhaps, in connection with meditation or with the martial arts like Aikido or Budo. There the centre has its importance not only for your mind, but also your body. Oh, those damned builders! The noise of sawing boards chases all thoughts out of your head. Today, I can see, is going to be a battle against innocent opponents. But perhaps it will also reinforce my resolve, since this book is something I really want to write for Julie, for me, for all those who understand. It seems senseless to have lived through all this only to have it disappear without trace.

Even then, it would not have been meaningless. It made sense for both of us at the time, representing the fulfilment of a lifetime It is about realisation I want to tell, a realisation that took place over only a few years, years during which K2 stood over us, remote and chill, yet more beautiful than any other mountain. A symbol, it seemed, of all that is unattainable.

An eternal temptation.

Will we ever come back to K2? Of course we will.

(Julie Tullis, 1984, in Urdokas on the Baltoro Glacier)

Introduction

A real book needs more than just a good writer. It needs a deep conviction, a promise to yourself, to others. I could never have finished this book without thinking all the time of Julie and her wish, to pass on to others what we were living for, to have them participate and writing down our experiences made it real. It was a way of continuing our team, a conviction that grew during my lonely descent on the Abruzzi after the fatal blizzard. It was a promise. Thus, the mountain and our thoughts will be within these pages.

Anything is possible, Julie used to say. She had a very strong will, was positive, determined and active. However, at times she would just sit still, listen to the sounds of nature, let her mind glide away into the space between the leaves of a tree, between the shimmering walls of ice towers, or up to the clouds beyond them. It was not only Julie herself who made our great days, those years and with them, this book possible. You almost never find that your achievements, your dreams, become real without the actions, influence or help of others. Besides herself, it was Julies understanding husband Terry, her early climbing partner, Dennis Kemp, and perhaps in the most significant way her martial arts teacher David, who opened up the world for her very special, uncommon personality. Julie has dedicated several chapters of her beautiful book Clouds From Both Sides to them.

When I wrote this book I considered also how much it might mean to her friends. Our time in the Himalayas were her last years, bringing her the greatest fulfilment as a creative person, not only with the summit of K2, our dream mountain. It was a way of ascent to yet another realisation. Then it all ended abruptly in the blizzard at 8,000 metres.

To write about the events up there was hard, sometimes a real struggle, but it had to be. Ill never be able to accept what happened, but at least it should never be repeated. It took me almost two years to complete the book, and I want to thank Teresa, my wife, for her incredible patience, as well as Audrey Salkeld, who translated the book, for hers. Many people helped: Choi Chang Deok, a priest, was sent to me, perhaps by providence, to clear up the mystery of this tragedy, hidden in illegible Korean hieroglyphs; Charlie Clarke and Franz Berghold, high altitude illness specialists; Xavier Eguskitza, the indefatigable chronicler, John Boothe, Peter Gillman, Judith Kendra, and Dee Molenaar even my daughters Hildegard and Karen have contributed to this work!

And I must not forget those who made it possible for me to start writing at all: Gerhard Flora in Innsbruck and Hildegunde Piza in Vienna, who treated my frostbite; the Pembury Hospital in Sussex which saved me from a sudden lung-embolism in the aftermath of K2; Enzo Raise in Bologna, who recognised at the last minute my totally unexpected malaria, probably caught on my way home in the aeroplane I almost died from it. While I slowly recovered, Mrs Susie Kermauner in Salzburg took me to her rusty typewriter in that two-hundred-year-old house and I started the first chapter. Several months later, in Bologna, my little son Ceci interfered with tradition: he taught me how to use the computer! Oh, finally, Dad he said.