P LATE 1: B LOSSOM (clockwise from top left): L UCAS B RONZE; S HINSUI; S UMMER B EURR D ARENBERG; C ATILLAC; S ANTA C LAUS

CONTENTS

www.thebookofpears.fruitforum.net

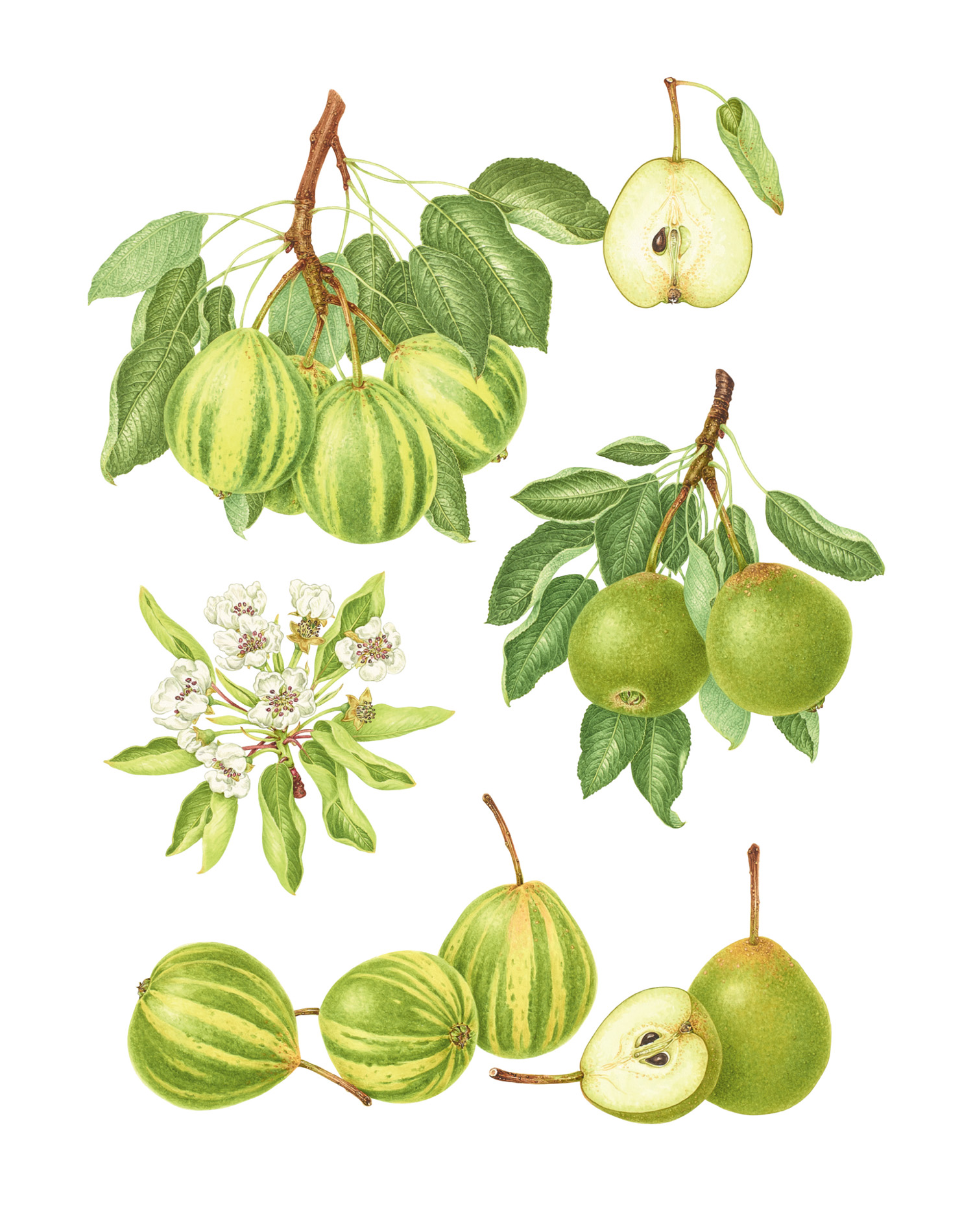

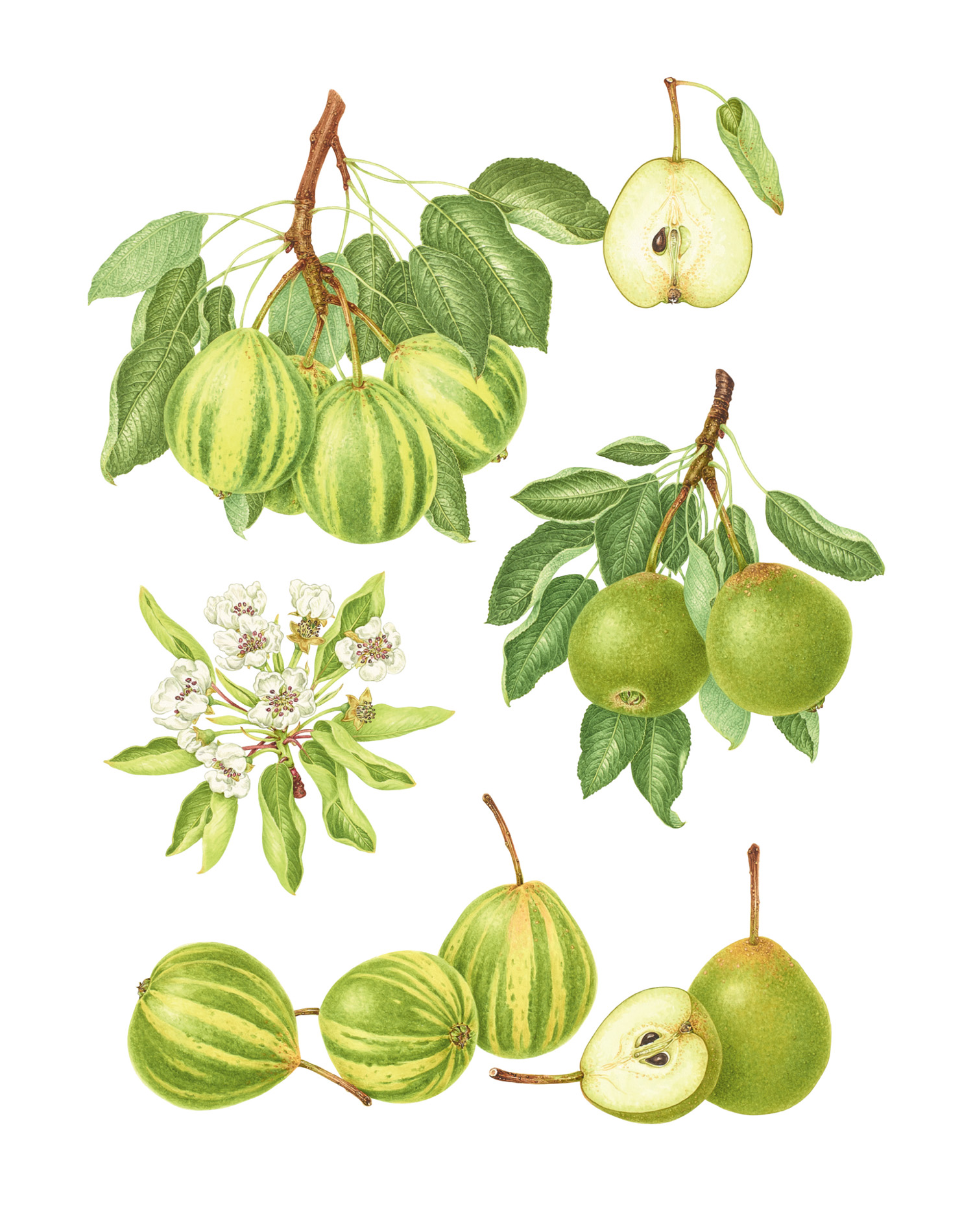

P LATE 2 : C ITRON DES C ARMES AND C ITRON DES C ARMES P ANACH

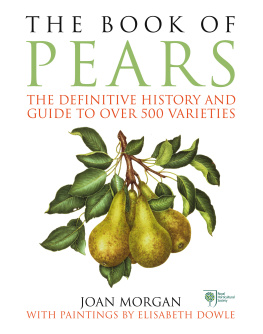

ABOUT THE BOOK

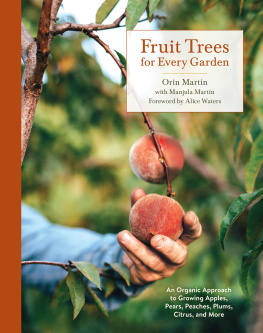

This extraordinary and unique book is an indispensable and one-of-a-kind guide. It tells the story of the pear from its delightful taste and wonderful appearance to breeding and cultivation, following the fruits journey through history and around the world.

Beautifully illustrated with 40 botanical watercolour paintings by Elisabeth Dowle, The Book of Pears is the most up-to-date and comprehensive guide to the pear. Moving through continents and cultures, Joan Morgan celebrates the pears long history as both a fresh and cooking fruit. Revealing the secrets of the pear as a status symbol, some of the most celebrated fruit growers in history, and how the pear came to be so important as an international commodity.

The pear directory, which makes up the second half of the book, covers the worlds ancient and modern varieties, each with full tasting notes and historical, geographical and horticultural detail.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joan Morgan PhD is a pomologist and fruit historian, internationally renowned for her work on apples. In recognition of her work, Joan has been awarded the Royal Horticultural Societys Veitch Memorial Medal (for contributions to the advancement of the science and practice of horticulture), and she is one of only 50 recipients of the Institute of Horticulture Award for Outstanding Services to Horticulture and is an Honorary Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Fruiterers.

Joan is closely associated with the UK National Fruit Collection, Brogdale, Kent; The Book of Pears gives a Directory to its Pear Collection. She is Chairman of the RHS Fruit Trials Forum and Vice Chairman of the RHS Fruit, Vegetable and Herb Committee.

Joan Morgan is the author, with Alison Richards, of The Book of Apples, The New Book of Apples, A Paradise out of a Common Field: the pleasures and plenty of the Victorian garden and a main contributor to The Downright Epicure, Essays on Edward Bunyard.

She has devoted many years researching and compiling The Book of Pears.

www.thebookofpears.fruitforum.net

Elisabeth Dowle is an internationally respected artist. She has been awarded seven Royal Horticultural Society Gold Medals, one of which was given for a selection of paintings included in this book. This is the 14th book Elisabeth has illustrated, including The Book of Apples.

Elisabeths paintings are exhibited and collected worldwide, held in many important institutions, and have been selected for the inclusion in the Florilegiums of Highgrove and the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney.

www.elisabethdowle.com

Chapter 1

THE PEAR

THE PEAR MUST be approached, as its feminine nature indicates, with discretion and reverence; it withholds its secrets from the merely hungry.

E DWARD B UNYARD, The Anatomy of Dessert, 1929

T HE P EAR

PEARS, AT THEIR most perfect, are sweet, juicy and perfumed. Their buttery flesh, which melts in your mouth like butter, glistens with juice; it can be sugary yet lemony, and scented with fragrances reminiscent of rosewater, musk, vanilla and other aromatics. Pears are potentially the most exciting of all the tree fruits. Cherries, glossy and succulent, and honeyed gage plums are wonderful in their time; apples will display a gloriously varied array of flavours from summer to the following spring; but the pear can be so much more exceptional in its luscious textures, boudoir perfumes and richness of taste. Gold to the apples silver, it used to be said.

The number of fine pears with the most prized buttery texture increased tenfold or maybe nearer twentyfold during the nineteenth century, pushing aside all the other older pears. Previously, pears for fresh eating were broadly of two sorts: those that softened on keeping to become juicy and melting in texture, with some possessing the sought-after buttery quality, and the less refined, firmer-fleshed pears. These latter pears were called cassante (breaking) in France, as they broke in the mouth, and they could be quite sweet and sometimes perfumed, like the best pears. The avalanche of numerous new, finely textured pears served not only to eclipse all the lesser sorts, but also to overshadow the pears role as a cooked fruit. This was the fate of the toughest, sharpest pears, which came to be called baking pears. Cooking or baking pears are not really edible as fresh fruit; they remain firm and tough-fleshed no matter how long they are kept, and some stay sound almost until the pear season comes around again. These pears are very sharp and astringent, yet with an attractive taste when cooked. Baking pears are barely known at all now in Britain, although still appreciated on the Continent where, in addition to being served as poached sweet fruit, they are eaten cooked with meats and turned into pickles and chutneys. There is a further group of pears the perry pear used for making perry, the pear equivalent of cider. This traditional drink is presently undergoing a great revival in its fortunes and valued especially in England and France, also in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Perry pears are small, coarse-fleshed and often fiercely astringent, but capable of being transformed into a drink that sparkles in the glass like champagne.

Some fine fruit and a glass of Madeira wine to complete the meal.

These different categories of pears were apparent by the seventeenth century, when the finest were eaten fresh along with some of the best cassante pears, perhaps with sugar sprinkled over. Baking pears went to the kitchen to be turned into sweet compotes, and perry pears made a drink to rival the best wine, its producers claimed. It was also in the seventeenth century that the European pear became much more widely distributed (the pear is not a native fruit of North America or the southern hemisphere). English and French settlers took the pear to East Coast America and Canada. Probably, the Spanish took pears to South America. Dutch traders introduced pears to South Africa, and British explorers took pears to Australia and New Zealand in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In these countries, as in Europe, the pear became a garden, orchard and market fruit, and also an export fruit shipped around the globe. With vast acres of new land opened up by the end of the nineteenth century and some of the finest varieties available, pear trees, like apples and many other fruits, were planted on a massive scale to found the present international fruit industry of which European production is also a part.