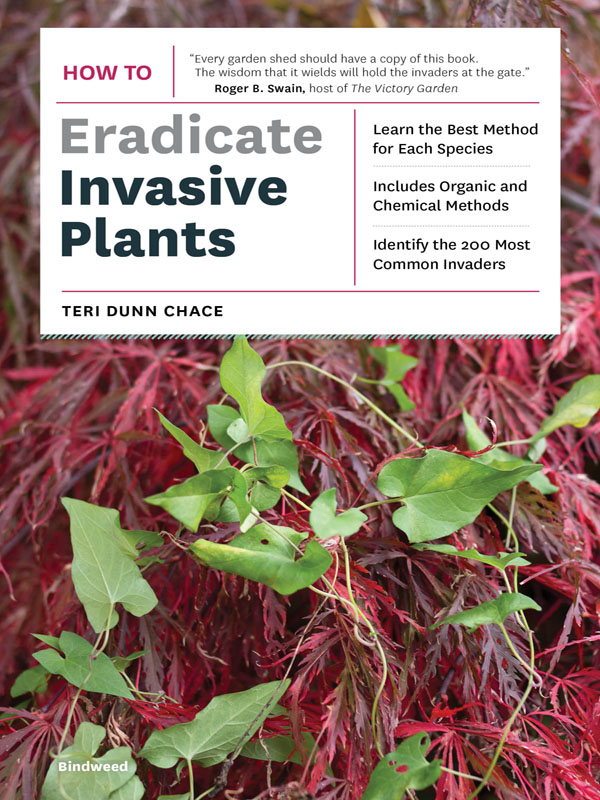

How to Eradicate Invasive Plants

How to Eradicate Invasive Plants

Teri Dunn Chace

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND LONDON

Mention of trademark, proprietary product, or vendor does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by the publisher or author and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products or vendors.

Copyright 2013 by Teri Dunn Chace. All rights reserved.

Published in 2013 by Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

timberpress.com

2 The Quadrant

135 Salusbury Road

London NW6 6RJ

timberpress.co.uk

Printed in China

Design by Laken Wright

Layout and composition by Ben Patterson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dunn Chace, Teri.

How to eradicate invasive plants / Teri Dunn Chace. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-306-5

1. Invasive plantsControl. 2. Noxious weedsControl.

3. Gardening. I.Title.

SB613.5.D86 2013

581.6'2dc23

2012030761

A catalog record for this book is also available from the British Library.

Dedicated to

Jon (Barney) Kleist

Contents

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.

JOHN MUIR

My First Summer in the Sierra, 1911

Introduction: Weedy Words

Earthlings, gardeners, fellow Americans: we have a problem. We have a weeds problem. They are everywhere. They have encroached on our roadsides, wetlands, salt marshes, lakesides and creeksides, and damp ditches. They have invaded our farmlands and orchards, fields and meadows. They want our golf courses and public parks, our back yards and front yards. They are already in our vacant lots, sidewalk cracks, property perimeters, and neglected and unwatched corners.

The lines we see or create between public land and private yard do not halt the spread of weeds. Some can clamber over a fence or wall or sneak into, or out of, a garden. Wind, water, birds, and more easily transport the seeds of some plants and the viable bits (that is, seedlings or root fragments) of others.

The common dandelion is a classic example. It pops up uninvited in front and back lawns, in city parks, in curb strips, in playing fields. Maybe when you were a kid, someone paid you a nickel per plush yellow flower to yank them out before they turned into white puffballs. Otherwise poof! A slight breeze or the kick of a shoe, and those tiny seeds parachute all over town, setting the stage for an even bigger invasion next spring and summer.

Today, all manner of unsavory plants are increasingly in the news and on our radar, so to speak. Perhaps youve noticed that a crew of volunteers has been dispatched to a local wetland to undertake the hard work of digging up purple loosestrife rootstocks, which, once theyve been in place for a while, are bulky as a buried tire and insidious as a tumor. Or, maybe you have observed in passing that the stands of Japanese knotweed on the outskirts of town are multiplying every year, sucking up water and nutrients and shoving aside all other plants. Kudzu has already engulfed and devoured much of the South. Cheatgrass, especially when it dries out in the hot summer sun, is blamed for giving devastating wildfires in the West entirely too much fuel. Freshwater boaters are warned with strategically placed, detailed signs to rinse off their hulls before and after putting into a lake or stream, lest they spread invasive, alien plants (and creatures). And so on and on.

Worldwide Weeds

Culturally, we live in a global village, thanks primarily to a dazzling array of technological advances in transportation and communication. Mixing it up, traveling and trading, importing and exporting, exploring and exchanging ideas and materialsall this is generally considered not only inevitable but also desirable. Awareness and diversity are good, indeed exciting and enhancing. We inhabit a web that binds us all together and seemingly shrinks the world.

Meanwhile, smaller, minority voices can also be heard, protesting that sometimes the local, the unique, the indigenous, is being threatened or lost. An American friend who traveled in Tanzania related that, in a remote bush village, she encountered a small boy wearing a tattered but recognizable John Lennon t-shirt: Heaven knows where he got it or what its travels were, she reflected in her blog. It was so jarring and incongruous. Was I glad or sad to see that shirt?

A similar sensation may assail the informed gardener or botanist who spots a foreign plant in familiar ground. And what about the plant collector who imports and plants, say, a nifty exotic flowering akebia vine from Sichuan Province, China? Or the avid, adventurous gardener who snaps up a seedling of foreign origin at a specialized nursery or flower show, just because it looks to be beautiful, just for the challenge, or even simply because he or she values rare or cutting-edge plants? Even if the import is untested in this country?

Yes, gardenersfor a variety of aesthetic and practical reasonshave occasionally been credited or blamed with introducing a problem plant to American soil. The examples are legion. Will the aforementioned akebia, so lovely and tame in situ, turn out to be a monster here? Will importers and boosters of the rare, foreign, and exotic be praised or blamed in a few years or decades?

A thicket of Japanese knotweed hovers on the sidelines, annually encroaching into a well manicured lawn.

Not all introductions have been or are deliberate. In Weeds: In Defense of Natures Most Unloved Plants, British nature writer Richard Mabey cites a variety of other vehicles on which plants have hitched a ride: in ballast, in packing materials, in contaminated seed and feed, in fill soil, as well as in once-popular food crops and useful herbs that have gone rogue. Even on the smallest scale, most gardeners have, at one time or other, brought home a potted plant from the local nursery only to discover a stowaway tucked under the leaves, an unwelcome burdock or thistle.

Other plants have arrived with the best intentions, promoted as ideal for erosion control or low-maintenance landscaping. In Florida, the once-promising imported ornamental tree known as bishopwood has been rapidly wearing out its welcome by overtaking fragile native swampland communities. The agents? Native as well as introduced birds, which relish the seeds.

Occasionally an unsavory foreign relative of a native plant worms its way into and ultimately alters the gene pool, as is apparently the case with alders, to name but one example. All this brings to mind that pivotal moment in the sci-fi classic The Andromeda Strain when a scientist exclaims in panic, Therell be a thousand mutations! It will spread everywhere! Well never be rid of it!

Agents of Movement and Dispersal of Invasives

packing material (hitchhikes in on)

contaminated hay or straw (hitchhikes in on)

ballast (stows away in)

seeds eaten by birds or animals (which then deposit them in a new location)

seeds attached to animal fur, human clothing or footwear (which then detach or fall off in a new location)

seeds or viable fragments embedded in topsoil, mulch, or fill

seeds or fruit that float on water (such as sea, river, stream, or lake) to a new location

Next page