The stories were always for me to do, I said.

What do you mean by that?

Richard gave me a certain kind of look, a look that came from being up too late and drinking tequila with me at a glamorous bar, but also the kind of look that showed that he knew me very well.

What do you mean by that? he said again.

Wed been talking about my short stories, the collection Id put together and the kinds of short stories I was interested in, though Richard said that they were the kind that would never sell. Nobody buys short stories anyway, hed said earlier. No one thinks theres enough going on.

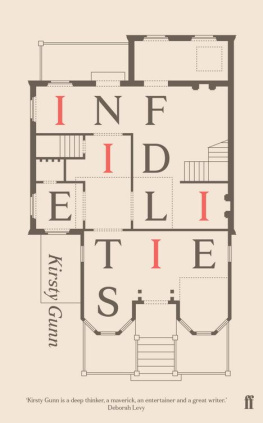

I just mean, I said, that it was always me behind the whole thing. The collection, the idea of those stories Id written. It was always me, inside them, I was involved. Like the one I was just telling you about, with the woman and her husband, the one thats called Infidelity That one. But all of the stories. All of them. I was never going to pretend that theyd just, you know, arrived invisibly on the page. I was always there.

Phew, said Richard. He drained his little tequila glass, and set it down. Youre there, all right, he said.

And Im also right here.

Youre the writer, thats for sure, Richard smiled, that long, slow smile I knew so well. Youre the one, standing by, just like old James Joyce said. He tapped his little glass. Loitering in some doorway, chewing on his fingernails or whatever

Not chewing, I said. I took a sip of my own tequila. A hundred per cent agave just like my friend Jennifer from Mexico said is the only kind you should ever have.

Paring, I said to Richard, taking another sip. Paring his fingernails. Thats how Joyce described it, his definition of the artist standing by but, sure, youre right, hes there, shes there

Richard shook his head, he said Phew again. I leaned over and gave him a quick kiss, not on the forehead or cheek, but on his mouth. He closed his eyes then. I closed mine. When I opened them he was looking at me.

Richard. Richard, Richard, Richard. Still himself, still the same man, after all this time, with that same wrecked and gorgeous look Id been so taken with all those years ago. The same Richard. Drinking too much. Doing everything too much but as though nothing would ever touch him. As though nothing would come close. He still wore the same kinds of clothes he used to wear when we were together, had the same smell of smoke and leather and some old fashioned cologne, like some fabulous old club from the eighties. Richard. Richard, Richard. Richard.

Thats the artist standing by, but coldly, I said, I realised I was talking in a very low voice. I was practically whispering. Joyce uses that adverb specifically, I said. So I am not the same. Im not like him. Im not coming in on something and using it. Im not discovering the story, and then writing it down. No. From the beginning, I was there. Im not cold at all, you see. Im in the midst.

By now Richard had my hand in his hand. Very gently, he was stroking one of my fingers with his thumb.

I should go home, I said. Its late. All this talk of short stories, my collection I should never have told you about any of it. Bringing you into it like this.

Its just made you want to go home, Richard tapped my finger with his thumb. But you dont need to go home, not yet. Call your husband, call your children.

Its already too late to call them.

Well, Richard said. Nevertheless. I want you to sit here, right here where you are. Look at us, in this lovely place He gestured with a nod of his head, at the restaurant around us, all the yellow lamps and the marble, all the silver buckets and the champagne and the oysters and the ice. I want us to stay right here, he said. For now. Please. Dont go just yet.

Oh, You I said.

No one reads short stories anyhow, he said, for the second time that night. So you dont need to worry about that. Were safe. You and I. And all those things youve written Theyre only here he touched the side of my head and here, and he touched my heart. Theyre nowhere else.

Theyre in the book, I said. Infidelities. Remember? The whole collections finished, its done. And I leaned over and I kissed him properly then, I kissed him on his lovely mouth.

Im glad weve gone out, he said, after Id finished. Lets stay out. Who knows. Maybe well never go home, you and I. Maybe well just say were never coming home again.

Contents

Bobby had got back late from the pub and said theyd all been talking about it. About this guy, the real thing, he said, from Tibet or someplace like that by the look of him, in the saffron coloured robes and with his little bowl and not speaking a word, just arriving in the midst of the village that day and taking up some kind of position, actually, was the way hed described it, right there in the covered market under the clock.

And this was What? Twenty years ago? More. Yet even now when all that time has passed and Helen can think about these things, look back upon episodes in her life and reflect upon them imagine her way into them, sometimes, is how it feels she considers how something did seem to begin for her then, that day, that night, in a way continues to begin. It was there in that phrase of Bobbys: Taking up some kind of position. As though even he, in those words he used, had been aware somehow that the image of a monk from another world could come to sit squarely in the midst of their marriage, sit between the two of them, make it clear how far they were apart.

Helen had just carried on filling the dishwasher while he spoke. Bobby always described anything that happened as though it was his own personal experience what was happening in the world, in Iraq, say, or in Ireland as though hed just come from those places himself when everybody knew he just went to work at the agency and wrote the ads there like hed always done, stopping each night at The Black Lion for a quickie after he got off the bus, before he came home. He was good at it, holding forth like that. She had put the last of the childrens things, their little plates and bottles, into the dishwasher and closed the door, and just let him go on, claiming ownership of something that he hadnt been part of, expecting her not to know the difference. Now he was talking about Tibetan practice and what it was to be a monk in this day and age, what it might mean to have one arriving here in their little Oxfordshire village, settling himself down in the covered market, right in that same place, he said, where Helen had had her organic stand last summer when shed been in the mood, remember, to do that sort of thing.

Helen sat down herself then. With Bobby at the kitchen table, the dishwasher running and the casserole up behind her on the hob She said, Listen, I know.

Shed always had to do that, to get his attention, would have to sit down and actually face him, speak into his face, have him see her with her mouth moving

So shed said, Listen, I know, sitting right there in front of him, and she remembers now the look on his face after shed spoken, just for a second, maybe, but terrified, terrified.

Then he got up to get another beer from the fridge.

It came from his job, of course. That thing of being used to hearing your own voice, knowing you could convince people with the way you spoke as much as what you said. Ever since Helen had known Bobby hed described himself that way, like he was proud of it, that Helen would have to turn from what she was doing, take the seat right there before him to intervene in the run of his own conversation.