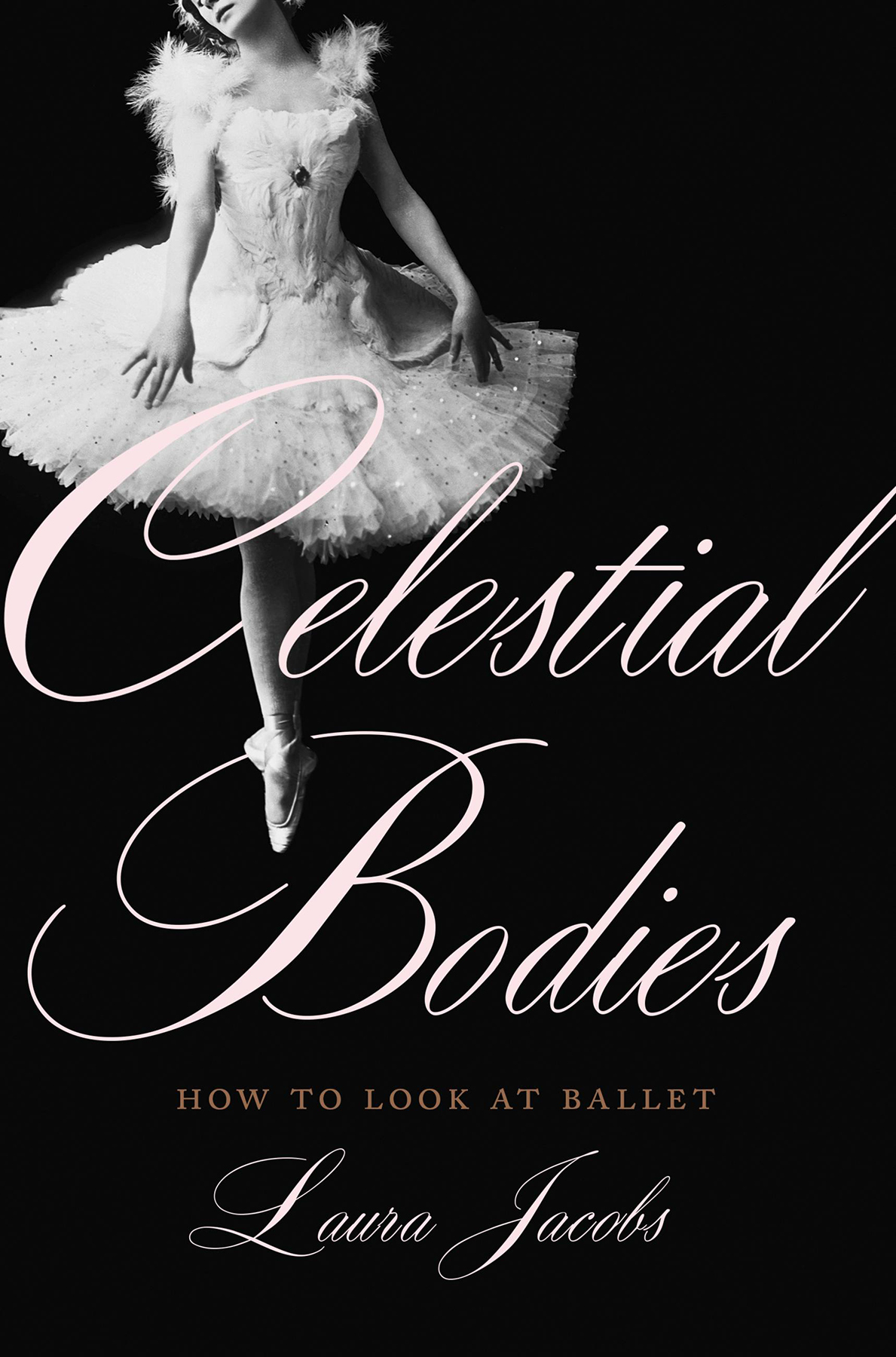

H OW TO LOOK AT BALLET? W HILE WRITING THIS book, there were moments when I felt it could have been subtitled How to Think About Ballet. We assume that how to look and how to think are two different things. Yet when it comes to balletto all dance, actuallylooking and thinking, separate faculties at first, eventually begin to work as one faculty. Looking becomes a form of thinking.

We know that dancers develop their bodies to a point of exquisite coordination. But we in the audience do the same with our seeing, so much so that the dance is actually happening on both sides of the footlights. We begin to place our trust in visual echoes, references, and metaphorsglimpses and images that we assume everyone sees but that, as we learn later when talking to others, sometimes only we have seen. Thats the way this art is. And while there is often consensus on what a gesture, a step, an entire ballet may mean, interpretations can also vary widely. We all bring our own history to the ballet, each of us with his or her own interpretative framework, and these too inform a performance.

Through aural memory, which is stored in the brains auditory cortex, humans have the capacity to retain whole songs, symphonies, and scores seemingly forever. Sight is different. We remember what weve seen in snapshots or, at best, in seconds of live capture. Most of us cant replay in our minds eye long skeins of movement from past performances. And anyway, on a big stage there is no way to take in every inch of whats happening. This means that no matter how many times we see a ballet there will always be something new to wonder at, to puzzle over, to see for the first time. With a change in cast, there will be dancers who emphasize different aspects of a role and bring different meanings to a work. Because we cant ever completely possess a ballet, it continues to surprise.

This freedom from finality is why companies can keep the greatest ballets perpetually in repertory, where they circle around and back, year after year, bringing new insights and deepening discovery. Paradoxically, this rhythm of cyclical or eventual return, of ballets never gone for long, also brings a reassuring stability, a steady heartbeat, to the art form. Ballets can be delicious meringues, old friends, vintage wines, great loves, grand banquets, spiritual sustenance, long-standing enigmas. Some ballets (we each have our own list of these) are like difficult relatives at a family gathering: here they come again, oh well, cant hurt to catch up and see how they are doing. Other ballets loom large. What would December be without The Nutcracker? It is as loved and leaned upon as Handels Messiah and Dickenss A Christmas Carol.

As we become more comfortable with our own cognitive leaps and turns, our own wanderings within a work, we will bring new spins to a ballet we thought we knew. The greatest ballets reward endless looking. They are glass-bottom boats, Prousts madeleine, C. S. Lewiss wardrobe, Bluebeards castle, Freuds couch, Dr. Caligaris cabinet, Kubrickian space odysseys, and superkinetic PlayStations. They take you places you never dreamed of going.

Ballet is energy and energy is life. As with any foreign territory, we can approach an evening at the ballet with a fear of the unknown or with an open heart, a belief that success is in the seeing. The way to go is with an open heart.

T HIS BOOK IS NOT A HISTORY OF BALLET AND DOESNT need to be. There are many fine histories already published, and there will undoubtedly be many more. Still, I have organized my chapters so that themes emerge in a chronological way that roughly coincides with the arts development through the last three-plus centuries. Along the way I have quoted from some of the fundamental books on classical dance, as well as more recent books on the subject. If I have quoted from a book, a critic, or an artist of the ballet, it is an implicit recommendation of a voice I respect. Certain names will turn up again and again. All quotes from the vivacious Thophile Gautier come from The Romantic Ballet as Seen by Thophile Gautier, 18371848, a collection of his reviews and articles translated by Cyril W. Beaumont. All quotes from Akim Volynsky come from Ballets Magic Kingdom, the first English translation of Volynskys work, including his shining treatise of 1925, The Book of Exaltations: The ABCs of Classical Dance. And all quotes from Agnes de Mille come from her terrific memoir of 1951, Dance to the Piper. The learned writing of both Cyril Beaumont and Lincoln Kirstein is pulled from many of their books. Gail Grants Technical Manual and Dictionary of Classical Ballet is a classic, and Ive quoted from this book liberally.

When it comes to the classical vocabulary, I have defined steps and terms wherever I think it is necessary, and as succinctly as possible. When I have chosen to mention a step without a definition, its because I think context will make things clear. I also trust that readers can jump onto the internet and pull up either a dictionary definition or a YouTube demonstration. Many of the ballets discussed in this book can be viewed for free on YouTube, but Ive mostly refrained from making recommendations because whats online today may, due to copyright laws, be gone tomorrow. Finally, when using the word