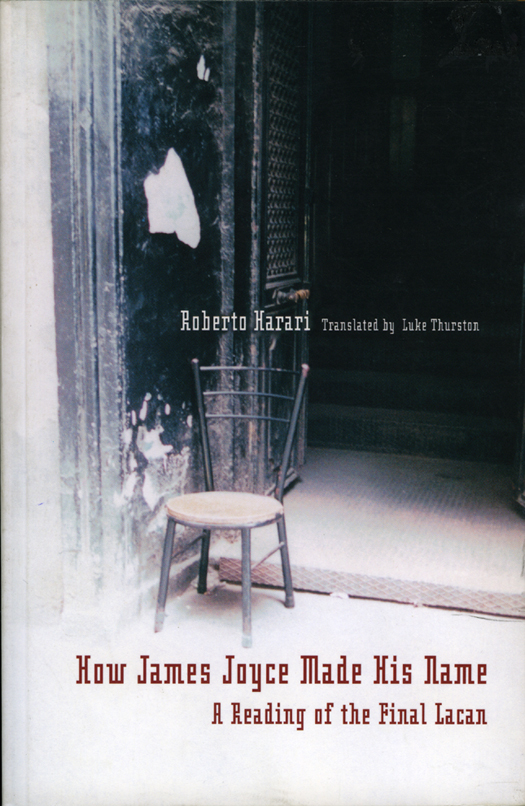

Originally published in Spanish as Cmo se llama James Joyce?

Copyright 1995 Roberto Harari. Translation copyright 2002 Luke Thurston.

Production Editor: Robert D. Hack

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from Other Press LLC except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Harari, Roberto.

How James Joyce made his name : a reading of the final Lacan / by Roberto Harari; translated by Luke Thurston.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-659-1

1. Joyce, James, 18821941Criticism and interpretationHistory20th century. 2. Lacan, Jacques, 1901Contributions in criticism. I. Title. II. Series.

PR6019.O9 Z574 2002

823.912dc21

2001036649

v3.1

For my wife Diana,

who with her love, her patience,

and her clear-headed encouragement

accompanies all of my psychoanalytic endeavors.

(bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!)

J. Joyce, Finnegans Wake

I wish for blankness, emptiness, the absence of words. But it is always words that speak inside my head, speak without ceasing.

M. Didier, Contrevisite

Contents

Prologue

Great bows on her slim bronze shoes: spurs of a pampered fowl.

J. Joyce, Giacomo Joyce

Yo to dor

To dor oo hormoso

To dor ono coso

Ono coso co yo solo so

COFO

Cabrera Infante, Tres tristes tigres

Exile is a kind of living apart, a feeling of being limitless like a man without body or emotion, anonymous and without biography.

H. Tizon, Experiencia y lenguaje

I

In the present work I pursue the pathway opened by my introductory studies of Lacans Seminars 11 and 10 (Buenos Aires: Nueva Vision, 1987; Buenos Aires: Amorrortu editores, 1993). The subject of the work is Seminar 23, Le sinthome, which was delivered by the French psychoanalyst in 19751976. In my opinion, the intent, significance, relevance, and context of this choice are sufficiently explained and developed by the work itself for me to dispense with discussing them here. The fundamental ingredient of my books is the text transcribed from recordings of my classes, given at the Centro de Extension Psicoanalitica in the General San Martin Cultural Center at Buenos Aires. I followed the same procedure here, even if I was amiably requested to do so by the Secteur dEtudes et Recherche en Sciences, Cultur, et Socit of the Center, directed by Adriana Zaffaroni. I am therefore profoundly grateful to her, and also to the audience at San Martin, which once again in 1993 packed the lecture hall to accompany, with interest and with a striking degree of receptivity and discussion, a topic that was completely new for very many of those present, regarding both its psychoanalytic-topological and its literary aspects. On this occasion, I have respected the breaks set by each of the ten classes, in order not to efface the productive traces of the books origin. Despite this, as can be seen from the publication dates of a section of my bibliography, my growing interest in those chapters dealing with the seminar caused me to extend the initial text by including themes and approaches that did not form part of my classes at San Martin, nor indeed were addressed in the seminar itself. In this sense, I have observed in myself a certain retreat, with full admiration and respect, from Lacans text, in particular when I have turned to his own sources. As will be seen, I do not always share the same conclusions as Lacan; this Introduction, therefore, seeks to enable the development of a judgment governed by reason, not by acritical fascination. On the other hand, I have not refrained from using schemas, comparative tables, and drawings whenin my own view, naturallythe argument requires them. It is in this sense that I would stress the guiding thread of my work: to attain the maximum clarity of exposition without making any illegitimate concessions. Rigor does not equate with obscurity, just as one should not confuse didactic verve with the proverbial jargon of psychoanalysis.

II

I would also like to express my gratitude to Lorena Reiss, for her meticulous and devoted labors with the word processor. The many corrections of the original text have also benefited from her comments on the writing itself.

III

As the epilogue of this Prologue, we might introduce immediately one of the books principal subjects, if only as an indication. If there is indeedor perhaps there only should bea post-Joycean psychoanalysis and literature, and given that my text deals more with the first of these, I would like to include here a few references to post-Joycean writing as seen in Spanish. This is bound up with the difficulty of reading Joyces Finnegans Wake, which obviously requires, first, a great mastery of the English language. Since it is radically untranslatablea point that my book duly acknowledgesit is good to know that in Spanish there are works of great significance able to arouse the jouissance of a post-Joycean act of writing. Post here, of course, does not define a chronological time but a subjective position before the letter. This is why Gongora, and to a lesser extent Quevedo, form part of this lineage. As does Julio Cortazars Rayuela, G. Cabrera Infantes Tres tristes tigres (see above epigraph), L. Marechals Adan Buenosayres, and J. Rioss Larva. Let us leave the final word here to this last author (a contemporary, at last), in a kind of wreath or emblem that serves as an ideal hinge for the reader to begin immersing him- or herself in what my pages set forth: Hourra, Mr. Joyce! The animator again straddles the microphone. He rejoyces in the name of Freud. May the joy continue!

Joyce and Lacan: A Quadruple Borromean Heresy

S eminar 23, Le sinthome (19751976), is probably the last moment in the whole of Lacans teaching where a rigorous internal unity is emphasized. What emerges there is a coherent reconceptualization of many themes that relate not only to the clinical practice of psychoanalysisalthough they have a considerable bearing on it, and we will see howbut also form part of a sort of tradition: the psychoanalytic turn to art, in particular to literature, the aesthetic domain that is closest to the analytic experience. Psychoanalysis is connected to literature through its work with spoken language; as analysts, we are inevitably located on the borders of the literary field. In this sense, in the seminar we are to explore, Lacan uses his engagement with Joyce to set in motion transformations that are without precedent in any writerand that, in the first place, put in question certain prior phases of his own teaching.

At various points in our study we will invoke puns and wordplay, in a way necessarily entailed by Lacans thought. Some people might find that, as such, these