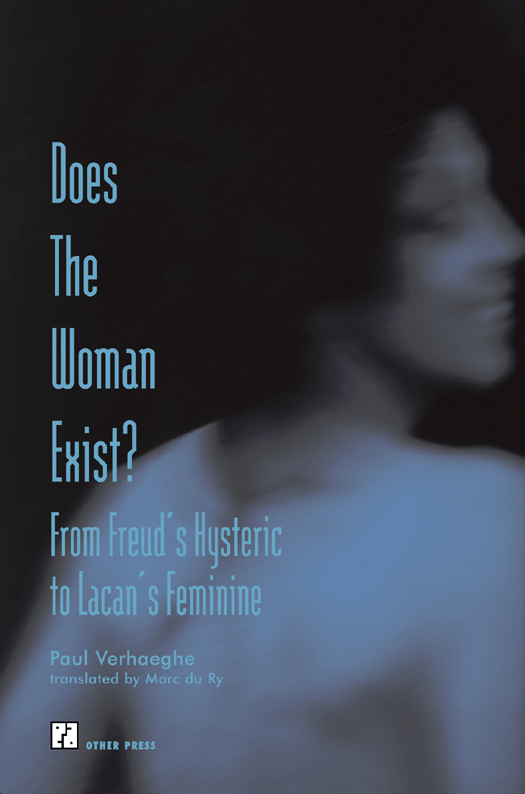

First published in English 1997; revised edition 1999.

Production Editor: Robert D. Hack

Copyright 1999 by Paul Verhaeghe; 1996 Acco (Academische Coperatief c.v.). English translation 1997 by Marc du Ry. Originally published in Dutch as Tussen Hysterie en Vrouw.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from Other Press LLC except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Verhaeghe, Paul.

(Tussen hysterie en vrouw. English)

Does the woman exist? : from Freuds hysteric to Lacans feminine/Paul Verhaeghe; translated by Marc du Ry.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-671-3

1. Psychoanalysis. I. Title.

[BF173.V4513 1999]

150.195dc21 98-55449

v3.1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Judith Feher Gurewich

Freud discovered psychoanalysis by following the path of hysterical desire; along the way he encountered the unconscious, the power of transference, the formative function of the oedipal complex, the theory of infantile sexuality, the lure of fantasy, and the death drive. However, Freud made one mistake: he wanted to stay ahead of the hysterical game. He thought he could give his hysterical patients the answer to their question, What does a woman want? He believed they wanted a master who held the secret of their most unknown wishes. Yet Freud could not crack the riddle of sexual difference. The female side of human desire refused to be caught either in the passive position or in the procreative role. His clever Dora had little patience with such dire prospects. Piqued by her dismissal, and frustrated by the interminable nature of the analytic process, Freud searched until the end of his life for the signifier that would finally seize the mystery of femininity.

Lacan took up the challenge and offered an unexpected answer to the riddle: Freuds dark continent is a hysterical fantasy that keeps the analyst in a false position of mastery and prevents the treatment from being brought to a close. By breaking down the collusion between the hysteric and her master, psychoanalysis allows the subject to sever the tie with the one who is by definition impotent to provide an answer to an impossible question.

Paul Verhaeghes lucid presentation of the dialectical process that carries Lacan through the evolution of Freuds thought offers profound insights into the place of hysterical discourse in the social fabric. Patiently and carefully Verhaeghe applies the Lacanian grid to the Freudian text and achieves the extraordinary feat of explaining Lacans formulations without turning the project into a mere recapitulation of the theory. Verhaeghe, along with Serge Andr,of Lacans own take on Freudian ideas, but also of the arrays of interpretation that emanate from other trends of post-Freudian literature, including feminist revisionism.

The approach chosen by Verhaeghe reveals a side of Lacans theory that is often forgotten: Lacan exists only when read in a dialectical relation with the Freudian text. Lacans conceptual framework makes sense only when applied to different moments of Freuds thinking. Lacans famous registers of the Real, Imaginary, and Symbolic cannot be viewed as the new foundations of human subjectivity (a common tendency in postmodern theories). They are rather the missing pieces of the Freudian corpus, the very ones that resolve its apparent paradoxes and contradictions. As Verhaeghe points out, the three registers were Lacans conceptual knife enabling him to dissect clinical practice in such a way that it honoured Freuds theory. Verhaeghes message is clear: It is Freuds passionate encounter with hysteria that enabled Lacan to give the unconscious a formal place in the social fabric.

In that sense, Lacans theory of the four discourses, remarkably explicitated by Verhaeghe, finally breaks down the historical divide between psychoanalysis and the social sciences. By recapitulating, in a formal system, our inability to match conscious intent with unconscious strivings, Lacan not only describes the dialectical reversal operative in the transference but also exposes the underlying dynamics of social interaction. While the discourse of the hysteric addresses a master who can resolve the mystery of femininity, the discourse of the master aspires to the knowledge that the hysteric believes he possesses. The discourse of the university, on the other hand, seeks a truth that is not in its library. Finally, the discourse of the analyst reveals that in the place of power and knowledge stands a divided subject who no longer confuses the object of desire with its cause. The discourse of the analyst in that sense succeeds where the other discourses have failed. It reveals that what appears unacceptable is at the end preferable. To lack the answer becomes the solution. Beyond the mysterious power of the master and the opacity of knowledge there is nothing to be found except the freedom of desire.

According to Verhaeghe, it is by following the shifts operative in the four discourses that we discover the fundamental lure that underlies the Freudian projectthe mystery of femininity is a hysterical set up. It is indeed the discourse of the analyst that demonstrates that desire has been sustained by a cause that was only an illusion. Indeed, isnt the feminine enigma the ultimate representation of what resists the grasp of both power and knowledge, the very thing that poetry can only allude to and that science ferociously attempts to control?

Such demystification of the dark continent does nothing less than to offer us a radically new utopian vision of social exchange: a world where human desire is set free from the beaten path of neurotic certainty; a world where people can distinguish among truth, knowledge, and power; a world that can accept that discourse necessarily will fail to represent what fundamentally does not existthat is the Woman.

Serge Andr, What Does a Woman Want, in press in The Lacanian Clinical Field, Other Press.

INTRODUCTION

The discourse of the hysterical subject taught him (Freud) this other thing, which really comes down to this: that the signifier exists. In gathering up the effect of this signifier in the discourse of the hysterical subject, he succeeded in giving it that necessary quarter turn which changed it into analytic discourse.

[Jacques Lacan, XX, 41]

One hundred years ago, Freud began a dialogue with hysterical patients. What was initially meant as a bread-and-butter job, a step away from the beloved laboratory and so a step away from the possibility of discovery, became a theory that would turn knowledge about man on its headand therewith all knowledge as such. The effect of this, which Freud considered the third narcissistic blow to mankind, is far from fully known.

One effect would seem to be the disappearance of hysteria, a disappearance coinciding with the worldwide acceptance of psychoanalysis. Conversion symptoms have become rarer and rarer, the great hysterical attack la Salptrire is today a curiosity to be nurtured. According to several historians, this disappearance is the result of the prophylactic influence of psychoanalysis. The worldwide dissemination of the insights produced by its theory has changed society to such an extent that hysteria has become superfluous and thus obsolete.