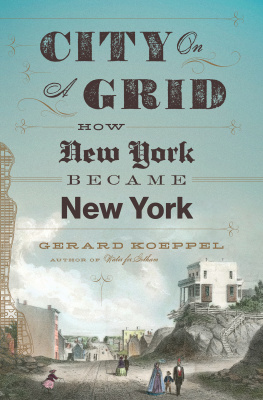

City on a Grid

Copyright 2015 by Gerard Koeppel

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, Third Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Set in 11-point Goudy by The Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Koeppel, Gerard T., 1957

City on a grid : how New York became New York / Gerard Koeppel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-306-82285-8 (e-book) 1. City planningNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 2. StreetsNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 3. Grids (Crisscross patterns)New York (State)New YorkHistory. 4. City and town lifeNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 5. Social changeNew York (State)New YorkHistory. 6. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)History. 7. New York (N.Y.)History. I. Title.

HT168.N5K64 2015

307.1216097471dc23

2015020980

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Diane, Jackson, Harry, Kate, and Scrappy

T his book got its start after the attacks that brought down the World Trade Center towers in 2001. The original trade center was built in the 1960s over a wide area of its neighborhood, in particular the intersection of Greenwich and Dey Streets, where, at the northwest corner one January midday in 1810, a mother helped her child pump water from a public street well. The scene was painted in watercolor by a French migre, Anne-Marguerite Hyde de Neuville, a prolific artist of early America who then lived across the street. This casualand my favoriteglimpse of Old New York showed modest wood and redbrick homes, dirt streets, bare trees, and a scattering of other New Yorkersa lumberman, a housekeeper sweeping her sidewalk, two men talking, a few ladies walking, and other neighbors going about their business on what appeared to be a mild winter day. (Have a look online; the image, Corner of Greenwich Street , is easy to find.) Over a century and a half later, the intersection of Greenwich and Dey disappeared beneath the plaza of the first World Trade Center.

Then, in the rebuilding after 2001, a smaller trade center emerged and, with it, the long-lost segments of Greenwich and Dey streets, ironically just for foot traffic, much as they were used centuries earlier. This got me thinking that the street arrangement of now densely urban Manhattan is more plastic than I imagined. Streets and corners can come and go, and come back again.

Next, I thought what if it was not the World Trade Center but, say, the Empire State Buildingnot at an edge of the island but at the citys physical heartthat came down: a trauma to daily life in the very center of the city. (This was a depressing thought but no longer unimaginableNew York has joined the family of existentially traumatized world cities.) How would that rebuilding go? Should the rectilinear street grid conceived in the early 1800s to accommodate animal transportation be rebuilt as it was? Or should new or modified forms be introducedradials, curvilinears, green spaces, water featuresbetter suited to a mass-transporting, post-industrial, resource-conscious city?

How, I thought, could I be involved in a conversation about possible changechange prompted by malevolent intention, devastating accident, or enlightened choiceto the urban fabric of New York City? Im not an architect, an engineer, an urban planner, a politician, or even an environmentalist who might claim direct input. Im just an historian. (Historians are like people who yell fire in empty theaters: no one gets hurt, often no one hears, and sometimes the building burns down.) I could, as an historian of the city, examine its oldest and most essential piece of infrastructureits famous rectilinear street gridwhich shapes everything else about the city, and offer the findings to anyone interested.

What I found is that the great grid had a very humble, almost embarrassing, even unworthy, birth yet, like a common object fetishized over time, it resists attempts to change it. This history of two centuries and counting, I reckoned, may be of use when and if the time for change comes. It is easier to move forward after the grasping fingers of the past have been pried open, often revealing that the extraordinary is ordinary and not so difficult to change. In the meantime, what follows can also be taken as just another story in the epic of how New York became New York.

There will come a time... when nothing will be of more interest than authentic reminiscences of the past.

Walt Whitman, Brooklyn Daily Standard , June 1861

But in analysing history do not be too profound, for often the causes are quite superficial.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, journal entry, November 1836

I f a picture is worth eighty thousand words or so, one image captures what this book is about. And if every picture tells a story, this image tells two. The photograph was taken during the winter of 188283 from the roof of a millionaire brewers new brownstone mansion at the crest of Prospect Hill, on the east side of Fourth Avenue between 93rd and 94th Streets. This was an evolving neighborhood of New York City, which then consisted of Manhattan only (the boroughs came a little bit later). The avenue and streets on this segment of the island had been laid in the 1850s, but development had been stalled by the loud and dirty locomotives of the New York and Harlem Railroad, running since the 1830s on surface tracks through what was then and for decades after countryside. Only after the tracks were sunk belowground and covered during the mid-1870s did scattered squatter shacks, small factories, and aging farms give way to merchant piles and developer dreams. The broad and freshly landscaped boulevard over the tracks would soon be renamed Park Avenue. And the hills high prospects would soon transition from referencing the natural view to reflecting broader social expectation: Carnegie Hill, appropriating the name of the neighborhoods richest new millionaire.

The image that tells this books stories, an albumen print by Bavarian-born Peter Baab, looks south from beer baron George Ehrets gabled roof at a city rising from the distance. On the right is the new avenue, airy and clean, visible for several blocks as it recedes into the sooty background; a scattered few of what will be solid walls of imposing apartment buildings front the avenue. Running across the middle ground is 92nd Street, intersecting the avenue as streets generally meet avenues on Manhattan: at a right angle. On the south side of the street, facing the camera, is a varied cast of structures representing the local past and future. From the corner stretches a new three-story brick row house with a half dozen entrance stoops greeting fresh sidewalk: a herald of comfortable multifamily living. Mid-block is the past: four modest but well-tended whitewashed wooden houses, each with a fenced yard and covered porch. The houses are relics: new construction in wood will be banned on Manhattan in a few years. Reaching high above the attic of the leftmost house is a side-yard tree, possibly the oldest thing in the image.