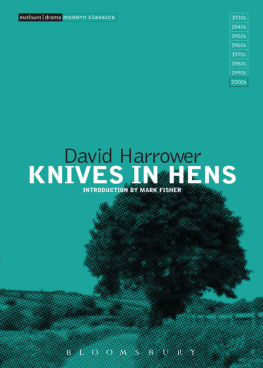

Methuen Drama Modern Classics

The Methuen Drama Modern Plays series has always been at the forefront of modern playwriting and has reflected the most exciting developments in modern drama since 1959. To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Methuen Drama, the series was relaunched in 2009 as Methuen Drama Modern Classics, and continues to offer readers a choice selection of the best modern plays.

A Man for All Seasons

In this tense play of conscience, Thomas More, Lord Chancellor of England, enters into political and moral conflict with King Henry VIII when he refuses to support the Kings move to divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon. Mores decision to endorse the divine right of the Pope over and above that of the King leads to his unwilling martyrdom and tragic downfall.

A Man for All Seasons is an enduring modern classic. It depicts the confrontation between Church and State, theology and politics, absolute power and individual freedom. Throughout the play Sir Thomas Mores eloquence and endurance, his purity, saintliness and tenacity in the face of ever-growing threats to his beliefs, family and life, earn him the status as one of modern dramas greatest tragic heroes.

It is a stark play, sparse in its narrative, sinewy in its writing, which confirms Mr Bolt as a genuine and solid playwright, a force in our awakening theatreDaily Mail

ROBERT BOLT

A Man for All Seasons

A Play of Sir Thomas More

More is a man of an angels wit and singular learning; I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness, and affability? And as time requireth a man of marvellous mirth and pastimes; and sometimes of as sad gravity: a man for all seasons.

Robert Whittinton (1520)

He was the person of the greatest virtue these islands ever produced.

Jonathan Swift (1736)

Robert Bolt (1924-1995) was born at Sale, near Manchester, the son of a shopkeeper. He was educated at Manchester Grammar School and continuing at Manchester University he graduated in history in 1949. He then became a schoolmaster and also started writing radio plays for the BBC before achieving his first London theatrical success with Flowering Cherry (1957).

Bolts reputation rests largely on his historical dramas, all of which involve confrontations of differing values that have altered history. The best of these, A Man for All Seasons (produced at Londons Globe Theatre in 1960 but originally written in 1954 and intended for the radio) deals with Sir Thomas Mores struggle to keep his conscience inviolate while serving his sovereign, King Henry VIII, creating a dramatic clash between principle and power. In Vivat! Vivat Regina! (1970) Bolt returns to the Sixteenth Century, this time examining the confrontation between Elizabeth I and the vividly defiant Mary, Queen of Scots. State of Revolution (1977) depicts the struggle among Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and others to define and implement the Russian Revolution, showing the corrosive effects of dictatorial power on both people and leaders.

In addition to his stage plays, Bolt is equally known for his screenplays, notably Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Dr Zhivago (1966), the Academy Award-winning A Man for All Seasons (1967) which, like the stage productions, starred Paul Scofield, and Ryans Daughter (1969).

The bit of English History which is the background to this play is pretty well known. Henry VIII, who started with everything and squandered it all, who had the physical and mental fortitude to endure a lifetime of gratified greeds, the monstrous baby whom none dared gainsay, is one of the most popular figures in the whole procession. We recognise in him an archetype, one of the champions of our baser nature, and are in him vicariously indulged.

Against him stood the whole edifice of medieval religion, founded on piety, but by then as moneyed, elaborate, heaped high and inflexible as those abbey churches which Henry brought down with such a satisfying and disgraceful crash.

The collision came about like this: While yet a Prince, Henry did not expect to become a King, for he had an elder brother, Arthur. A marriage was made between this Arthur and a Spanish Princess, Catherine, but Arthur presently died. The Royal Houses of Spain and England wished to repair the connection, and the obvious way to do it was to marry the young widow to Henry, now heir in Arthurs place. But Spain and England were Christian Monarchies and Christian law forbade a man to marry his brothers widow.

To be a Christian was to be a Churchman and there was only one Church (though plagued with many heresies) and the Pope was its head. At the request of Christian Spain and Christian England the Pope dispensed with the Christian law forbidding a man to marry his brothers widow, and when in due course Prince Henry ascended the English throne as Henry VIII, Catherine was his Queen.

For some years the marriage was successful; they respected and liked one another, and Henry took his pleasures elsewhere but lightly. However, at length he wished to divorce her.

The motives for such a wish are presumably as confused, inaccessible and helpless in a King as any other man, but here are three which make sense: Catherine had grown increasingly plain and intensely religious; Henry had fallen in love with Anne Boleyn; the Spanish alliance had become unpopular. None of these absolutely necessitated a divorce but there was a fourth that did. Catherine had not been able to provide Henry with a male child and was now presumed barren. There was a daughter, but competent statesmen were unanimous that a Queen on the throne of England was unthinkable. Anne and Henry were confident that between them they could produce a son; but if that son was to be Henrys heir, Anne would have to be Henrys wife.

The Pope was once again approached, this time by England only, and asked to declare the marriage with Catherine null, on the grounds that it contravened the Christian law which forbade marriage with a brothers widow. But Englands insistence that the marriage had been null was now balanced by Spains insistence that it hadnt. And at that moment Spain was well placed to influence the Popes deliberations; Rome, where the Pope lived, had been very thoroughly sacked and occupied by Spanish troops. In addition one imagines a natural disinclination on the part of the Pope to have his powers turned on and off like a tap. At all events, after much ceremonious prevarication, while Henry waited with a rising temper, it became clear that so far as the Pope was concerned, the marriage with Catherine would stand.

To the ferment of a lover and the anxieties of a sovereign Henry now added a bad conscience; and a serious matter it was, for him and those about him.

The Bible, he found, was perfectly clear on such marriages as he had made with Catherine; they were forbidden. And the threatened penalty was exactly what had befallen him, the failure of male heirs. He was in a state of sin. He had been thrust into a state of sin by his father with the active help of the Pope. And the Pope now proposed to keep him in a state of sin. The man who would do that, it began to seem to Henry, had small claim to being the Vicar of God.

And indeed, on looking into the thing really closely, Henry found what various voices had urged for centuries off and on that the supposed Pope was no more than an ordinary Bishop, the Bishop of Rome. This made everything clear and everything possible. If the Pope was not a Pope at all but merely a bishop among bishops, then his special powers as Pope did not exist. In particular of course he had no power to dispense with Gods rulings as revealed in Leviticus 18, but equally important, he had no power to appoint other Bishops; and here an ancient quarrel stirred.

Next page