NUMBER FIFTY-TWO

The Corrie Herring Hooks Series

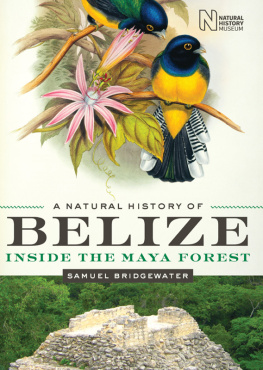

SAMUEL BRIDGEWATER

Foreword by Stephen Blackmore

A NATURAL HISTORY OF

BELIZE

INSIDE THE MAYA FOREST

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS, AUSTIN

in association with the

NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, LONDON

Copyright 2012 by the Natural History Museum, London

All rights reserved

Printed in China

First edition, 2012

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Designed by Lindsay Starr

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bridgewater, Samuel, 1968

A natural history of Belize : inside the Maya forest / Samuel

Bridgewater; foreword by Stephen Blackmore. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The Corrie Herring Hooks series; no. 52)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-72671-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-2927-3900-0 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-73901-7 (individual e-book)

1. Natural historyBelize. 2. Forests and forestryBelize.

3. Land useBelizeHistory. I. Title.

QH108.B43B75 2011

508.7282dc23 2011024357

Dedicated to the memory of Nicodemus (Chapal) Bol (19612011)

FOREWORD

FOR MANY YEARS BIOLOGISTS tended to overlook Belize as a focus of their research and flocked instead to neighboring countries in Central America. During the 1980s, while working for the Natural History Museum in London, I began to get to know Central America through two visits to Honduras collecting herbarium specimens for the international project Flora Mesoamericana. I often heard it said that the most interesting places for biologists in Central America were the Mosquitia region of Honduras, Barro Colorado Island in Panama, and the wonderful national parks of Costa Rica. Belize, in contrast, was not worth visiting because the forests had been destroyed by logging and the impact of frequent hurricanes. What remained, apparently, was uninteresting secondary forest and monotonous swamps.

Fortunately for me, I was persuaded to make a visit to Belize in 1990 by David Sutton, a colleague at the Natural History Museum who knew better. Taking part in the Programme for Belize workshop to develop the management plan for the Rio Bravo Conservation and Management Area swiftly replaced misguided prejudice with a deep impression of an extensively forested country full of wildlife. In a visit of just one week we saw the extraordinary diversity of forest types that are crammed into Belize: pine ridge, rain forest, seasonally dry forests, savanna, and mangrove. The abundance of birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians was remarkable. I was astonished to discover that Belize has the worlds finest zoo and ecotourism facilities of the quality of Chaa Creek and Chan Chich. I met key players from the worlds of government, business, ecotourism, education, and NGOs and could never again fly to Belize without recognizing at least a few old friends at the airport. I found that the history of human occupation of Belize adds layer upon layer of interest to the nature of the country. The density of ancient Mayan sites is extraordinary, although, like everything else in Belize, they are, for no good reason, much less famous than those of Guatemala, Honduras, or Mexico. The diversity of the present-day people of Belize and the warmth of their welcome made a permanent impression. In that week I was hooked. I left feeling that I must have been the victim of a conspiracy of deception intended to keep the place secret. David Sutton was pleased, too. He had utterly convinced me that this was the place for the NHM to establish its proposed tropical field station. The only question was, in a land of so many possibilities, where should it be located?

During our next visit, in 1991, Earl Green, the chief forest officer, and John Howell, the Tropical Forestry Action Plan advisor, suggested that we might do well to build the research station in the Chiquibul Forest. The Chiquibul was then more or less inaccessible, and although it offered the most exciting opportunity of all, it seemed, in every respect, to be beyond our wildest dreams. Attempting to get there in a Forest Department Land Rover proved impossible; we became hopelessly bogged down shortly beyond the Guacamallo Bridge. Undeterred, the decision was made for the Forest Department and the Natural History Museum to build a research station at Las Cuevas. Marcus Matthews was recruited to lead the project, ably supported by Nicodemus Chapal Bol and his wife, Celia. My first night at Las Cuevas was at the end of the second Joint Services Expedition to the Upper Raspaculo River in 1993. The excitement of exploring the forest and caves, together with the chorus of frogs, made it impossible to sleep. Thanks to extraordinary support from the British Forces, the research station was grander than we could have imagined and soon established itself as a superb base for research and conservation projects. Later, John Howell came out of retirement to head up Las Cuevas Research Station, and he was followed in turn by Chris Minty, who was awarded an MBE for his work there, and Sam Bridgewater.

Today Las Cuevas is thriving under the leadership of Chapal and is managed, as it should be, by the Las Cuevas Trust, a Belizean NGO. Scientists from the NHM continue to be involved, but now a cluster of international organizations, including the Conservation Management Institute of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Acadia University, and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh work alongside the University of Belize, Friends for Conservation and Development, and the Belize Forest Department to keep Las Cuevas thriving. When I last visited Belize, in 2004, I was delighted to hear several representatives of the Belize government say what a significant part the station had played in the conservation of the Chiquibul Forest. The accumulated scientific papers and reports testify to the importance of the Chiquibul and Belize. But until the publication of this new book there has been no synthesis of the biodiversity and ecology of what is now, at long last, properly recognized as one of the most significant centers of biodiversity in Central America. Thanks to Sam Bridgewater, the secret is now out!

Professor Stephen Blackmore,

Regius Keeper, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK COULD NOT HAVE BEEN WRITTEN without the help of a great many people. First and foremost are the staff members of Las Cuevas Research Station, who have kept the facility operational over the years despite considerable financial and logistical challenges. Particular thanks are due to Nicodemus (Chapal) and Celia Bol, who have been the heart and soul of the station, always providing a warm welcome to visitors, keeping them safe, and catering tirelessly to their needs. Chapals tragic death in 2011 is a great loss to the facility. His love of, respect for, and knowledge of the jungle made him uniquely adapted to the position of Operations Manager and, subsequently, Station Manager. With him, the station and the Chiquibul forest have lost their staunchest supporter and a tireless campaigner.

The books foundation is the science of the researchers who have visited the facility over the years, and it is hoped that the contents does justice to their endeavors. The author takes responsibility should there be any misrepresentation of their research findings. The science underpinning the book is credited to the original authors through endnotes. Numerous individuals have provided photographs for the book and are credited alongside their images.

Next page