Dramatic Exchanges

The Lives & Letters of theNational Theatre

Dramatic Exchanges

The Lives & Letters of theNational Theatre

Selected and edited by

Daniel Rosenthal

For Lyn Haill and Gavin Clarke

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Introduction, Selection, Commentary and Sources copyright Daniel Rosenthal 2018

Copyright material owned by the National Theatre National Theatre

All rights in third party copyright material quoted in this book are reserved to the individual copyright holder. Full copyright acknowledgements appear on , which for copyright purposes are an extension of this page.

The right of Daniel Rosenthal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

All reasonable efforts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if notified in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9781781259351

EISBN 9781782833970

Text design and layout by Nicky Barneby

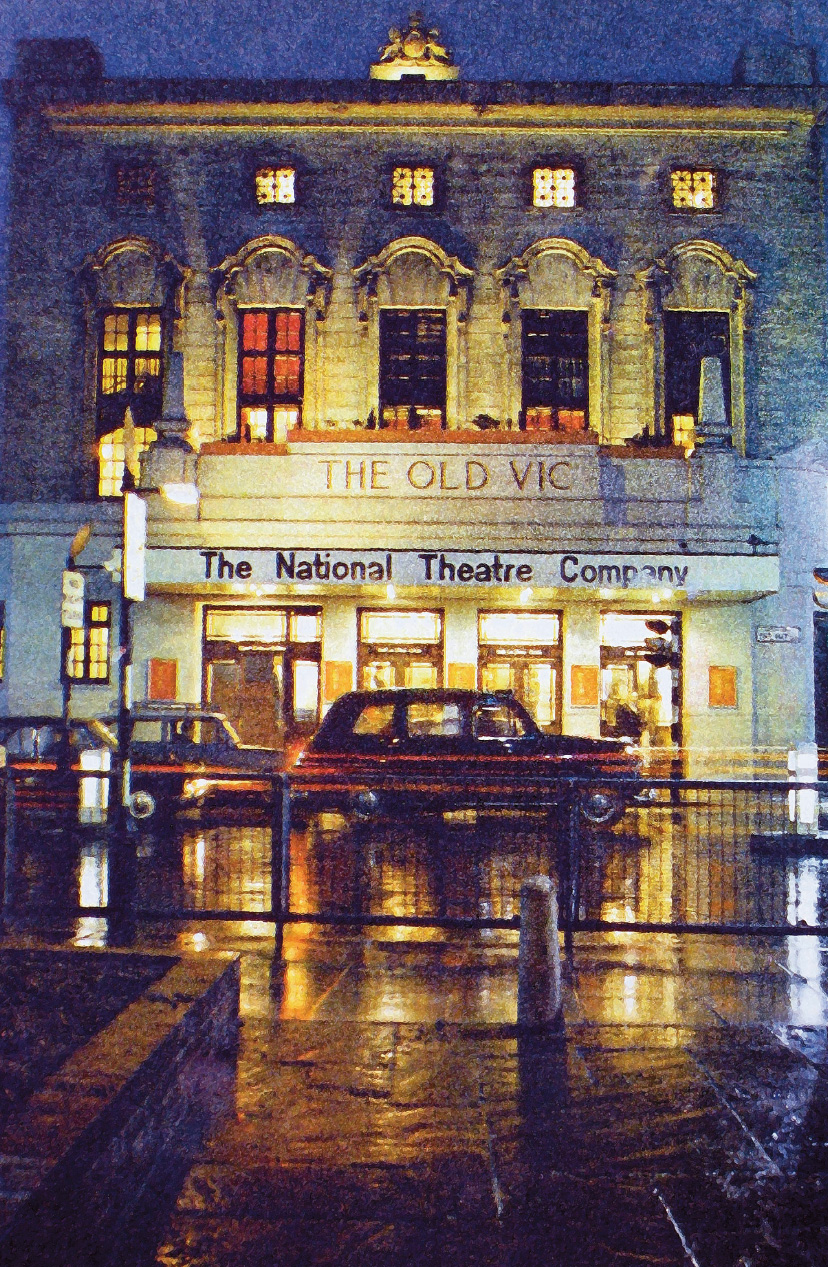

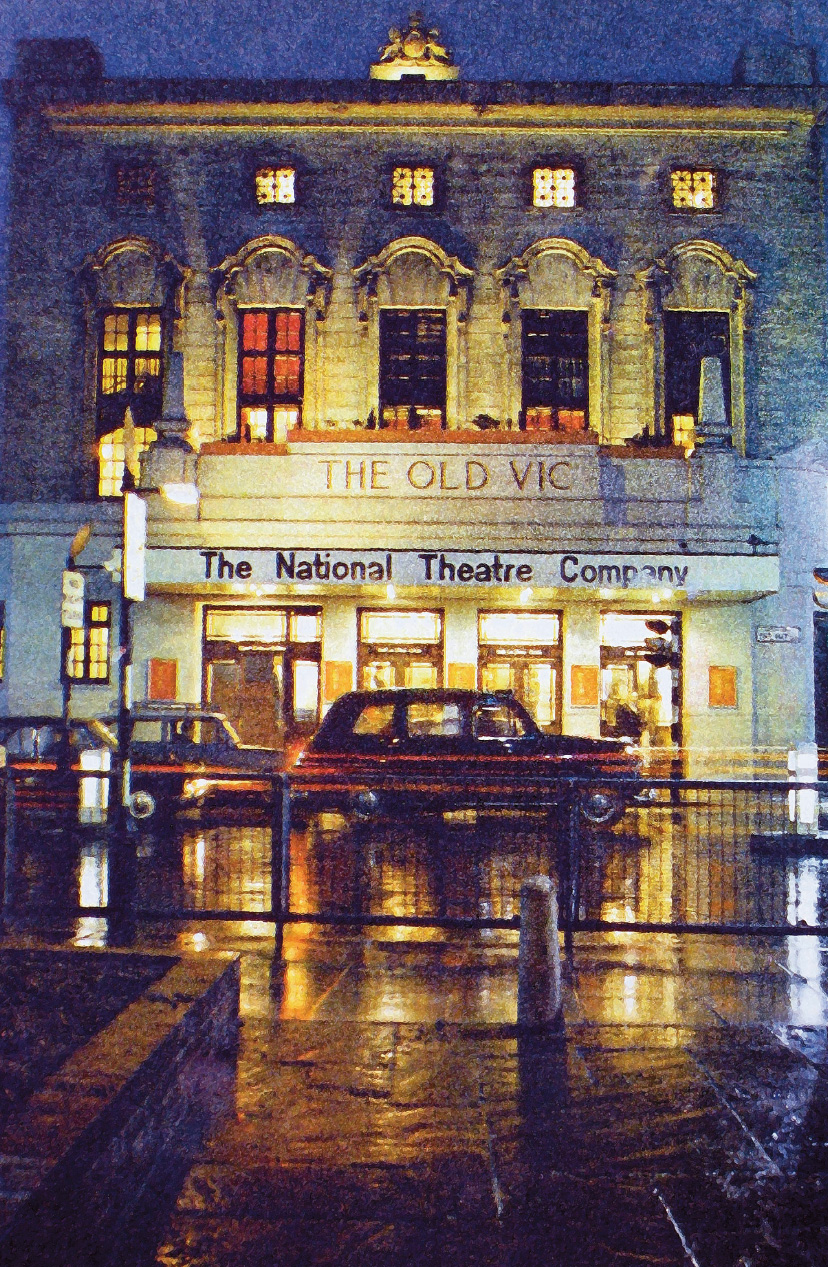

Photograph before title page: The Old Vic in the 1960s. It was home to the National Theatre Company from 1963 to 1976. Photo: Chris Arthur

Contents

Helen Mirren rehearsing the title role of Phdre, 2009. Photo: Catherine Ashmore

Foreword

What this book shows is that letters have the power to transport us, just as theatre does. Many of us have a stash of envelopes somewhere, containing letters that tell love stories, crack open secrets or rekindle old memories. Similarly, the correspondence in these pages gives us access to privileged information that ignites curiosity the impression is sometimes of peeking around a curtain when one shouldnt. Yet, while many of these letters were originally intended for private consumption, they tell a story that in some ways belongs to us after all, the National Theatre is publicly funded; its history and legacy are for us all.

This correspondence is part of an actors life, as much as the letters, and now emails, discussing scripts or offering roles. Dramatic Exchanges brings together hundreds of these missives, and offers a thrilling insight into other peoples lives and creative practices. Its fascinating to read the correspondence behind plays Ive watched and loved, and particularly to read letters from actors, writers and directors with whom Ive worked, such as Richard Eyre, Nick Hytner, Peter Brook, Michael Gambon and Ian McKellen.

For many years, I was a member of the audience at the National Theatre, rather than a player on its stages. Among many other plays, I remember watching The Recruiting Officer and Othello, both with Laurence Olivier, in the Old Vic and later The Royal Hunt of the Sun on the South Bank. I have sat amid the expectant pre-show hubbub in the Dorfman, Lyttelton and Olivier, waiting for the lights to dim and the magic to start. Over the years I visited friends in their dressing rooms, where postcards, telegrams and notes wishing them well fringed their mirrors.

In the 1970s I became involved in the larger story of the NT through a letter I wrote to the Guardian about overspending in theatres my follow-up letter to Lord Birkett is included here, and several of the points I made then remain close to my heart, among them the closure of regional theatres, which is still an ongoing problem today, and the lack of inclusiveness which affects both theatregoers and performers.

But the NT itself has changed, and there is a range of programmes from 15 tickets to EntryPass for 1625-year-olds, to NT Live designed to help open its productions to a wider audience, keeping the art of the theatre alive and relevant.

In 2009, eleven years after my debut at the National, I was honoured to be involved in the very first NT Live broadcast, playing the title role in Phdre. That night, our performance in the Lyttelton was broadcast live to 72 cinemas around the country; faced by an audience of around 800 in the auditorium, we were suddenly performing to many thousands of people.

Dramatic Exchanges effects a comparable expansion in the audience for these letters: often intended for an intimate audience of one, they may now be read by us all. Its illuminating to discover how my contemporaries and predecessors have grappled with some of the big questions of our craft during the first 55 years of the Nationals production history and exciting to wonder what is now being said over email, what groundbreaking NT projects are in development, and how the next half-century will play out. Whatever happens, though, I doubt if well ever stop sending cards on opening night.

Helen Mirren

July 2018

Introduction

In 1981, the dramatist Peter Shaffer and director Peter Hall exchanged letters concerning Halls discovery that, having triumphantly staged Shaffers Amadeus at the National and on Broadway, he would be denied the chance to direct it for the screen. Shaffers remorse at this turn of events was matched only by Halls disappointment, anger and indignation.

At the NT Archive more than 20 years later I read this exchange, in which Shaffer curses his own hesitation and drift, and Hall accuses him of cowardly and appalling behaviour. It was my first close encounter with the power of theatrical correspondence, and the inspiration for the book you now hold (Shaffer and Halls letters appear on pp. 17071). I was used to actors, directors and playwrights expressing themselves forcefully in biographies or memoirs, in newspaper and on-stage interviews, but in gathering correspondence for this book I discovered that the raw, unmediated candour of private letters, in which practitioners attempt to reconcile the demands of art, commerce, friendship and ambition, is more affecting and revealing.

On Amadeus, the (temporary) souring of Shaffer and Halls professional collaboration pushed them to expressions one might otherwise expect only in love letters. And much of the correspondence in this volume shows actors, designers, directors, literary managers, playwrights and stage managers experiencing, and articulating, intense emotions (a passionately committed Helen Mirren; joyful Judi Dench and James Corden), sometimes confirming, sometimes contradicting carefully honed personae: John Osborne, writing back in anger; Laurence Olivier, sometimes flattering, sometimes wounding, always florid; Alan Bennett, a study in self-deprecation.

Next page