The Myth of Continents

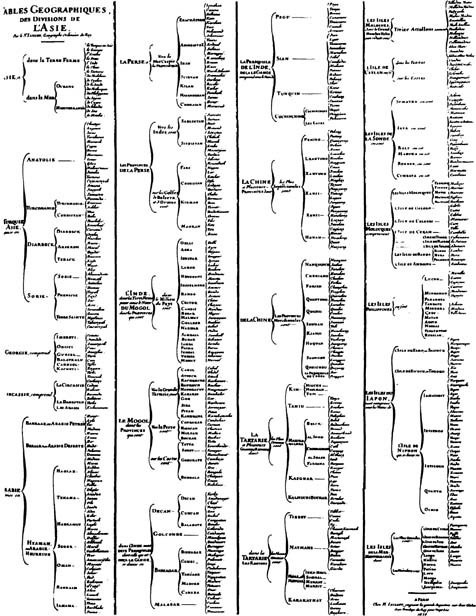

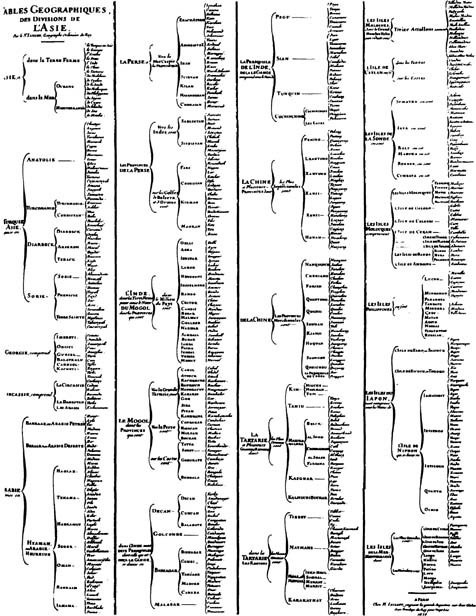

Nicolas Sansons Geographical Divisions of Asia, 1674. (Courtesy of State Historical Society of Wisconsin.)

The Myth

of Continents

A Critique of Metageography

Martin W. Lewis

Kren E. Wigen

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

1997 by

The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lewis, Martin W.

The myth of continents : a critique of metageography / Martin W. Lewis, Kren E. Wigen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographic references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-20743-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Geographical perception. I. Wigen, Kren, 1958 . II. Title.

G71.5.L48 1997

Printed in the United States of America

11 10 09 08 07

12 11 10 9 8

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Maps

Preface

Foreign Minister Gareth Evans was determined to put Australia on the map. Literally. He arrived in Brunei in late July for talks centered around the annual ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] foreign ministers meeting armed with a new map depicting the land Down Under as smack in the heart of the East Asian hemisphere.

The persuasive diplomat failed to convert everyone to his world view, however. If I look at a map, I will immediately say that Australia is not part of Asia, Malaysias Foreign Minister Datuk Abdullah Ahmad Badawi said under questioning from Australian journalists. Tou dont know your geography.

Murray Hiebert

Every global consideration of human affairs deploys a metageography, whether acknowledged or not. By metageography we mean the set of spatial structures through which people order their knowledge of the world: the often unconscious frameworks that organize studies of history, sociology, anthropology, economics, political science, or even natural history. This book has been written in the belief that a thorough examination of these frameworks is long overdue.

With the end of the Cold War, popular conceptions of global geography in the English-speaking world have grown ever more tenuous and uncertain, and standard methods of organizing and classifying spatial phenomena no longer seem adequate for the task. During the period of Cold War rivalry, Americans relied heavily on a tripartite divisional scheme to now, however, the communist Second World has all but collapsed, and comfortable distinctions between First and Third Worlds are being shaken by differential rates of economic growth. In the case of continents, which educated Europeans have taken for centuries as forming the earths fundamental geographical structure, the erosion of confidence is more subtle; today we still employ continental divisions but with increasing uneasiness about where they lie and what they signify. The notion of world regions or areas is also under siege. Scholars grew accustomed in the 1960s and 1970s to organizing their investigations of the globe around the area studies concept; now, they find the salience of world areas called into question, as funding agencies threaten to withdraw support from area-focused research. Even the nation-state, which had acquired the status of a foundational and seemingly permanent territorial entity, suddenly appears vulnerable; cartographers have had to revise the basic political map of the world several times since 1989. But perhaps most problematic of all is our simplest, highest-order geographical concept, distinguishing something called the West from the rest of the world. While this terminology continues to be used even by its critics, the notion of dividing the globe in this way has been loudlyand incontestablydenounced as bigoted and distorting.

While the resulting crisis in conceptualization has yet to be fully acknowledged, various groups are already proposing new ways of cutting up the world, competing to come up with more appropriate geographical categories for the twenty-first century. As yet, however, there is no clear consensus about how to proceed. Many writers replace the paradigm of First, Second, and Third Worlds with a bipolar scheme, opposing a wealthy North to an impoverished South. But the use of these terms is neither precise nor consistent; as recently as 1991, a gathering of scholars concerned with geopolitics rather than social development deployed the category Northwithout commentto refer to the former Soviet Union and its onetime allies.

As this last example suggests, even as new proposals are being floated,

Whatever their differences, all of these approaches share one attribute: a profound skepticism toward received metageographical constructs.division have proved remarkably tenacious, even among those who are trying to shake them off. Moreover, while it may be increasingly recognized that particular concepts are inadequate, the problem has only been addressed in an ad hoc and piecemeal fashion; metageography as a system has yet to emerge as a topic of sustained intellectual discussion and debate. In the absence of a systematic and forceful effort to expose their inadequacies and to replace them with something better, the old geographical concepts continue to hold our imagination in thrall.

If metageography has not been prominent on the national agenda, one important cause lies in the institutional weakness of geography as a discipline. The neglect of geography in this country is so pervasive that the crumbling of our global geographical concepts is obscured by sheer geographical illiteracy.

Students are not entirely to blame. Most college-aged Americans have never explicitly studied geography, since most primary and secondary schools discontinued teaching the subject in the 1960s on the theory that memorization would stultify young minds. The sorry results of this misguided experiment are now fully evident, and broad-based efforts at reform are under way. Thanks in part to the National Geographical Society and the Association of American Geographers, basic geographical education is gradually returning to American elementary and high schools. Parents also seem to be responding, and cartographic toys and games now form a minor growth industry. At the university level, however, the situation remains grim. Geography is a marginalized discipline, absent from many of this countrys top-ranked universities and threatened at others. In consequence, the need to reconceive our basic vision of world geography comes at a time when geography as an academic discipline lacks the institutional support to respond effectively.

Next page