Olsen - Archaeology the discipline of things

Here you can read online Olsen - Archaeology the discipline of things full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Berkeley, year: 2012, publisher: University of California Press, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Archaeology the discipline of things

- Author:

- Publisher:University of California Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- City:Berkeley

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Archaeology the discipline of things: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Archaeology the discipline of things" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Olsen: author's other books

Who wrote Archaeology the discipline of things? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Archaeology the discipline of things — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Archaeology the discipline of things" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Caring about Things

This book is about archaeology and things. It considers the ways in which archaeologists deal with things, how they articulate and engage with them. The book offers a series of snapshots of archaeology as design and craft; archaeology is proposed as an ecology of practices, tacit and mundane, rich and nuanced, that work on material pasts in the present. We argue that a mark of archaeology is its particular kind of care, obligation, and loyalty to things. Our purpose in this introduction is to specify why archaeology should carry the moniker of the discipline of things.

There is a growing litany of academic fields that now place emphasis on object-oriented approaches, taking things, their objecthood and materiality, seriously (Bennett 2010; Brown 2003; Bryant, Srnicek, and Harman 2010; DeLanda 2006; Domanska 2006a and b; Harman 2002, 2009a and 2011; Henare, Holbraad and Wastell 2007; Latour 2005; Latour and Weibal 2005; Preda 1999). It would certainly be disingenuous fully to disassociate ourselves from such academic kinetics, yet our novelty of purpose lies in revisiting, articulating, and developing what archaeologists have always done since the days of antiquarian science, and to emphasize how much archaeology brings to this new focus on things. Indeed, we even argue that archaeology offers an essential grounding to this ontological turn. This point is strangely absent from what is an increasingly pressing transdisciplinary discussion (cf. Latour This is not to say that archaeologists are not undertaking work that engages with the discussion (see, e.g., Alberti and Bray 2009; Alberti et al. 2011; Brown and Walker 2008; DeMarrais, Gosden, and Renfrew 2004; Harrison and Schofield 2010; Gonzlez-Ruibal 2008; Gonzlez-Ruibal, Hernando, and Politis 2011; Hodder 2011; Jones 2007; Knappett 2005; Knappett and Malafouris 2009; Lucas 2012; Meskell 2005; Olivier 2008; Olsen 2003 and 2010; Schiffer with Miller 1999; Walker 2008; Webmoor and Witmore 2008; Witmore 2004b; see also contributions to Hicks and Beaudry 2010). However, it is quite appropriate to suggest that archaeology is most often caricatured by other fields of endeavor as a circumscribed set of technical practices and interests that bear only indirectly upon the key terms of debate taken up in the ontological turn to things. On the other hand, archaeologists have not been as vocal as they could be in correcting such a view. There is an old and deeply rooted inferiority complex among some archaeologists, encapsulated in a self-image of archaeology as a second-rate, social science. This is often accompanied by an embarrassment that archaeology studies just things, in contrast to the supposed cultural richness and subjective presence of text and voice. There is also even outright ambivalence and obscurity concerning the character and scope of archaeological practices.

We are far more optimistic. Indeed, we would go so far as to suggest that archaeology has developed an extended historiographical scope over the past few decades, offering a much broader scope than history itself (consider Foucaults use of the terms archaeology [1972, 1973] and genealogy [1977, 1984]). Archaeology encompasses the mundane and the material; its work is the tangible mediation of past and present, of people and their cultural fabric, of the tacit, indeed, the ineffable. It is this broad ecology of practices that we seek to understand better.

One can read the notion that archaeology is the discipline of things in many ways. Our own reading is deeply practical; that is, centered upon what it is that archaeologists do. When one contemplates the hundreds of labor hours spent measuring, plotting, and drawing scenes on Corinthian perfume jars (aryballoi) by a practitioner interested in the development of ceramic design; when one considers the thousands of photographs deployed in documenting the excavations at Hissarlik in the waning decades of the nineteenth century, it seems trivial for an archaeologist to underline the point that words cannot provide an adequate expression for the ways the world actually exists. Words alone fail us with respect to matters of ontology. Therefore, we maintain also an elliptical drive to the expression archaeology is the discipline of things, because we are not seeking to hammer out a fixed meaning.

The proposition that archaeology is the discipline of things does carry both rhetorical and etymological weight. Rhetorical, because in looking for the Indian behind the artifact, many archaeologists (but by no means all), whether through embarrassment or an urge to engage with vanguard intellectual debates, have disregarded and ultimately forgotten the very thing they know bestthings (Olsen 2003; 2010). Etymological, because one may translate ta archaia, one of the two components of the word archaeology, literally as old things. Put this together with the second component of the word, logos, and one might speak of the science of old things. Of course, the question of what both these components are is by no means straightforward (consider Shanks and Tilley 1992).

Practically speaking, the empirical fidelity of archaeology has always been to (old) things: Corinthian aryballoi, former Roman fortifications, avenues at Teotihuacan, abandoned Soviet mining towns, Smi hearths, and mud bricks. As an empirical science, archaeology is concerned with the elucidation and analytic observation of immediate experience within which things play myriad roles, as do practitioners. These concerns play out across an iterative process of engagement and manifestation shaped by commitments to accuracy and adequacy of articulation and expression. Every science, as Alfred North Whitehead phrased it, must devise its own instruments (1978 [1929], 11). It has been in this very regard that archaeology has often labeled itself as a secondary science (applied or derivative), one that adds the products of forerunner disciplines and sciences (such as math and physics) to their accounts of the past (see, e.g., Nichols, Joyce, and Gillespie 2003).

However, the adjective secondary is not a scarlet letter of shame. Many of the so-called secondary sciences (e.g., education or nursing) are, in fact, sciences of care (Mol 2008). And here, we may draw a contrast with the heroic and lofty pursuit of the natural sciences (within archaeology, consider Gero and Conkey 1991). While not all archaeologists share similar perspectives, and neither do they necessarily share similar practices, there is nevertheless common groundthings draw the discipline together. Here we come closer to our reading of the discipline of things in the practical sense, that is, in terms of what it is that we do as archaeologists. From this angle, the phrase discipline of things underlines what is foremost a feeling of care and concern for legion material entities, from the monumental to the utterly mundane. Equally this moniker refers to how things themselves are lures for feeling, as Alfred North Whitehead put it (1978 [1929], 87). We aim to place intuition, emotional allure and tacit engagement with things on the same footing as any intellectual rationale for the discipline.

Given the humanistic framing of so many archaeological endeavors, the notion of archaeology as secondary science is inadequate. From the big stories of urban development, the role of humanity in environmental change, or the rise of distinctive forms of complex polity, to the incidental details of animal figures in Scandinavian rock art, stems of clay smoking pipes, or the morphology of a human/bull cooking pot, archaeology has long delivered messages, whether analytical, critical, and/or speculative, that relate to the core of the human condition. It is also these big and small stories that make archaeology one of the most popular of the human and social sciences when it comes to public outreach and appeal.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

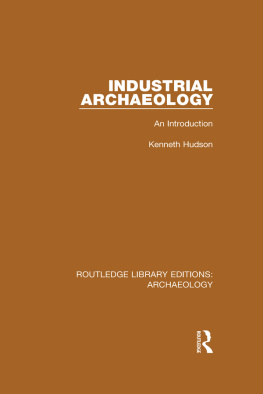

Similar books «Archaeology the discipline of things»

Look at similar books to Archaeology the discipline of things. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Archaeology the discipline of things and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.