Copyright

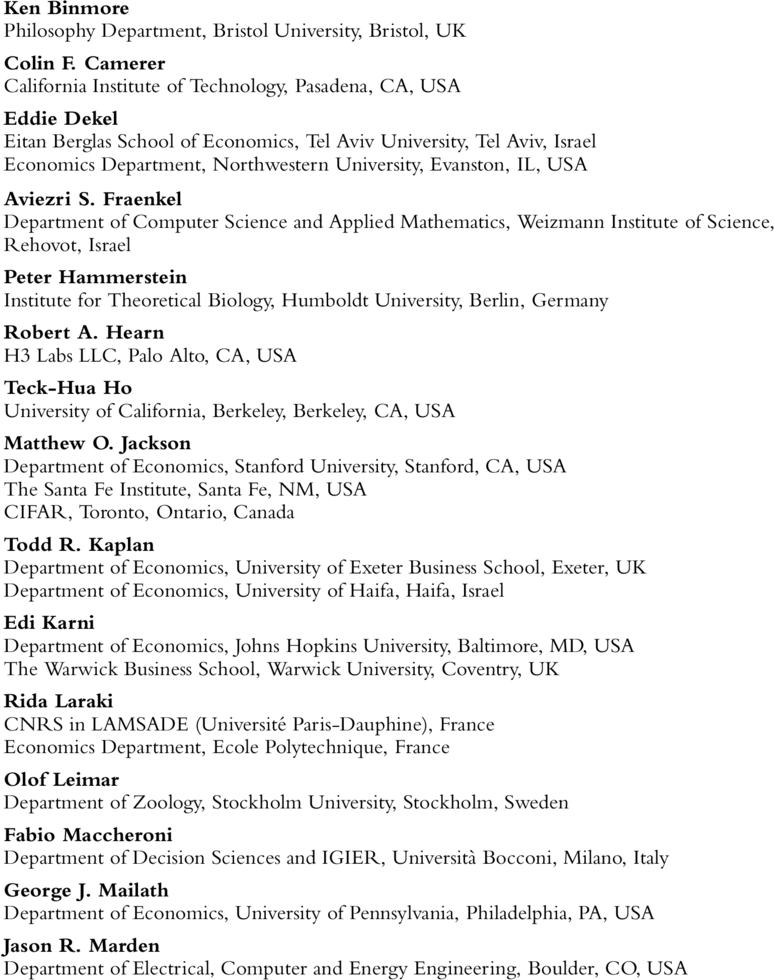

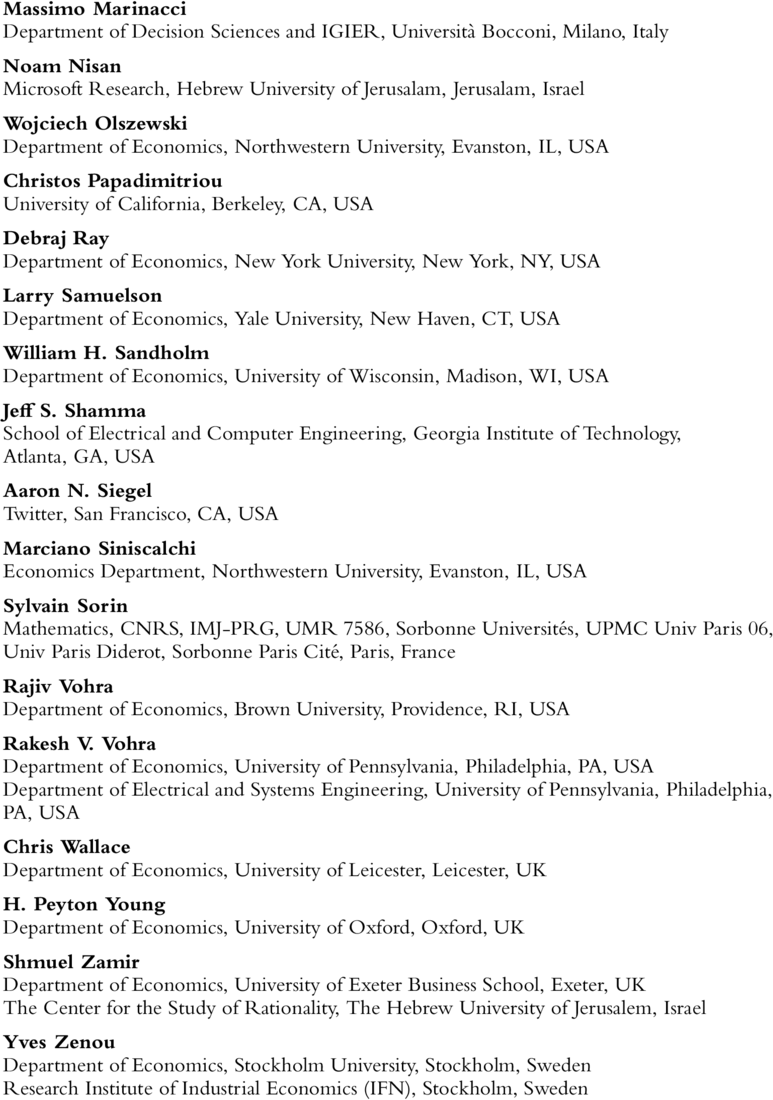

Contributors

Preface

H. Peyton Young Shmuel Zamir Over a decade has passed since the publication of the previous volume in this series. In the interim game theory has progressed at a remarkable rate. Topics that were merely in their infancy have become well-established; others that had reached maturity have expanded so much that they warrant a fresh treatment. The former category includes games on networks (. There have been several other important developments.

One is the blurring oflines between cooperative and noncooperative game theory. For example, games played on networks, the dynamics of coalition formation, and applications of game theory to computer science use a combination of noncooperative and cooperative techniques. Another important development is the rapid expansion of game theory into fields outside of economics. These include computer science (). Game theory has also found an increasing number ofapplications, such as the design of matching markets, auctions, utility markets, internet protocols, and many others. For this reason the present volume bears the title The Handbook of Game Theory , in contrast to the earlier three volumes, which were called Handbook of Game Theory with Economic Applications.

The chapters are intended to provide authoritative introductions to the current literature at a level accessible to students and nonspecialists. Contributors were urged to provide their own perspective as opposed to an encyclopedic review of the literature. We also urged them to draw attention to unsolved problems and alternative perspectives. The result is a set of chapters that are more diverse in style than is typical for review articles. We hope that they succeed in drawing readers into the subject and encourage them to extend the frontiers of this extraordinarily vibrant field of research.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Scott Bentley, Joslyn Chaiprasert-Paguio, PaulineWilkinson, and the production team at Elsevier for bringing this volume to fruition.

We are particularly indebted to Romina Goldman, who provided us with invaluable assistance throughout the process and helped keep the trains running on time.

Introduction to the Series

Kenneth J. Arrow; Michael D. Intriligator The aim of the Handbooks in Economics series is to produce handbooks for various branches of economics, each of which is a definitive source, reference, and teaching supplement for use by professional researchers and advanced graduate students. Each handbook provides self-contained surveys of the current state of a branch of economics in the form of chapters prepared by leading specialists on various aspects of this branch of economics. These surveys summarize not only received results but also newer developments, from recent journal articles and discussion papers.

Some original material is also included, but the main goal is to provide comprehensive and accessible surveys. The handbooks are intended to provide not only useful reference volumes for professional collections but also possible supplementary readings for advanced courses for graduate students in economics.

Chapter 1

Rationality

* Philosophy Department, Bristol University, Bristol BS8 1TB, UK

Abstract

This chapter is a very compressed review of the neoclassical orthodoxy on the nature of rationality on economic theory. It defends the orthodoxy both against the behavioral criticism that it assumes too much and the revisionist view that it assumes too little. In places, especially on the subject of Bayesianism, the paper criticizes current practice on the grounds that it has gone astray in departing from the principles of its founding fathers. Elsewhere, especially on the modeling of knowledge, some new proposals are made.

In particular, it is argued that interpreting counterfactuals is not part of the function of a definition of rationality. Keywords Substantive rationality Neoclassical economics Revealed preference Risk Uncertainty Bayesianism Small worlds Common prior Common knowledge Nash equilibrium Equilibrium selection Refinement theory Nash program JEL Codes B41 C70

1.1 Neoclassical Rationality

The Oxford Handbook of Rationality () contains 22 essays with at least 22 opinions on how rationality can or should be construed. None of these views come anywhere near the strict neoclassical orthodoxy to which this article is devotedeven when the authors imagine they are discussing rationality as understood in economics. Would the authors have done better to abandon their various rationality models in favor of the neoclasssical orthodoxy? I think it would be a bad mistake to do so in the metaphysical belief that the neoclasssical orthodoxy is the one and only true model of rationality. The best that one can reasonably hope for in a model is that it should work well in a properly defined context. On this criterion, the neoclasssical orthodoxy continues to be hugely successful when applied in the kind of economic context for which it was created.

However, this article argues that the economics profession is suffering from all kinds of indigestion as a result of being too ready to swallow various attempts to extend the orthodoxy to contexts for which it is not suited. For such purposes, we need new models of rationalitynot to replace the current orthodoxy but to take over in contexts for which the current orthodoxy is ill-adapted. In brief, one may not like the 22 rationality models of the Oxford handbook any more than I do, but there is no reason to think that their authors are wasting their time in contemplating alternatives to the neoclassical orthodoxy.

1.1.1 Substantive or procedural?

One limitation of the neoclassical orthodoxy is that it is a theory of substantive rationality rather than procedural or algorithmic rationality (). That is to say, the orthodoxy is concerned only with what decisions are made and not with how they are made. But what hope is there of predicting what errors economic agents are likely to make in practice without some theory of how their minds work? For this reason, some behavioral economists advocate abandoning the neoclassical orthodoxy in favor of empirically based theories of bounded rationality.

Nobody denies that scientific theories of bounded or algorithmic rationality are much to be desired, but even if such theories became more firmly established than at present, the example of evolutionary biology explains why it does not follow that it would be wise to abandon the neoclassical orthodoxy.

1.1.1.1 Evolution

Evolutionary biology is perhaps the application in which game theory has had its greatest successes, sometimes predicting the behavior of animals in simple situations with considerable accuracy. But none of these successes have been achieved by tracking what goes on inside the heads of the players of biological games. Biologists speak of proximate causes when they explain behavior in terms of enzymes catalyzing chemical reactions or electrical impulses propagating through neurons. However, such proximate chains of causation are usually leapfrogged in favor of ultimate causes, which assume that evolution will somehow create internal processes that lead the players to act as though seeking to maximize their expected Darwinian fitness. The end-products of impossibly complicated evolutionary processes are thereby predicted by assuming that they will result in animals playing their games of life in a rational way.