Table of Contents

For Spence,

who would have dug it

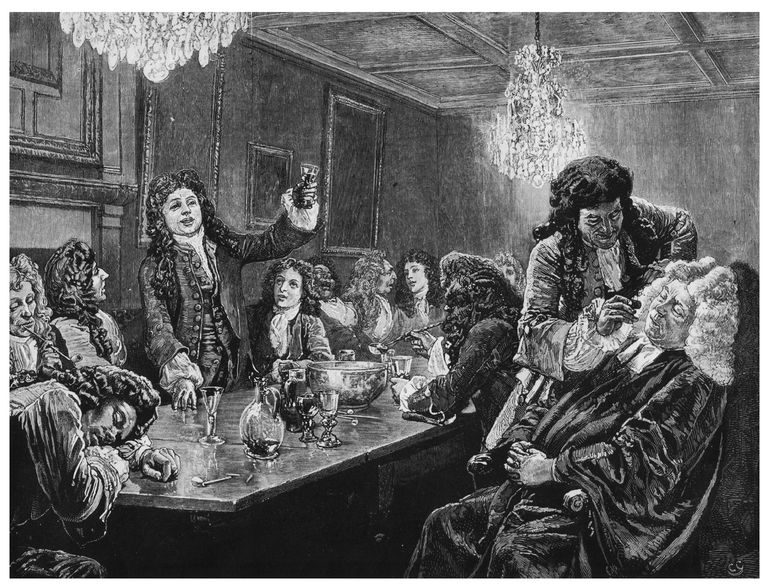

The Age of Punch as seen by its grandsons

AUTHORS COLLECTION

INVOCATION

In the Age of Chaos, long before the creation of the Cocktail, Spirituous and Aqueous, Thick and Thin, Sweet and Sharp and Unctuous were all tumbled together in One Undifferentiated Mass without Form or Order. Then from the East there rose a Sun to dry the Wet and distill the Light from the Heavy. And then all Drinks began to know their Proper Kinds and submit the Willfulness of their Doing to the Correction of Just Reason. That Sun had a Name, and that Name was Punch.

PREFACE

This book is about Punch. And by Punch, I dont mean the stuff sluiced around at fraternity mixersseveral 1.75-liter handles of whatever hooch is the cheapest, diluted with a random array of sodas and ersatz juices and ladled elegantly forth from a plastic trash can. Nor do I mean the creative concoctions proffered by feature articles on stylish entertaininglight, colorful things that are all fizz and fruit and are far too eager to please to be taken seriously as a delivery system for beverage alcohol.

In short, there are lots of punches this book isnt about. But you wouldnt expect a serious book on the Martini (such things do exist) to waste a lot of time on the so-called Chocolate Martini or, in fact, on anything not containing gin, vermouth and practically nothing else that tries to pass itself off as a Martinito say nothing of the x-tini, where x Mar. And this is a serious book about Punchwell, as serious as a book can be that tells the story of a means of communal inebriation and its associated traditions, supported by a slew of sometimes rather fiddly formulae for re-creating drinks that havent been tasted by humankind in at least a century and a half. In any case, its the first of its kind, and as such, its going to discriminate.

The fact that nobodys published a real book about Punch before is in and of itself a remarkable thing. Open just about any volume written in English between the late 1600s and the mid 1800s that deals with the details of day-to-day life and odds are sooner or later somebodys going to brew up a bowl of the stuffBehn, Defoe, Addison and Steele, Swift, Pope, Fielding, Richardson, Smollett, Sheridan, Boswell, Burney, Edgeworth, Austen, Coleridge, Byron, Thackeray, Dickens, world without end. The rakes of the Restoration knew it, William and Marys subjects drank it readily, the reigns of the three Georges were damp with itvery dampand the Regency was well steeped indeed. George Washington enjoyed it, and Thomas Jefferson owed a part of his property to it. For some two hundred years, Punchat base a simple combination of distilled spirits, citrus juice, sugar, water and a little spicewas the reigning monarch of the kingdom of mixed drinks. If nothing else, it has stories to tell.

Most of Punchs stories are of warm fellowship and conviviality and high-spirited gatherings afloat on oceans of witty talk. But it would be disingenuous to pretend that there arent also plenty of battles and brawls and all the other products of the temporary madness that overtakes even the strongest-headed when theyve consumed more distilled spirits than they can keep track of. For every cozy evening like the ones the settled Sussex townsman and diarist Thomas Turner used to spend, back in the days of George III, drinking Punch made from smuggled French brandy with his fellow tradesmen, there was one like Captain Drakes in early 1709, when he sat up guzzling Arrack Punch with three fashionable whores in his cell in Londons Newgate Prison, where he was being held for treason under arms. On a sudden some difference arose between the ladies, he later recalled, causing them to engage in bloodshed and battery until they were exhausted and their clothes and coiffures in tattersat which point they patched themselves up as best they could, rearranged their hair, and called for another bowl.

But sufficient as it may be, the chance to retail a few drams of damp anecdotes is far from the only reason to write a book about Punch. Recent years have seen public interest in the fine art of mixing drinks fizz up to an almost alarming level, spawning a number of surprisingly sober books on the subjectbooks that focus almost obsessively on the craft and history of the Cocktail. (I myself have written three.) Almost without exception, these books have focused on the American part of the storythe part that begins with the Sling, the Cocktail, the Mint Julep and all the other ancestral American sensations, progenitors of pretty much every mixed drink we lap up today save Vodka and Red Bull, and you could even squeeze that one in among the Slings if you were to rub it with a little Vaseline first.

We dont know who first came up with the Julep or the Cocktail or indeed almost any of the foundational American drinks. But somebody had to teach those anonymous folk geniuses how to mix drinks. Mixology might be simple enough, as far as crafts go, but it still has its secrets, its right ways and wrong ways, its tricks and traditions. Indeed, by 1806, when the Cocktail was first defined in print, concerned men and women had been grappling for two centuries and more with all the issues of balance, potency and proper service that mixing drinks with distilled spirits raises. Admittedly, in the larger scheme of things, these are pretty trivialunless, that is, youve just laid down good coin for a drink, coin that was earned by the sweat of your brow (or whatever other part of your body you sweat with). In that case, it has real meaning whether the drink youre about to taste was assembled by a ham-handed ignoramus whos making it up as he goes along or by someone who has spent a few years absorbing the best practices of the job from people who really know their onions.

In the early days of the American republic, when this quintessentially American art was first finding its legs, the best practices with which the wide-awake young men behind the bar had been indoctrinated were British, developed across the Atlantic and transplanted in American soil, and the laboratory in which they had been developed was the Punch bowl. We dont know precisely who invented Punch in the first place, nor are we ever likely to. But we dont know who invented the Martini, either, or the original Cocktail. Such is the history of mixed drinks. We do know that if Punch wasnt the first mixed drink powered by distilled spirits, it was certainly the first globally popular onespirits-drinkings killer app, as it wereand that its first unambiguous appearance in writing was in a letter by an Englishman. Whoever might have invented it, it was Englishmen, or at least Britons, who fostered the formula, spread it to their neighbors, took it all around the world.

Although when I say Englishmen, I am doing a great injustice, as much if not most of the mixing of drinks that was done in England in the eighteenth century was not done by men at all. Bartending was a womans job. Thats not to say that no men ever performed it, but the standard setup was the man as proprietor, host, bouncer and business manager, while the ones who drew the drinks and served them were femalein fact, they were often the proprietors daughters, the prettier the better. As Thomas Brown observed in 1700, Every Coffee-House is illuminated both without and within Doors; without by a fine Glass Lanthorn, and within by a Woman... light and splendid, whose job was not only to serve the customer but to chaff him and flirt with him and draw him in. I suspect that the freedom the modern bartender possesses to banter with a customer, a thing not common in the service professions, was fought for and won by those Punch-slinging young barmaids of three hundred years ago.