1.1 The Three Pillar Approach

Recent years have shown that (financial) companies need to have a good executive board, a good business strategy, a good financial strength and a sound risk management practice in order to survive financial distress periods. It is essential that the risks are known, assessed, controlled and, whenever possible, quantified and mitigated by the management and the respective specialized units.

Especially in the past few years, we have observed several failures of financial companies (for example, Barings Bank, HIH Insurance Australia, Lehman Brothers, Washington Mutual, etc.). Many companies have faced severe solvency and liquidity problems. As a consequence, supervision and politics have started several initiatives to analyze these problems and to improve qualitative and quantitative risk management within the companies (Basel II/III, Solvency II and local initiatives like the Swiss Solvency Test [SST06], for an overview we refer to Sandstrm [Sa06, Sa07]). The financial crisis of 20072010 and the European sovereign debt crisis have also shown that there is still a long way to go (leading economists view these last financial crises as the worst ones since the Great Depression of the 1930s). These crises have (again) shown that risks need to be understood and managed properly on the one hand, and on the other hand that mathematical models, their assumptions and their limitations need to be well-understood in order to analyze and solve real world problems.

Concerning insurance companies: the goal of the solvency initiatives is to protect the policyholder and/or the (injured) third party, respectively, from the consequences of an insolvency of an insurance company. Henceforth, in most cases it is not primarily the objective of the regulator to avoid insolvencies of insurance companies, but given that an insolvency of an insurance company has occurred, the regulator has to ensure that all (insurance) liabilities are covered with assets and can be fulfilled in an appropriate way (this is not the shareholders point of view).

An early special project was carried out by the London working group. The London working group analyzed 21 cases of solvency problems (actual failures and near misses) in 17 European countries. Their findings can be found in the famous Sharma Report [Sha02]. The main lessons learned are:

in most cases bad management was the source of the problem;

there was a lack of a comprehensive risk landscape;

the company had misspecified business strategies which were not adapted to local situations.

From this perspective, what can we really do?

Sharma says: Capital is only the second strategy of defense in a company, the first is a good risk management.

Supervision has started several initiatives to strengthen the financial basis and to improve risk management thinking within the industry and companies (e.g. Basel II/III, Solvency II, Swiss Solvency Test [SST06], LaevenValencia [LV08], Besar et al. [BBCMP11]). Most of the new approaches and requirements are formulated in three pillars:

Pillar 1: Minimum financial requirements (quantitative requirements)

Pillar 2: Supervisory review process, adequate risk management (qualitative requirements)

Pillar 3: Market discipline and public transparency

Consequences are that regulators, academics as well as actuaries, mathematicians and risk managers of financial institutions are searching for appropriate solvency regulations. These regulations should be risk-adjusted and they should be based on a market-consistent valuation of the balance sheet (full balance sheet approach).

From this perspective we derive the valuation portfolio which reflects a market-consistent actuarial valuation of the balance sheet (which is more a static view). Moreover, we describe the uncertainties within that portfolio which corresponds to a risk-adjusted dynamic analysis of the assets and liabilities.

1.2 Solvency

The International Association of Insurance Supervisors IAIS [IAIS05] defines solvency as follows:

the ability of an insurer to meet its obligations (liabilities) under all contracts at any time. Due to the very nature of insurance business, it is impossible to guarantee solvency with certainty. In order to come to a practicable definition, it is necessary to make clear under which circumstances the appropriateness of the assets to cover claims is to be considered, ....

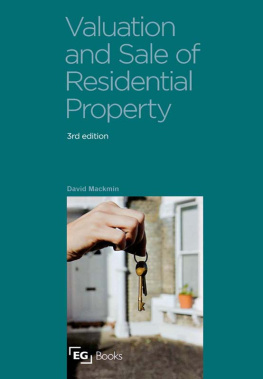

Fig. 1.1

Balance sheet of an insurance company with solvency relation ()

The aim of solvency is to protect the policyholder and/or the (injured) third party, respectively. As it is formulated in Swiss law: it is not the main objective of the regulator to avoid insolvencies of insurance companies, but in case of an insolvency the policyholders demands must still be met. Avoiding insolvencies must be the main task of the management and the board of an insurance company. Moreover, hopefully, modern risk-based solvency requirements ensure more stability of the financial system.

In this lecture we give a mathematical approach and interpretation to the solvency definition of the IAIS [IAIS05].

Let us start with two definitions (see also Fig. ):

Available Solvency Surplus (see [IAIS05]) or Risk Bearing Capital RBC (see [SST06]) is the difference between the market-consistent value of the assets minus the market-consistent value of the liabilities. This corresponds to the Available Risk Margin, the Available Risk Capacity or the Financial Strength of a company.

Required Solvency Margin (see [IAIS05]) or Target Capital TC (see [SST06]) is the required risk capacity (from a regulatory point of view) in order to be able to run the business such that certain adverse scenarios are also covered (see solvency definition of the IAIS [IAIS05]). This is the Necessary Risk Capacity, Required Risk Capacity or the Minimal Financial Requirement for writing well-specified business.

The general solvency requirement is then given by:

that is, the underlying risk (measured by TC) needs to be dominated by the available risk capacity (measured by RBC). Otherwise, if () is not satisfied, the authorities force the company to take certain actions to improve the financial strength or to reduce the risks within the company, such as: write less risky business, purchase protection (like derivative securities or reinsurance), sell part of the business or even close the company, and make sure that another company guarantees the smooth run-off of the liabilities.