THE

FIRST AMERICAN

COOKBOOK

A FACSIMILE

of American Cookery, 1796

by

Amelia Simmons

With an Essay

Mary Tolford Wilson

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright 1958 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

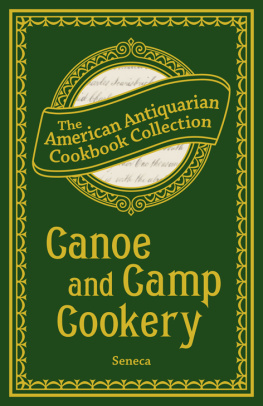

All rights reserved.

This Dover edition, first published in 1984, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of American Cookery , as published by Oxford University Press, New York, in 1958. The present edition is published with the permission of Oxford University Press, and of The William and Mary Quarterly: A Magazine of Early American History , in which the Wilson essay originally appeared (3d Ser., Vol. XIV, No. 1, January 1957; copyright 1957 by the Institute of Early American History and Culture). The perfect copy of the original edition of American Cookery used for the 1958 Oxford edition was reproduced by courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Simmons, Amelia.

The first American cookbook.

Reprint. Originally published: American cookery. New York: Oxford University Press, 1958.

1. Cookery, American Early works to 1800. I. Simmons, Amelia. American cookery. II. Title.

TX703.S53 1984 641.5973 84-4205

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-24710-6

ISBN-10: 0-486-24710-4

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

24710421

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS

__________

MARY TOLFORD WILSON

L ong after Stephen Day had begun the operation of a printing press in the infant Massachusetts Bay colony, the American who sought printed guidance in almost any branch of temporal affairs was still forced to rely upon European works. Those that walk mournfully with God might turn to Richard Standfasts Little Handful of Cordial Comforts for Fainting Souls , printed in Boston, or to any of the numerous sermons that flowed from colonial American presses; but the man who needed to know the best time to plant his wheat and the housewife whose receipt for syllabub was not completely to her taste could find help only in imported books.

For aid in such mundane matters, the English-speaking colonist might bring with him Thomas Tussers Five Hundreth Pointes of good Husbandrie , first printed in 1573 and frequently reissued. This work was doubly desirable because it also contained a section devoted to Huswiferie . The rhymed advice in Tussers appealing book covered every aspect of life on the land and in the house, from sowing peason and beans, in the wane of the moone, to marking new blankets and sheets. However, from the housewifes point of view, it was in many ways too general. For example, it contained no recipes for the pancakes, wafers, seed cakes, pasties, and frumenty that he recommended to her for use on such special occasions as Shrove Tuesday, sheepshearing, or harvest home.

Unless she was illiterate or unusually shiftless, the homemaker of course had her own written collection of receipts, medicinal as well as culinary, gathered from family and friends. A surprising number of early English manuscript receipt books, many of them beautifully written, have survived and can now be found in such collections as the Bitting in the Library of Congress and the Whitney in the New York Public Library.

After Gervase Markhams popular works began dispensing their widely inclusive advice, the seventeenth-century wife might find that her sporting husbands copy of Markhams Countrey Contentments included, in addition, The English Huswife: Containing the Inward and Outward Vertues which ought to be in a Compleate Woman .

Markhams English Huswife , besides containing a lengthy section devoted to cookery, which began with a calendar for planting necessary herbs in the right phases of the moon, also gave explicit advice about dairying and brewing; on making hempen, linen, and woolen cloth; and on how to achieve vertue in physick, which covered everything from remedies for griefes in stomacke and an ointment to breede haire to cures for consumption and the plague. As for the inward virtues the housewife ought to possess, these, too, covered a wide field. They ranged from being religious to being witty, from being chaste of thought to being wise in discourse but not frequent therein. Save that Markhams book lacked candlemaking instructions, the English housewife could scarcely have wished for a work better calculated to guide her in all her activities. The colonial wife, on the other hand, would come to feel that the work had certain lacunae. In America she had learned to use native-materials, the butternut in her dye pot, for example. But until a more specifically American work could be written, a book like Markhams was invaluable to her.

The success of Markhams publications encouraged many another author eager to advise on household affairs. The seventeenth century saw a marked increase in the number of such works printed in England. Cabinets and Closets, including Queen Henrietta Marias, were opened to disclose receipts for cookery, confectionery, distilling, physick, and chirgurie.

The next century produced an almost overwhelming number of English works embracing the art of cookery. Many were the product of women writers, and an increasing proportion dealt exclusively with cooking. The varieties offered were numerous: queens, royal, court, Englands new, modern, complete, professed, easy, and economical. The cooks whom the works were intended to suit were characterized by even more diverse adjectives: British, English, London, court, country, universal, modern, complete, family, pastry, experienced, prudent, frugal, and accomplished. A colonial bookseller thus had a wealth of titles from which he might choose to please his growing clientele.

But long as was the list from which she might select, the needs of the eighteenth-century American housewife could not be completely met by any one of the British works. Colonial cookery had undergone numerous changes since her ancestors had first established homes in the New World, and British authors seemed unaware of the resulting American needs in cooking instructions.

It was a noteworthy event, therefore, when the first edition of Amelia Simmonss American Cookery appeared in Hartford, Connecticut, in the spring of 1796. So far as we know this was the first cookbook of American authorship to be published in the United States. The work was an unpretentious volume, paper covered, and of only forty-seven octavo pages. Its contents lived up to its straightforward title: the receipts it contained and its section on Catering, or the Procuring the Best Viands, Fish, &c recorded the changes that had taken place in our cookery and even in our speech. Moreover, the inclusion of many of these American variations marked their first appearance in print. Consequently, Amelia Simmonss work was, in its minor sphere, another declaration of American independence.

Credit should in fairness be given to an earlier attempt to publish a cookbook particularly suited to American users. William Parks, printer at Williamsburg, was the innovator. When he published his edition of E. Smiths Compleat Housewife in 1742, he did so with the stated purpose of excluding receipts, The Ingredients or Materials for which, are not to be had in this Country. Such things as skirrets and broom buds apparently fell within that category. In so far as he followed his guiding principle of including only such receipts as were useful and practicable here, the cookery section of Parkss book might also be labeled American. But this negative approach could not mirror, as Amelia Simmonss book did, the changes that Americans had been making in their cookery.

Next page