A LSO BY S TEPHEN H AWKING

A Brief History of Time

A Briefer History of Time

Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays

The Illustrated A Brief History of Time

The Universe in a Nutshell

FOR CHILDREN

Georges Secret Key to the Universe (with Lucy Hawking)

Georges Cosmic Treasure Hunt (with Lucy Hawking)

A LSO BY L EONARD M LODINOW

A Briefer History of Time

The Drunkards Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives

Euclids Window: The Story of Geometry from Parallel Lines to Hyperspace

Feynmans Rainbow: A Search for Beauty in Physics and in Life

FOR CHILDREN

The Last Dinosaur (with Matt Costello)

Titanic Cat (with Matt Costello)

Copyright 2010 by Stephen W. Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow

Original art copyright 2010 by Peter Bollinger

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Cartoons by Sidney Harris, copyright Sciencecartoonsplus.com

B ANTAM B OOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-553-90707-0

www.bantamdell.com

v3.0_r1

E EACH EXIST FOR BUT A SHORT TIME, and in that time explore but a small part of the whole universe. But humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time.

E EACH EXIST FOR BUT A SHORT TIME, and in that time explore but a small part of the whole universe. But humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time.

Traditionally these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge. The purpose of this book is to give the answers that are suggested by recent discoveries and theoretical advances. They lead us to a new picture of the universe and our place in it that is very different from the traditional one, and different even from the picture we might have painted just a decade or two ago. Still, the first sketches of the new concept can be traced back almost a century.

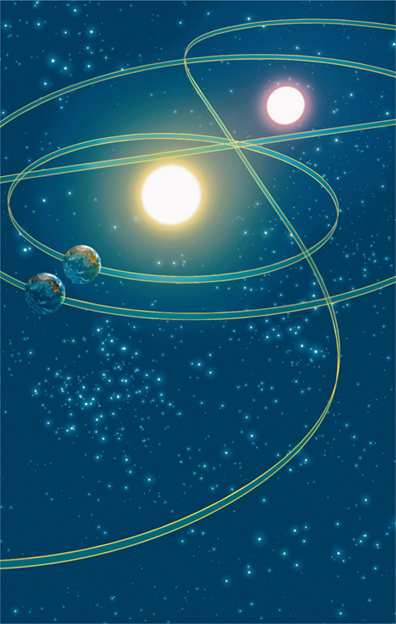

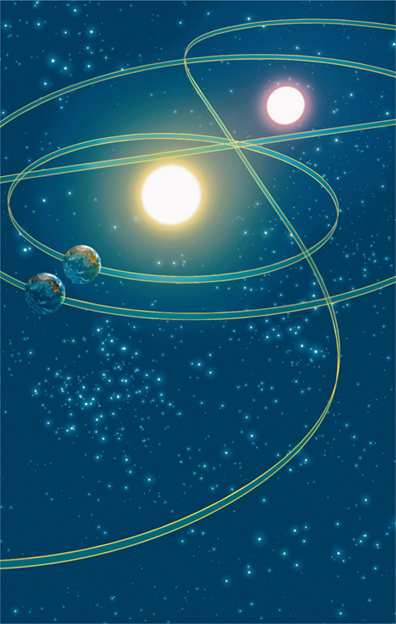

According to the traditional conception of the universe, objects move on well-defined paths and have definite histories. We can specify their precise position at each moment in time. Although that account is successful enough for everyday purposes, it was found in the 1920s that this classical picture could not account for the seemingly bizarre behavior observed on the atomic and subatomic scales of existence. Instead it was necessary to adopt a different framework, called quantum physics. Quantum theories have turned out to be remarkably accurate at predicting events on those scales, while also reproducing the predictions of the old classical theories when applied to the macroscopic world of daily life. But quantum and classical physics are based on very different conceptions of physical reality.

Quantum theories can be formulated in many different ways, but what is probably the most intuitive description was given by Richard (Dick) Feynman, a colorful character who worked at the California Institute of Technology and played the bongo drums at a strip joint down the road. According to Feynman, a system has not just one history but every possible history. As we seek our answers, we will explain Feynmans approach in detail, and employ it to explore the idea that the universe itself has no single history, nor even an independent existence. That seems like a radical idea, even to many physicists. Indeed, like many notions in todays science, it appears to violate common sense. But common sense is based upon everyday experience, not upon the universe as it is revealed through the marvels of technologies such as those that allow us to gaze deep into the atom or back to the early universe.

Until the advent of modern physics it was generally thought that all knowledge of the world could be obtained through direct observation, that things are what they seem, as perceived through our senses. But the spectacular success of modern physics, which is based upon concepts such as Feynmans that clash with everyday experience, has shown that that is not the case. The naive view of reality therefore is not compatible with modern physics. To deal with such paradoxes we shall adopt an approach that we call model-dependent realism. It is based on the idea that our brains interpret the input from our sensory organs by making a model of the world. When such a model is successful at explaining events, we tend to attribute to it, and to the elements and concepts that constitute it, the quality of reality or absolute truth. But there may be different ways in which one could model the same physical situation, with each employing different fundamental elements and concepts. If two such physical theories or models accurately predict the same events, one cannot be said to be more real than the other; rather, we are free to use whichever model is most convenient.

In the history of science we have discovered a sequence of better and better theories or models, from Plato to the classical theory of Newton to modern quantum theories. It is natural to ask: Will this sequence eventually reach an end point, an ultimate theory of the universe, that will include all forces and predict every observation we can make, or will we continue forever finding better theories, but never one that cannot be improved upon? We do not yet have a definitive answer to this question, but we now have a candidate for the ultimate theory of everything, if indeed one exists, called M-theory. M-theory is the only model that has all the properties we think the final theory ought to have, and it is the theory upon which much of our later discussion is based.

M-theory is not a theory in the usual sense. It is a whole family of different theories, each of which is a good description of observations only in some range of physical situations. It is a bit like a map. As is well known, one cannot show the whole of the earths surface on a single map. The usual Mercator projection used for maps of the world makes areas appear larger and larger in the far north and south and doesnt cover the North and South Poles. To faithfully map the entire earth, one has to use a collection of maps, each of which covers a limited region. The maps overlap each other, and where they do, they show the same landscape. M-theory is similar. The different theories in the M-theory family may look very different, but they can all be regarded as aspects of the same underlying theory. They are versions of the theory that are applicable only in limited rangesfor example, when certain quantities such as energy are small. Like the overlapping maps in a Mercator projection, where the ranges of different versions overlap, they predict the same phenomena. But just as there is no flat map that is a good representation of the earths entire surface, there is no single theory that is a good representation of observations in all situations.

Next page

E EACH EXIST FOR BUT A SHORT TIME, and in that time explore but a small part of the whole universe. But humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time.

E EACH EXIST FOR BUT A SHORT TIME, and in that time explore but a small part of the whole universe. But humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time.