To the two gentlest souls I know:

my late dog Mattiebo, who introduced me to the wonders of our yard that my duller human senses could not have perceived on their own,

and my husband, Will Heinz, who treats all living creatureshuman, animal, and plant with the kindness and dignity they deserve.

Published by Princeton Architectural Press

A McEvoy Group company

37 East 7th Street, New York, New York 10003

202 Warren Street, Hudson, New York 12534

www.papress.com

2017 Nancy Lawson. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Sara Stemen Designer: Benjamin English

Developmental editor: Simone Kaplan-Senchak

Special thanks to: Janet Behning, Nicola Brower, Abby Bussel, Erin Cain, Tom Cho, Barbara Darko, Jenny Florence, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Lia Hunt, Mia Johnson, Valerie Kamen, Diane Levinson, Jennifer Lippert, Kristy Maier, Sara McKay, Eliana Miller, Jaime Nelson Noven, Esme Savage, Rob Shaeffer, Paul Wagner, and Joseph Weston of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

NAMES : Lawson, Nancy, 1970 author.

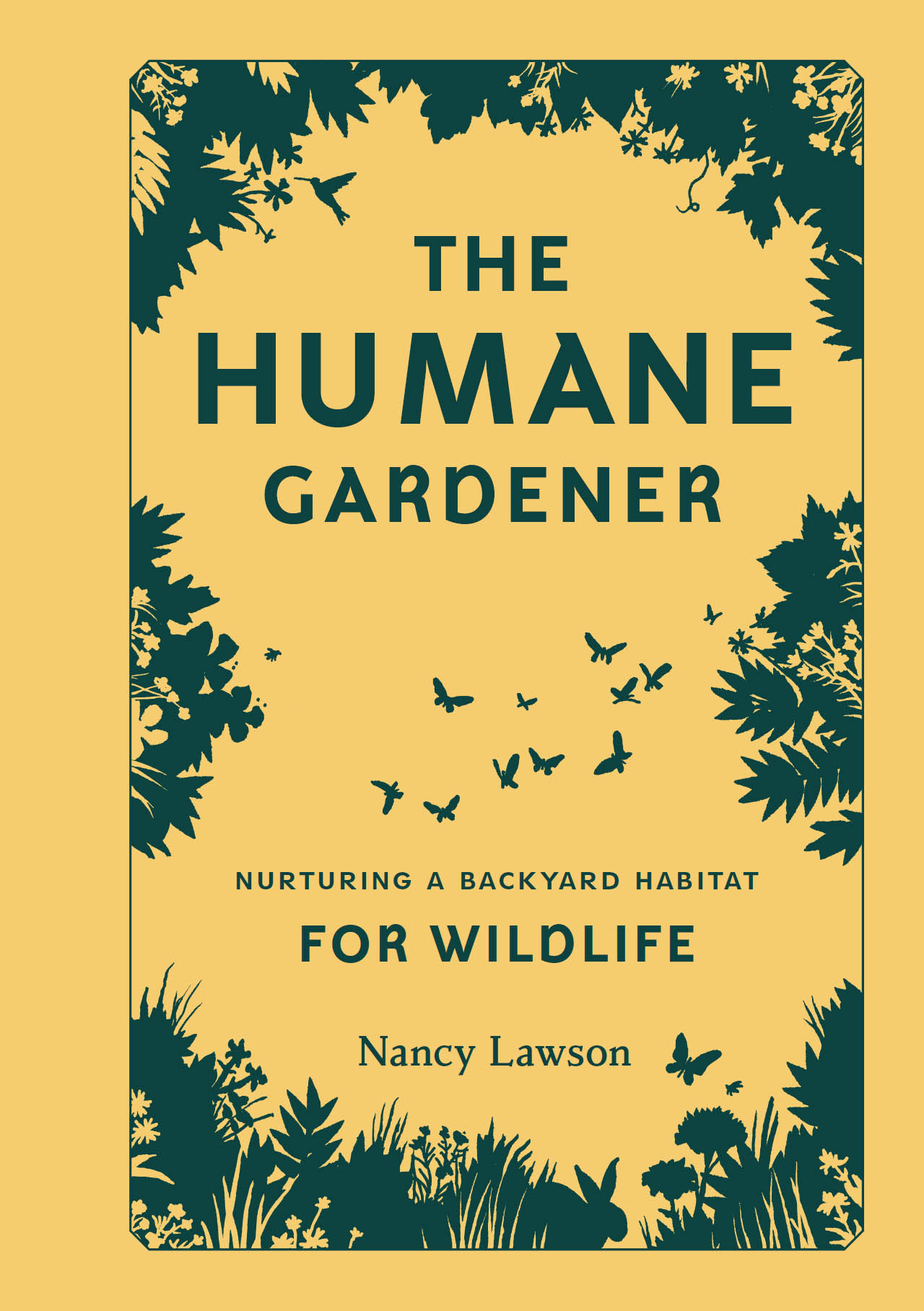

TITLE : The humane gardener : nurturing a backyard habitat for wildlife / Nancy Lawson.

OTHER TITLES : Nurturing a backyard habitat for wildlife

DESCRIPTION : First edition. | New York : Princeton Architectural Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references.

IDENTIFIERS : LCCN 2016029007 | ISBN 9781616895549 (alk. paper) ISBN 9781616896171 (epub, mobi)

SUBJECTS : LCSH: Gardening to attract wildlife. | Garden ecology.

CLASSIFICATION : LCC QL59 .L395 2017 | DDC 577.5/54dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016029007

AUTHORS NOTE

Though conventional style guides have long frowned upon the practice, I use gender pronouns when referencing animalsfrom coyotes to caterpillarsthroughout this book. After working for many years as an editor at the Humane Society of the United States, I became so accustomed to it that I wouldnt think of going back. Animals are not inanimate objects, and neither are any of the other living creatures among us, yet we use language to separate ourselves from nonhuman beings. As Robin Wall Kimmerer notes in Braiding Sweetgrass,

Maybe a grammar of animacy could lead us to whole new ways of living in the world, other species a sovereign people, a world with a democracy of species, not a tyranny of onewith moral responsibility to water and wolves, and with a legal system that recognizes the standing of other species. Its all in the pronouns.

INTRODUCTION

I used to make many paths into the garden, but somehow nature always found a way to color outside the lines, foiling my straight-and-narrow routes with unruly stalks and new shoots. I would yank her additions out, relocate them, and whine to myself about such encroachments on my prefabricated vision of what a yard should be.

It would be years before I understood that while paths through our two-acre plot were arbitrary for us human inhabitants, they were a much-needed escape for other speciesthe one place where a plant could at least seed, sprout, take hold, and perhaps be noticed instead of mowed down. Early in my gardening journey, these flamboyant wildflowers would have been better off as wallflowers. Unfortunately for the plants and animals who depended on them, each new sign of life was guilty until proven innocent, a threat to the establishment.

One such interloper came in the form of a broad-leaved and thick-stemmed suspect I noticed on my way to work one morning. Daring to inch up in front of our split-rail fence, it looked ominously ready to overtake our property if I didnt act fast. There was no hesitation as I walked past my husband with his power trimmer and issued the death sentence: Off with his head!

Less than twenty minutes passed before a roadside sighting of the same species in bloom alerted me to my error and prompted a phoned-in stay of execution. But it was too late. I had casually ordered the ritual decapitation of a plant that, had I only let it, would soon have hosted hundreds of animals: the beautiful but unfortunately named common milkweed.

In retrospect, its not surprising that my most influential learning experience in horticulture came while sitting at a traffic light next to a neglected ditch at the intersection of a major highway and a nondescript suburban road. Those are the areas where the pretty plants grow and the hungry creatures go. Often listed as preferred habitats of wildflowers, these so-called waste places are forgotten spaces, spared temporarily from human interference while we go about our business of tearing nature down elsewhere. They are some of the last areas on our large patch of the planet for our fellow species to colonize and survive.

All my years of consuming mainstream gardening publications and TV shows hadnt prepared me for my milkweed sighting, nor had my Master Gardener training. In fact, even at a time when gardeners around the country are clamoring to plant milkweed species to save the monarch butterfly, who can lay her eggs on nothing else, Marylands Master Gardener manual still lists this plant as a problematic invader.

By these conventional standards, my property is a disaster. Its now filled with members of wildlife-sustaining species that have been cut down, dug up, sprayed, and otherwise brutalized on this continent for decades, sometimes centuries. Its home to any animal who wants to make a life here and refuge to others just passing through. Only two things are unwelcome: chemicals and invasive vegetation known to supplant wildlife habitat. Everyone else, from smartweed to milkweed, from ground beetles to groundhogs, has an open invitation.

The guest list, of course, wasnt always so inclusive. Before my milkweed revelation, I was an unwittingly graceless host to many other species, once aiming a hose at a mass of ladybug eggs, thinking they were aphids. I ripped out jewelweed, a hummingbird favorite, assuming from its name that it was a trespasser with nefarious intentions. I cut down walnut and hickory saplings, mistaking them for the invasive tree of heaven.

My heart was mostly in the right place, but my head was steeped in the marketing ploys of the Landscaping Industrial Complex, not to mention long-ingrained cultural sentiments that divide the world into endless false dichotomies: beneficial insects versus pests, acceptable garden plants versus weeds, order versus chaos. Feeding a multibillion-dollar industry hawking all manner of poisonous potions and outsized tools is a constant stream of cynical advertisements that prey on our insecurities and cater to our basest fears. From their warlike parlance, we learn that animals are out to get us, that plants are messy, that humans reluctant to unleash weapons of mass destruction on denizens of the natural worldespecially insectsare freaks of nature themselves.

The attempt to engender fear of other species stretches well beyond negative portrayals of invertebrates. Chemical giants advise destroying all insects in the ground because if you dont, God forbid, youll see animals such as skunks and birds visiting your lawn to feed

Next page