Table of Contents

ALSO BY EUGENE LINDEN

The Winds of Change

The Octopus and the Orangutan

The Parrots Lament

The Future in Plain Sight

Silent Partners

Affluence and Discontent

The Alms Race

Apes, Men, and Language

For my children,

their children yet to be born

and all those on whom it will fall

to restore this tattered planet

Introduction

I never boarded an airplane before college, but just a year after graduation I began a series of forays to some of the most remote, wild and calamitous parts of the globe. First I went to Vietnam as a journalist, making a round-the-world trip out of the getting there and getting back. Then it was off to Africa and New Guinea during the writing of my early books, and then virtually everywhere else as a journalist reporting on global environmental issues for Time, and on assignment for National Geographic and other magazines.

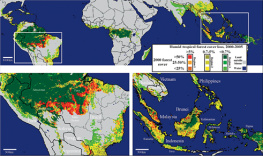

These travels were prompted by diverse writing assignments, but all were informed by a hunger to see what I call the ragged edge of the world, the places where wildlands, indigenous cultures and modernity collide. Since my childhood, when I watched rustic neighborhoods give way to strip malls and tract homes, Ive been acutely sensitive to change and loss. Those feelings intensified as I traveled to places such as Polynesia, Borneo, the Amazon and the Arctic. Time and again I saw traditional cultures encounter and succumb to the power of modern money, technology, ideas and images. Even places with no humans whatsoever feel the force of our presence. In the Ndoki, a remote and magical rainforest in the Congo where not even the Pygmies have ventured during the past thousand years, the impact of humanity intrudes in the dust that blows in from the desertified Sahel in the north, and in an ominous drying-out of the forest due to logging in the surrounding areas.

Nostalgia is the word we use to describe the bittersweet evocation of precious feelings that lie just beyond reach in the past. Often the emotion arises during rites of passage or out of the intricate matrix of personal history, memory and place, but what word or phrase adequately describes the feelings evoked by repeatedly observing the disappearance of an entire landscape, a people, a language, or a way of life? It is akin to forever showing up for the last scenes of a tragedy in which one can glimpse, but never fully experience, the past glory of the protagonist.

In the course of my career, I became a monitor of the march of modernity. Like some modern Josephus, in my forty years of travels I have witnessed the battles at the front lines of change, followed the retreat of the world where magic still lives and where animals and spirits dominate. And I have documented the human and animal detritus left behind in the aftermath of the advancing armies of the consumer society.

Today, many of the locales of my early travels bear little resemblance to the places I first visited. Even the most remote areas have become more accessible. Three years before I explored the Ndoki Forest, it took five days to negotiate the quicksand and swamps that guard the perimeter of this enchanted place. By 1991, when I traveled there, scientists had laid down some logs as a primitive path through part of the swamp, and it took us a day and a half to get from the tiny village of Bomassa to the edge of the river and swamps that isolate the Ndoki from the rest of the Congo. Now a car can take visitors to the banks of the Ndoki River in half an hour. Mike Fay, the explorer who brought me into the Ndoki, says that the first alarms about threats to the region were met with skepticism because a huge buffer of uncut forest surrounded it. Now every forest surrounding the Ndoki has been logged.

The Ndoki persists inviolate, however, while other places and peoples I visited havent been so lucky. I traveled to the interior of Borneo in the early 1990s to write about the disappearing way of life of the Penans, a tribe of the last few hunter-gatherers remaining on that vast island. I witnessed firsthand a type of cultural Alzheimers as Penans just a few years and a few miles from their ancestral forests were quickly shedding knowledge acquired over millennia. Schoolkids in Marudi could recall that their uncles would hunt boar after the appearance of a particular butterfly, but they could not recall which butterfly it was or when it appeared. Now only a handful of Penans preserve that culture in Borneos fast-disappearing forests.

When I visited Chico Mendezs home in Acre, Brazil, in the late 1980s, Xapuri was a sleepy one-horse river town separated from the rest of the state by unbroken rainforest. Now the town has supermarkets and a highway connecting it to Rio Branco, the state capital. Some rubber tappers remain, but Xapuri now also has factories, and kids with bookbags walk along its suburban roads.

Some cultures have shown remarkable resilience in maintaining their identity while trying to reap some of the benefits of material advances. In Polynesia many of the outward trappings of the old ways have disappeared, but some islands retain a distinctly Polynesian spirit in their way of life.

Moreover, if that ragged frontier is retreating in much of the world, it is advancing in others. In some parts of Central Africa, modernity and its attendant infrastructure are disappearing, and traditional ways are recolonizing peoples just as a strangler fig will gradually displace its host tree. Sometimes when the modern economy flounders, a toxic brew of banditry, superstition and cultural anarchy takes its place. In other regions, indigenous cultures reclaim modern myths and stories. At a Christian mission on an island in New Guinea, the presiding native priest (the European missionaries had long since departed) narrated to me a history of the island that seamlessly melded Christian and animist myths.

Even on our crowded planet there remain lost worlds, places that seem to have escaped the intrusions of the consumer economy and persist in a time warp. From an animals point of view, the Ndoki in the Congo is one such place, as are parts of Antarctica, and Vu Quang in the cordillera that separates Vietnam and Laos.

When writing about these and many other places, I almost always had some journalistic purpose that relegated the enchanting encounters and revelatory vignettes of my travels to the background. If I went to the Ndoki, it was because humans were encroaching and I wanted to raise the alarm. If I went to the Antarctic, it was to try to understand what role this vast and frigid continent might play in the worlds rapidly changing climate. If I went to Borneo, it was to talk with Penan chiefs about the disappearance of their culture, or to report on the plight of the forest and its creatures.

To be sure, Id take pains to try to evoke the flavor and wonder of these locales. It is hard, however, when writing for National Geographic about pygmy chimps, to venture into a digression about an encounter with a brutal, thieving commandante in the heart of Equateur. When reporting on cargo cults in the highlands of New Guinea and what they might suggest about the nature of consumer societies, it would be disruptive to veer off into an account of a trip with the police to arrest a grass-skirted rapist that included a pleasant stop on the way back to town during which the cop, the rapist and I toured a bird of paradise sanctuary.