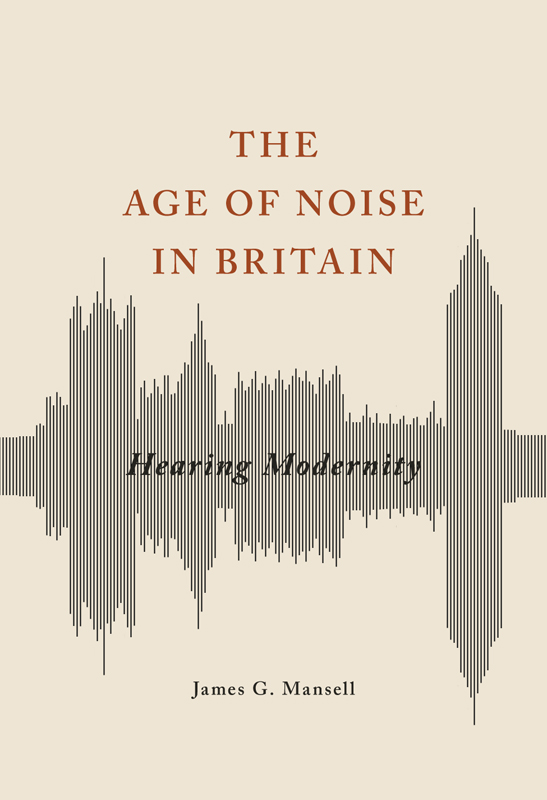

The Age of Noise in Britain

STUDIES IN SENSORY HISTORY

Series Editor

Mark M. Smith, University of South Carolina

Series Editorial Board

Martin A. Berger, University of California at Santa Cruz

Constance Classen, Concordia University

William A. Cohen, University of Maryland

Gabriella M. Petrick, New York University

Richard Cullen Rath, University of Hawaii at Mnoa

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

The Age of Noise

in Britain

Hearing Modernity

JAMES G. MANSELL

University of Illinois Press

URBANA, CHICAGO, AND SPRINGFIELD

2017 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on the

Library of Congress website.

Contents

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my doctoral supervisors, particularly Bertrand Taithe, for their guidance and support, as well as those who broadened my outlook as a postdoctoral researcher, especially Maiken Umbach, whose mentorship was invaluable, and Scott Anthony, with whom I had great fun collaborating on the history of the GPO Film Unit. I am grateful to the University of Nottingham for affording me the time to write the book and to my colleagues in the Department of Culture, Film, and Media for their encouragement and friendship, especially Tracey Potts. My students on the module Hearing Cultures are also a constant source of inspiration. I might not have had the confidence to include done any of it without the support of my friends and family. Writing this book has absorbed my energy for a long time, and Im so grateful that when Ive come up for air there have still been people around to talk to. The book is dedicated to my parentsJulia and Gilbertwhose quiet support was what I needed, and to Lucie, who has lived through every detail of it with me, and whose ideas and love are manifested on every page.

The Age of Noise in Britain

Introduction

When the complete history of the present period comes to be written, it should surely be described as the age of noise.

W. S. Tucker, The Age of Noise, a lecture to the Royal Aeronautical Society, quoted in the Manchester Guardian (January 20, 1928)

That historians should have left Tuckers prophecy unfulfilled is hardly surprising. Noise was not just representative of the modern; it was modernity manifested in audible form. Discussing noise allowed commentators to express what it felt like to be living in modern times. Noise was clamorous, all-enveloping, and unpredictable. Discussions of the age of noise constituted a conscious engagement with the politics of modernity in which the modern was not primarily a set of ideas, institutions, or practices, but rather the sensed experience of an unnerving atmosphere.

The age-of-noise narrative circulated widely in early-twentieth-century Britain, as it did in other industrialized nations. Newspaper letter pages filled Thanks to a whole host of new technologiesmotor vehicles, airplanes, typewriters, gramophone loudspeakers, wireless sets, telephones, vacuum cleaners, evennoise was said to have penetrated every facet of daily life. Thanks also to the ongoing and ever-denser concentration of people in towns and cities, auditory respite was said to be increasingly difficult to find. Noises rhythms and vibrations caught hold of the hearers day and night, refusing them let-up from the flux and pace of twentieth-century life. Noise imposed a modern state of being on its hearers, whether they liked it or not.

British newspapers reported on the major developments of the day from the perspective of the age of noise. To offer an instructive example, the practice of remembering the dead of the Great War with two minutes of silence on Armistice Day was greeted as recognition of the wars place in the age of noise:

When everyone was wondering what would be the most striking way in which to commemorate the end of the war with all its tremendous burden of sorrowful memory, someone had an idea which the country at once seized on as an inspiration of genius. We should be quiet for two minutes! All our trams and buses, motor-cars, lorries and carts, all our gongs and bells and buzzers, our banging and hammering and thumping, even our chattering and shouting, should be hushed. The idea was that the magnitude of the moment should be emphasized by something as remote as the mind could conceive from our normal lives, and the universal enthusiasm with which we seized on the significance of silence provedif proof were wantingthat everyone recognized Noise as the outstanding characteristic of our age.

Not satisfied with two minutes of silence, the Times reported in 1927 that Londoners would be invited to participate with finger on the lip, in a full week of silence, during which participants should speak low and walk with soft and ginger tread.

Newspapers also reported on all manner of supposed cures for noise sensitivity. During the blitz of 1940, American scientists were reported to have proven that vitamin B1 could protect against nervous susceptibility to bomb noise. The Manchester Guardian ran a competition for the best response to this news. First prize went to Miss K. M. Fell of Swinton for a rhyme that encapsulates the simultaneous gravity and dark frivolity with which the noise question was treated in early-twentieth-century Britain:

Two doctors from the burgh of Pitts,

Seeking to counteract the Blitz

(For noise, they think, results in fits).

Declare that now we may cry Quits

Gainst wars of nerves devised by Fritz.

And so, when dining at the Ritz,

Mid roar of bombs and Messerschmitts,

The dauntless Briton calmly sits

Munching B 1, the cream of Vits.

Historians have pointed to the centrality of nervousness as a mode of narrating the early-twentieth-century experience of modernity. Over years, this kind of strain would lead, it was feared, to a waning of bodily vitality and ultimately, in some cases, to complete nervous breakdown. The Naziss noisy aerial bombardment of British towns and cities during the Second World War was supposed, at the time, to be a deliberate attempt to accelerate this process.

Anxieties about noise, it should be noted, are far from unique to the early twentieth century. Through the nineteenth century, and before that, people complained about street sounds.

In Britain, the age-of-noise narrative was also the product of a no less historically specific anxiety about the progress of modernity at this time. The terrible sacrifices of the First World War prompted an acute crisis of faith in Noise thus encapsulated a paradox at the heart of early-twentieth-century modernity: the more it advanced, the more intolerable life would become. Hopes and fears for noise, such as Huxleys, were expressive, ultimately, of hopes and fears for the sensing human subject in an age of machines.

Taking the hopes and fears of Britains age of noise as its starting point and case study, this book asks how we might come to reinterpret early-twentieth-century modernity by paying attention to its cultures of hearing. By rereading the available source material in search of insight into the heard experience, we may come to better understand how modern subjectivities were constituted, the book suggests. Subject formation depends upon external sensory referents. What people hear in their daily lives has a role to play in how they imagine themselves. It plays a part in connecting selves to others through, for example, the unifying cheers of a crowd or, conversely, the unwelcome sound of a neighbors barking dog. It also plays a role in how people experience connection to place: to the quiet privacy of home, for instance; to the noisy rhythms of the workplace or to the sonic properties of specific locales. How one hears is also a marker of who one is. Hearing is not a passive experience; nor is it free from ideology. Choices about what to hear and how to hear it are part of the historical processes of self and social formation. Those who seek to wield authority and influence understand this only too well, even if historians and other analysts of power have been slow to catch up. To understand these processes in any given context requires historicization. How a society makes meaning out of its sounds is fundamental to how it constructs belonging, exclusion, order, disorder, and discipline. This book argues that, in early-twentieth-century Britain, hearing played a more than usually important role in these imaginative constructions, particularly in relation to the urgent, and contested, task of reimagining modernity. The age-of-noise narrative thrust hearing to center stage in the quest to define and reshape modern ways of being. Those who could convincingly make normative claims in relation to the modernity of sound and hearingto define what constituted good and bad sounds and healthy or unhealthy ways of hearingcould in turn gain considerable authority as arbiters of both aurality and modernity.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.