MARIA MIES is a German feminist and activist scholar who lives in Cologne. She is the author of numerous groundbreaking works on women and globalisation. She has worked at the Goethe Institute in India, conducted fieldwork in Andhra Pradesh and was the founding director of the Masters in Women and Development at the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague in the Netherlands. She is Professor Emerita at the University of Applied Sciences (Fachhochschule) in Cologne.

She has always combined activism and scholarship and was central to establishing the first shelter for battered women in Cologne. Maria Mies has been involved in resistance to genetic engineering and reproductive technologies, the fight against the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI), against the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and on issues of food security, all fundamental components of corporate globalisation. She is known around the world for the concept of housewifisation and her writings on ecofeminism.

Other books by Maria Mies:

Indian Women and Patriarchy. Concept Publishers (1980)

Feminism in Europe: Liberal and Socialist Strategies 17891919 (1981)

National Liberation and Womens Liberation (1982, Rhoda Reddock)

Fighting on Two Fronts: Womens Struggles and Research (1982)

Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour (1986/1999)

Women: The Last Colony (1988, with Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen and Claudia von Werlhof )

Ecofeminism (1993, with Vandana Shiva)

The SubsistencePerspective: Beyond the Globalised Economy (1999, with Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen)

The Village and the World: My Life, Our Times (2010)

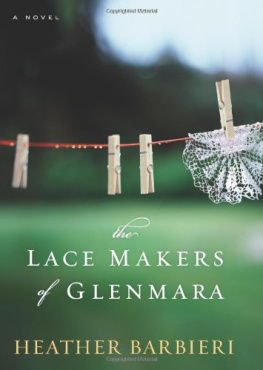

The Lace Makers

of Narsapur

Indian Housewives Produce for the

World Market

Maria Mies

First published by Zed Books, London, 1982

First published by Spinifex Press, Australia 20102

Spinifex Press Pty Ltd

504 Queensberry St

North Melbourne, Victoria 3051

Australia

women@spinifexpress.com.au

www.spinifexpress.com.au

Maria Mies, 1982, on new Preface, 2012

on layout Spinifex Press, 2012

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Copying for educational purposes

Information in this book may be reproduced in whole or part for study or training purposes, subject to acknowledgement of the source and providing no commercial usage or sale of material occurs. Where copies of part or whole of the book are made under part VB of the Copyright Act, the law requires that prescribed procedures be followed. For information contact the Copyright Agency Limited.

Cover design by Deb Snibson, MAPG

Printed by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Mies, Maria.

The lace makers of Narsapur / Maria Mies.

9781742198149 (pbk.)

9781742198088 (ebook : pdf )

9781742198125 (ebook: epub)

9781742198095 (ebook : Kindle)

Spinifex feminist classic.

Includes bibliographical references.

Women lace makersIndiaNarsapur.

Lace and lace makingIndiaNarsapur.

Sexual division of laborIndiaNarsapur.

305.4677

Preface to the 2012 edition

IAM very happy that Spinifex Press is publishing this reprint of The Lace Makers of Narsapur. Because most of what I learned about the exploitation of women by capitalism, patriarchy and colonialism I learned through my empirical fieldwork in Narsapur, a small town in South India. This research project provided the background for my further practical and theoretical understanding of how women as housewives through their invisible work contribute to the process of Capital Accumulation (see Mies, 1986/1999).

I started this study in 1979. This was the time when feminists all over the world were engaged in a heated debate on the question: Why is housework not considered work? Why is this work not paid? Why are only men called the breadwinners? Why dont women get a wage for their work? Why is the making of a car called productive, while a womans work for her family, her husband, her children is only reproductive work, as Marx had called it? In this context, we asked why does capitalism need this non-work for its process of unlimited growth of money?

To change this situation, some feminists demanded a wage for housework. Others, like myself, were of the opinion that men should share this non-waged work equally with women. That means they would have to do all the nitty-gritty jobs in the home which they usually do not even notice. They would have to spend much more time at home and much less time in the factory or in the office. The whole sexual division of labour would have to be changed and the labour power to produce ever more commodities for the capitalist market would shrink. Under such equal work conditions for men and women, capitalism could not have developed in the way it did.

My view was not shared by most feminists. But the discussion on housework under capitalist conditions went on for many years. Mostly, it was limited to a purely Western, Eurocentric perspective. Practically no one asked what this discussion meant for women in the poor countries of the global South.

Therefore my two friends, Claudia von Werlhof and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen and I asked whether this whole discussion about housework would make any sense for poor women in Africa, Asia and Latin America? Didnt they have other, more important problems to solve? All three of us had lived and worked in the socalled third world, Claudia and Veronika in Latin America and myself in India.

At the same time a similar discussion took place among young researchers who had studied the work conditions in developing countries on the mode of production. They had found that the majority of poor people working there were not proletarians in the classical sense of the word. They were working for their own survival as small peasants, small artisans, small shopkeepers, ragpickers, housemaids, rikshaw-pullers, tailors and in all kinds of similar casual jobs. The UN had called this whole sector the unorganised sector. We and others were not satisfied with this term and so we began calling this work Subsistence Work. Because all these people did not get a regular income, they had no job security, they had no insurance when they were sick or became old. Often they did not even have a proper place to live. In the cities, many of them lived in slums. The labour unions were not interested in these non-proletarians. But these people worked: they worked for their subsistence.