When I say the word bitch, what comes to mind? Let me guess: that girl you went to high school withthe one with the small nose who wore Britney Spears perfume and never invited you to her house parties. No? Then perhaps the word bitch conjures images of an old boss, or a roommate, or some famous she-villain like Cruella de Vil, that unholy puppy-murdering shmuck. Maybe the word bitch instantly catapults Kellyanne Conways face to your mind, like a jack-in-the-box straight from hell. Or maybe, if youre a literal sort, it makes you think of a female dog. No matter your species, there are just so many ways for a gal to be a bitch.

But what if I told you that eight hundred years ago, the word bitch had nothing to do with women (or canines, for that matter)? What if I told you that before modern English existed, an early version of the word bitch was actually just another word for genitaliaanyones genitaliaand that only after a long and colorful evolution did it come to describe a female beast, naturally leading to its current meaning: a bossy, evil, no-fun lady. What if I told you that this process of a totally neutral or even positive word devolving into some insult for women happens in the English language all the time? What if I told you that swimming under the surface of almost every word we say, there is a rich, glamorous, sometimes violent history infinitely more dramatic than any Disney movie or CNN debate? What if I told you that without even realizing it, language is impacting all of our lives in an astonishing, filthy, and fascinating way?

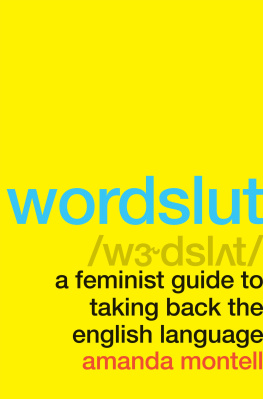

Cozy up, dear reader. Because this is a book about the psychedelic universe that exists behind the English language. Words are something so many of us take for granted, which of course makes perfect sense. We start learning language straight out of the womb (truly, at six weeks old were already experimenting with vowel sounds), and from then on, we come to wield it so naturally that we never really consider why it works the way it does. Growing up, I had no idea that there was a whole academic field dedicated to examining every infinitesimal detail of how language operates, from what your tongue is doing when you make an r sound to why Americans love British accents so much.

But every part of our speechour words, our intonation, our sentence structuresis sending invisible signals telling other people who we are. How to treat us. In the wrong hands, speech can be used as a weapon. But in the right ones, it can change the world. That may sound melodramatic, though I promise it isnt. Take it from a language scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara named Lal Zimman, who told me that one of our cultures biggest obstacles is the idea that language doesnt matter the way that other, more tangible forms of freedom and oppression do. Its that old mythology that sticks and stones may break your bones but words can never hurt you. Getting people to understand that language itself is a means through which people can be harmed, elevated, or valued is really important, Zimman says.

Zimman, like most of the other word whizzes I talked to for this book, is a linguist, a profession that (despite common misconceptions) has nothing to do with learning to speak dozens of foreign languages or correcting peoples split infinitives. Linguistics is, in fact, the scientific study of how language works in the real world. Under that umbrella falls sociolinguistics, where the studies of language and human sociology intersect. It actually wasnt that long ago (around the 1970s) when linguists first began studying how human beings use language as a social tool to do things like create solidarity, form relationships, and assert authority. Out of everything they investigated, the most eye-opening and contentious subject has undoubtedly been language and genderthat is, how people use language to express gender, how gender impacts how a person talks, and how their speech is perceived. Over the decades linguists have learned that pretty much every corner of language is touched by gender, from the most microscopic units of sound to the broadest categories of conversation. And because gender is directly linked to power in so many cultures, necessarily, so is language. Its just that most of us cant see it.

Speaking of power, you may or may not have heard of a little thing called patriarchy: a societal structure in which men are the central figures. Human societies havent always been patriarchalscholars believe mans rule began somewhere around 4000 BCE. (Homo sapiens have been around for two hundred thousand years in all, for context.) When people talk about smashing the patriarchy, theyre talking about challenging this oppressive system, linguistically and otherwise. Which is relevant to us because in Western culture, patriarchy has overstayed its welcome.

Its high time the subject of gender and words makes its way beyond academia and into the rest of our everyday conversations. Because twenty-first-century America finds itself in a unique and turbulent place for language. Every day, people are becoming freer than ever to express gender identities and sexualities of all stripes, and simultaneously, the language we use to describe ourselves evolves. This is interesting and important, but for some, it can be hard to keep up, which can make an otherwise well-meaning person confused and defensive.

Were also living in a time when we find respected media outlets and public figures circulating criticisms of womens voiceslike that they speak with too much vocal fry, overuse the words like and literally, and apologize in excess. They brand judgments like these as pseudofeminist advice aimed at helping women talk with more authority so that they can be taken more seriously. What they dont seem to realize is that theyre actually keeping women in a state of self-questioningkeeping them quietfor no objectively logical reason other than that they dont sound like middle-aged white men.

More troubling still, there are also plenty of folksusually ones of some social privilegewho want to stop language from evolving at all costs. These are the grumps you may find dismissing gender-neutral language as ungrammatical, refusing to learn the difference between sex and gender, or lamenting the inability to throw around the word slut willy-nilly without being called sexist, like they could in the good old days. Sensing the grounds of linguistic change quaking beneath them, these humans take phenomena like vocal fry and gender-free pronouns as a spine-chilling omen that their dominance in the world is at stake. So they dig their heels in, hoping that if they can keep English as they know it from changinga futile effort, as any linguist will tell youthe social hierarchies that they so benefit from will remain intact.

Were living in an era when many of us often feel overwhelmed and silenced by the English language. But it doesnt have to be that way. We can take it back. And in this book, youre going to learn how.

But first: a history lesson. Because taking back the English language cant work unless we know where it came from in the first place. Cant cure a disease unless you figure out what causes it, you know? The good news is that the English language was not literally invented by a group of white dudes in robes sitting in a room deciding on the rules (though sometimes that is very much the case, like in Francemore on that later). For the most part, however, thats not how language works. Instead, it develops organically.