THE BOURGEOIS

Between History and Literature

FRANCO MORETTI

First published by Verso 2013

Franco Moretti 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN: 978-1-781-68085-8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moretti, Franco, 1950

The bourgeois : between literature and history / Franco Moretti.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-781-68305-7 (e-book)

1. Middle class in literature. 2. Social values in literature. I. Title.

PN56.M535M67 2013

809.93355dc23

2013004072

Typeset in Fournier by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

to Perry Anderson and Paolo Flores dArcais

Contents

A few words on some sources used frequently in the book. The Google Books corpus is a collection of several million books that allows very simple searches. The Chadwyck-Healey database of nineteenth-century fiction collects 250 extremely well-curated British and Irish novels ranging from 1782 to 1903. The Literary Lab corpus includes about 3,500 nineteenth-century British, Irish and American novels.

I also often refer to dictionaries, indicating them in parenthesis, without further specifications: the OED is the Oxford English Dictionary, Robert and Littr are French, Grimm is German, and Battaglia Italian.

1. I AM A MEMBER OF THE BOURGEOIS CLASS

Who could repeat these words today? Bourgeois opinions and idealswhat are they?

The changed atmosphere is reflected in scholarly work. Simmel and Weber, Sombart and Schumpeter, all saw capitalism and the bourgeoiseconomy and anthropologyas two sides of the same coin. I know of no serious historical interpretation of this modern world of ours, wrote Immanuel Wallerstein a quarter-century ago, in which the concept of the bourgeoisie... is absent. And for good reason. It is hard to tell a story without its main protagonist.

True, there is no necessary identification; but then, that is hardly the point. The origin of the bourgeois class and of its peculiarities, wrote Weber in The Protestant Ethic, is a process closely connected with that of the origin of the capitalistic organization of labour, though not quite the same thing. This permeability, adds Perry Anderson, sets the bourgeoisie apart

from the nobility before it and the working class after it. For all the important differences within each of these contrasting classes, their homogeneity is structurally greater: the aristocracy was typically defined by a legal status combining civil titles and juridical privileges, while the working class is massively demarcated by the condition of manual labour. The bourgeoisie possesses no comparable internal unity as a social group.

Porous borders, and weak internal cohesion: do these traits invalidate the very idea of the bourgeoisie as a class? For its greatest living historian, Jrgen Kocka, this is not necessarily so, provided we distinguish between what we could call the core of this concept and its external periphery. The latter has indeed been extremely variable, socially as well as historically; up to the late eighteenth century, it consisted mostly of the self-employed small businesspeople (artisans, retail merchants, innkeepers, and small proprietors) of early urban Europe; a hundred years later, of a completely different population made of middle- and lower-ranking white collar employees and civil servants.

The encounter of property and culture: Kockas ideal-type will be mine, too, but with one significant difference. As a literary historian, I will focus less on the actual relationships between specific social groupsbankers and high civil servants, industrialists and doctors, and so onthan on the fit between cultural forms and the new class realities: how a word like comfort outlines the contours of legitimate bourgeois consumption, for instance; or how the tempo of story-telling adjusts itself to the new regularity of existence. The bourgeois, refracted through the prism of literature: such is the subject of The Bourgeois.

2. DISSONANCES

But a much longer perspective is also possible on the antinomies of bourgeois culture. In an essay on the Sassetti chapel in Santa Trinita, which takes its cue from Machiavellis portrait of Lorenzo in the Istorie Fiorentineif you compared his light and his grave side [la vita leggera e la grave], two distinct personalities could be identified within him, seemingly impossible to reconcile [quasi con impossibile congiunzione congiunte]Aby Warburg observed that

the citizen of Medicean Florence united the wholly dissimilar characters of the idealistwhether medievally Christian, or romantically chivalrous, or classically neoplatonicand the worldly, practical, pagan Etruscan merchant. Elemental yet harmonious in his vitality, this enigmatic creature joyfully accepted every psychic impulse as an extension of his mental range, to be developed and exploited at leisure.

An enigmatic creature, idealistic and worldly. Writing of another bourgeois golden age, halfway between the Medici and the Victorians, Simon Schama muses on the peculiar coexistence that allowed

lay and clerical governors to live with what otherwise would have been an intolerably contradictory value system, a perennial combat between acquisitiveness and asceticism... The incorrigible habits of material self-indulgence, and the spur of risky venture that were ingrained into the Dutch commercial economy themselves prompted all those warning clucks and solemn judgments from the appointed guardians of the old orthodoxy... The peculiar coexistence of apparently opposite value systems... gave them room to maneuver between the sacred and profane as wants or conscience commanded, without risking a brutal choice between poverty or perdition.

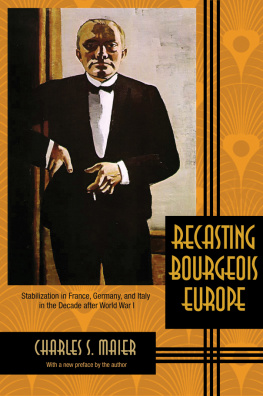

Material self-indulgence, and the old orthodoxy: Jan Steens Burgher of Delft, who looks at us from the cover of Schamas book (Figure 1): a heavy man, seated, in black, with his daughters silver-and-gold finery on one side, and a beggars discoloured clothes on the other. From Florence to Amsterdam, the frank vitality of those visages in Santa Trinita has been dimmed; the burgher is cheerlessly pinned to his chair, as if dispirited by the moral pulling and pushing (Schama again) of his predicament: spatially close to his daughter, yet not looking at her; turned in the general direction of the woman, without actually addressing her; eyes downcast, unfocused. What is to be done?

Machiavellis impossible conjunction, Warburgs enigmatic creature, Schamas perennial combat: compared to these earlier contradictions of bourgeois culture, the Victorian age appears for what it really was: a time of compromise, much more than contrast. Compromise is not uniformity, of course, and one may still see the Victorians as somewhat multicoloured; but the colours are leftovers from the past, and are losing their brilliancy. Grey, not bunt, is the flag that flies over the bourgeois century.

3. BOURGEOISIE, MIDDLE CLASS

but that middlingness was precisely what he wished to overcome: born in the middle state of early modern England, Robinson Crusoe rejects his fathers idea that it is the best state in the world, and devotes his entire life to going beyond it. Why then settle on a designation that returns this class to its indifferent beginnings, rather than acknowledge its successes? What was at stake, in the choice of middle class over bourgeois?

Next page