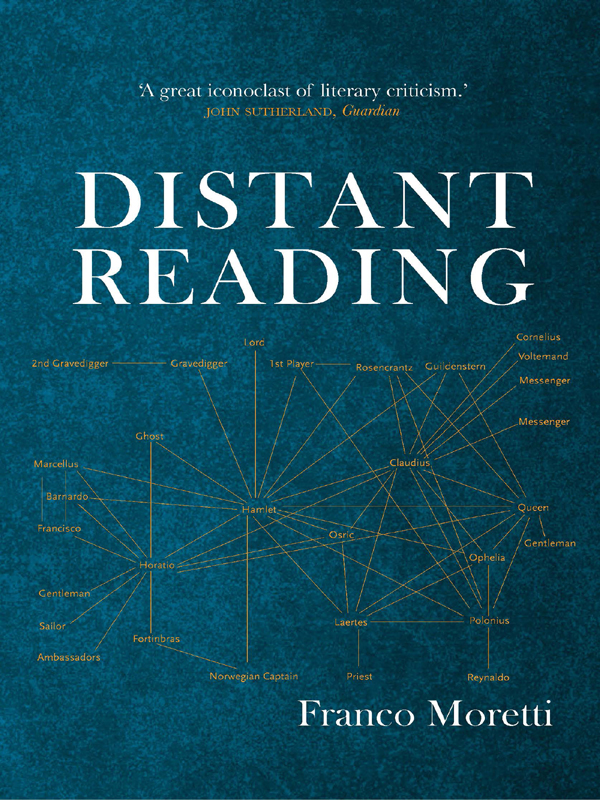

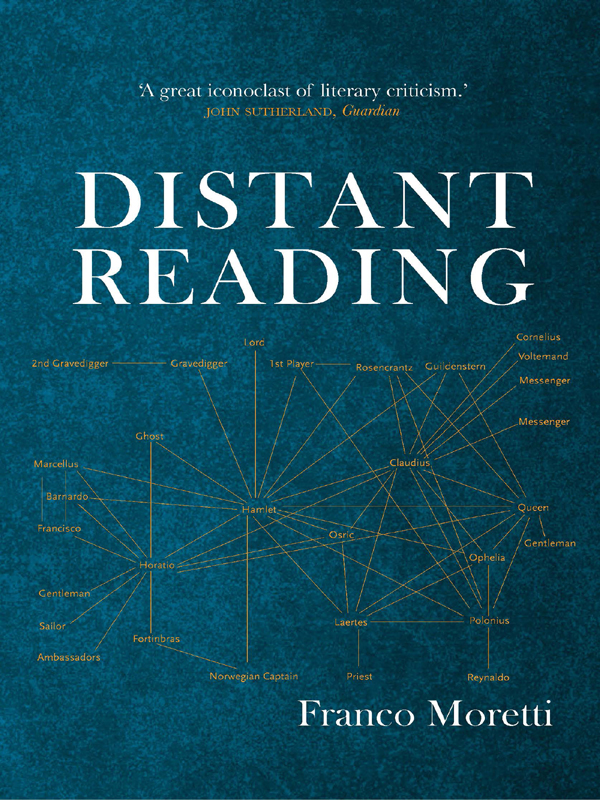

DISTANT READING

FRANCO MORETTI

First published by Verso 2013

Franco Moretti 2013

Most of the chapters in this book first appeared in the pages of New Left Review: Modern European Literature: A Geographical Sketch, JulyAugust 1994; Conjectures on World Literature, JanuaryFebruary 2000; Planet Hollywood, MayJune 2001; More Conjectures, MarchApril 2003; The End of the Beginning: A Reply to Christopher Prendergast, SeptemberOctober 2006; The Novel: History and Theory, JulyAugust 2008; Network Theory, Plot Analysis, MarchApril 2011

The Slaughterhouse of Literature appeared in Modern Language Quarterly, 61: 1, March 2000. Evolution, World-Systems, Weltliteratur appeared in Review , 3, 2005

Style, Inc.: Reflections on 7,000 Titles (British Novels, 17401850) appeared in CriticalInquiry, Autumn 2009

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN: 978-1-78168-333-0 (e-book)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moretti, Franco, 1950

[Essays. Selections]

Distant reading / Franco Moretti.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-78168-084-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-78168-112-1 (hardback : alk. paper)

1. Criticism. 2. LiteratureHistory and criticismTheory, etc. I. Title.

PN81.M666 2013

801.95dc23

2012047274

Typeset in Fournier by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

To D.A. Miller

lamico americano

Contents

In the spring of 1991, Carlo Ginzburg asked me to write an essay on European literature for the first volume of Einaudis Storia dEuropa. I had been thinking for some time about European literaturein particular, about its capacity to generate new forms, which seemed so historically uniqueand in a book I had just finished reading I found the theoretical framework for the essay: it was Ernst Mayrs Systematics and the Origin of Species, where the concept of allopatric speciation (allopatry = a homeland elsewhere) explained the genesis of new species by their movement into new spaces. I took forms as the literary analogue of species, and charted the morphological transformations triggered by European geography: the differentiation of tragedy in the seventeenth century, the novels take-off in the eighteenth, the centralization and then fragmentation of the literary field in the nineteenth and twentieth. The notion of European literature, singular, was replaced by that of an archipelago of distinct yet close national cultures, where styles and stories moved quickly and frequently, undergoing all sorts of metamorphoses. Creativity had found an explanation that made it seem easy, and almost inevitable.

This was a happy essay. Aimed at a non-academic audience, and on such a large topic, it asked for a balance between the abstraction of model-building and the vividness of individual examplesa scene, a character, a line of versethat would make it worth reading in the first place. Somehow, I found the right tone; possibly, because of my total reliance on the canon of European masterpieces (as a colleague pointed out, the word great seemed ubiquitous in the essay; and it was, I used it fifty-one times!). The canon allowed for comparative analysis to take place: Shakespeare and Racine, the conte philosophique and the Bildungsroman, the Austrians and the avant-gardes ... As the years went by, I would move increasingly away from this idea of literature as a collection of masterpieces; and in truth, I feel no nostalgia for what it meant. But the conceptual cogency that a small set of texts allows forthat, I do miss.

This was a happy essay. Evolution, geography, and formalismthe three approaches that would define my work for over a decadefirst came into systematic contact while writing these pages. I felt curious, full of energy; I kept studying, adding, correcting. I learned a lot, and one day I even had the first, confused idea of an Atlas of literature. And then, I was writing in Italian; for the last time, as it turned outthough, at the time, I didnt know it. In Italian, sentences run easier; details, and even nuances, seem to emerge all by themselves. In English, it would all be different.

Years ago, Denis de Rougement published a study entitled Twenty-eight Centuries of Europe; here, readers will only find five of them, the most recent. The idea is that the sixteenth century acts as a double watershedagainst the past, and against other continentsafter which European literature develops that formal inventiveness that makes it truly unique. (Not everybody agrees on this point, however, and so we will begin by comparing opposite explanatory models.) As for examples, the limited space at my disposal has been a great help; I have felt free to focus on a few forms, and make definite choices. If the description will not be complete (but is that ever the case?), at least it will not lack clarity.

1. A MODEL: UNIFIED EUROPE

Those were beautiful times, those were splendid times, the times of Christian Europe, when one Christianity inhabited this continent shaped in human form, and one vast, shared design united the farthest provinces of this spiritual kingdom. Free from extended worldly possessions, one supreme ruler held together the great political forces...

What you have just read are the first sentences of Christianity, or Europe, the celebrated essay written by Novalis in the very last months of the eighteenth century. As its underlying structure, a very simple, very effective equation: Europe is Christianity, and Christianity is unity. All threats to such unitythe Reformation, of course; but also the modern nation states, economic competition, or untimely, hazardous discoveries in the realm of knowledgethreaten Europe as well, and induce Novalis, who is all but a moderate thinker, to approve of Galileis humiliation, or to sing a hymn in praise of the Jesuitswith an admirable foresight and constance, with a wisdom such as the world had never seen before... a Society appeared, the equal of which had never been in universal history... Here, let me just point out how this intransigent conception of European unityone Christianity, one design, one ruleris also the backbone of the only scholarly masterpiece devoted to our subject: Ernst Robert Curtiuss European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, published in 1948. This work aims at grasping European literature as a unified whole, and to found such unity on the Latin tradition, reads Auerbachs review.

Onto Novaliss spatial order (Rome as the centre of Europe), Curtius superimposes the temporal sequence of Latin topoi, with its fulcrum in the Middle Ages, which again leads to Rome. Europe is unique because it is one, and it is one because it has a centre: Being European means having become cives romani, Roman citizens. And heres the rub, of course: because Curtiuss Europe is not really Europe, but ratherto use the term so dear to himRomania. It is a single space, unified by the LatinChristian spirit that still pervades those universalistic works (The Divine Comedy,

Next page