DEAN NIMMER

Foreword by Gregory Amenoff

Chairman of Visual Arts Division,

Columbia University

WATSON-GUPTILL PUBLICATIONS / BERKELEY

Text copyright 2008 by Dean Nimmer

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Watson-Guptil Publications, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.watsonguptill.com

Watson-Guptill Publications and the Watson-Guptill Publications colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nimmer, Dean.

Art from intuition : overcoming your fears and obstacles to making art / by Dean Nimmer; foreword by Gregory Amenoff.

p. cm.

1. Art--Technique. I. Title.

N7430.5.N555 2008

701.15--dc22

2007042541

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8230-9750-0

eBook ISBN: 978-0-307-82937-5

Cover design by Rodrigo Corral

Cover photo by Dean Nimmer

Interior design by Rodrigo Corral Design/Jason Ramirez

v3.1

This book is dedicated to my children, Christopher, Corey, and Lilly, and to my granddaughter Kaitlyn.

Contents

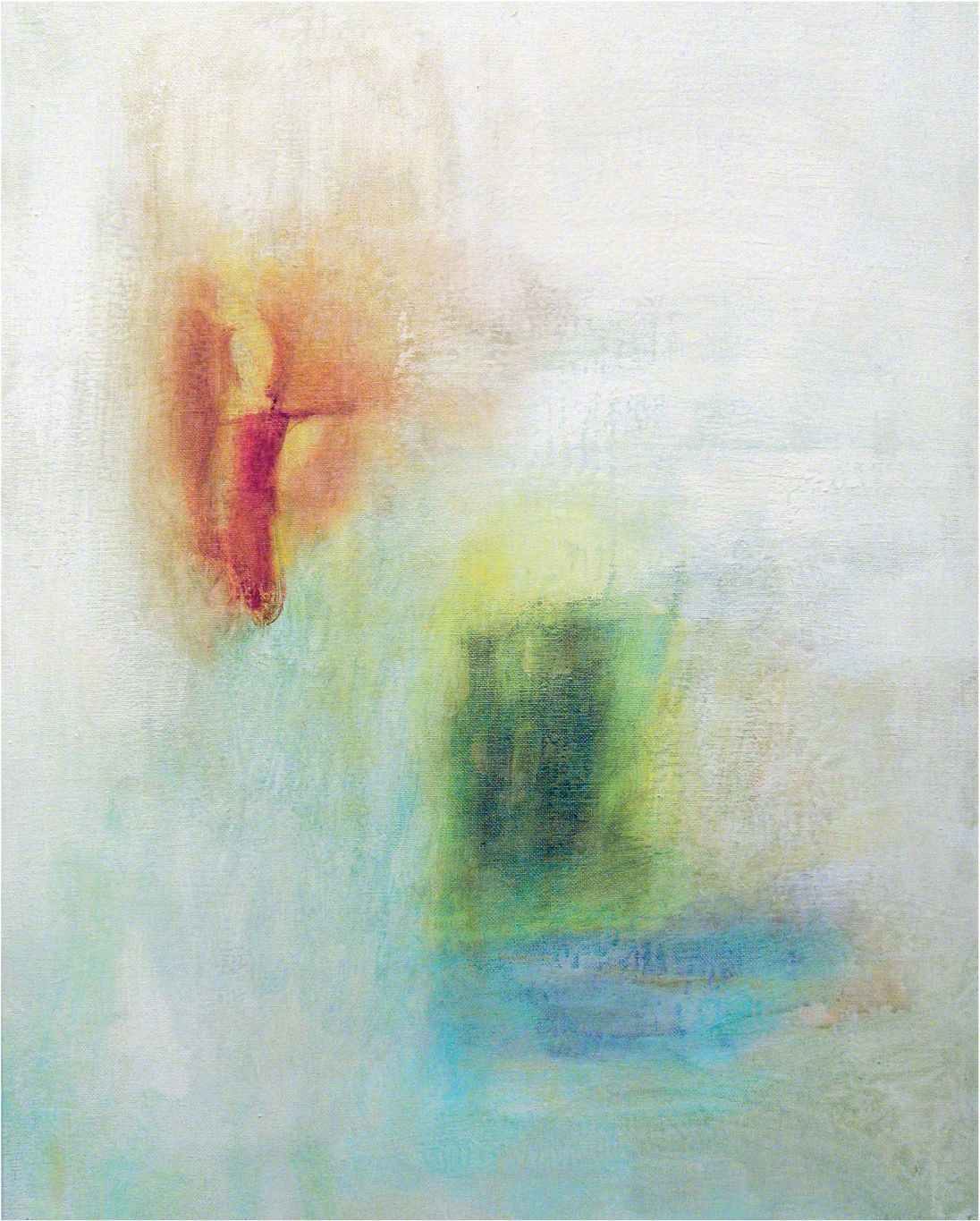

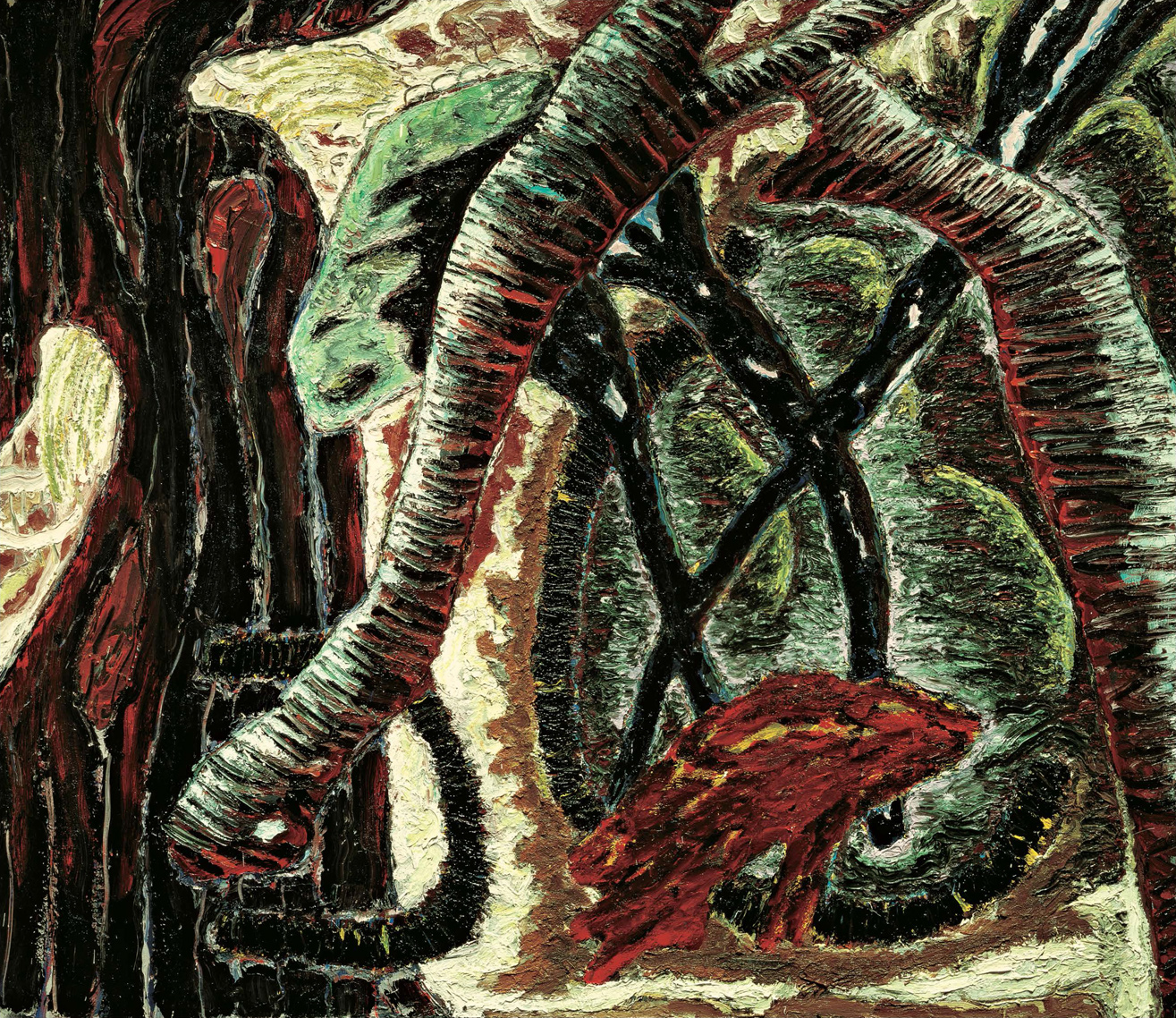

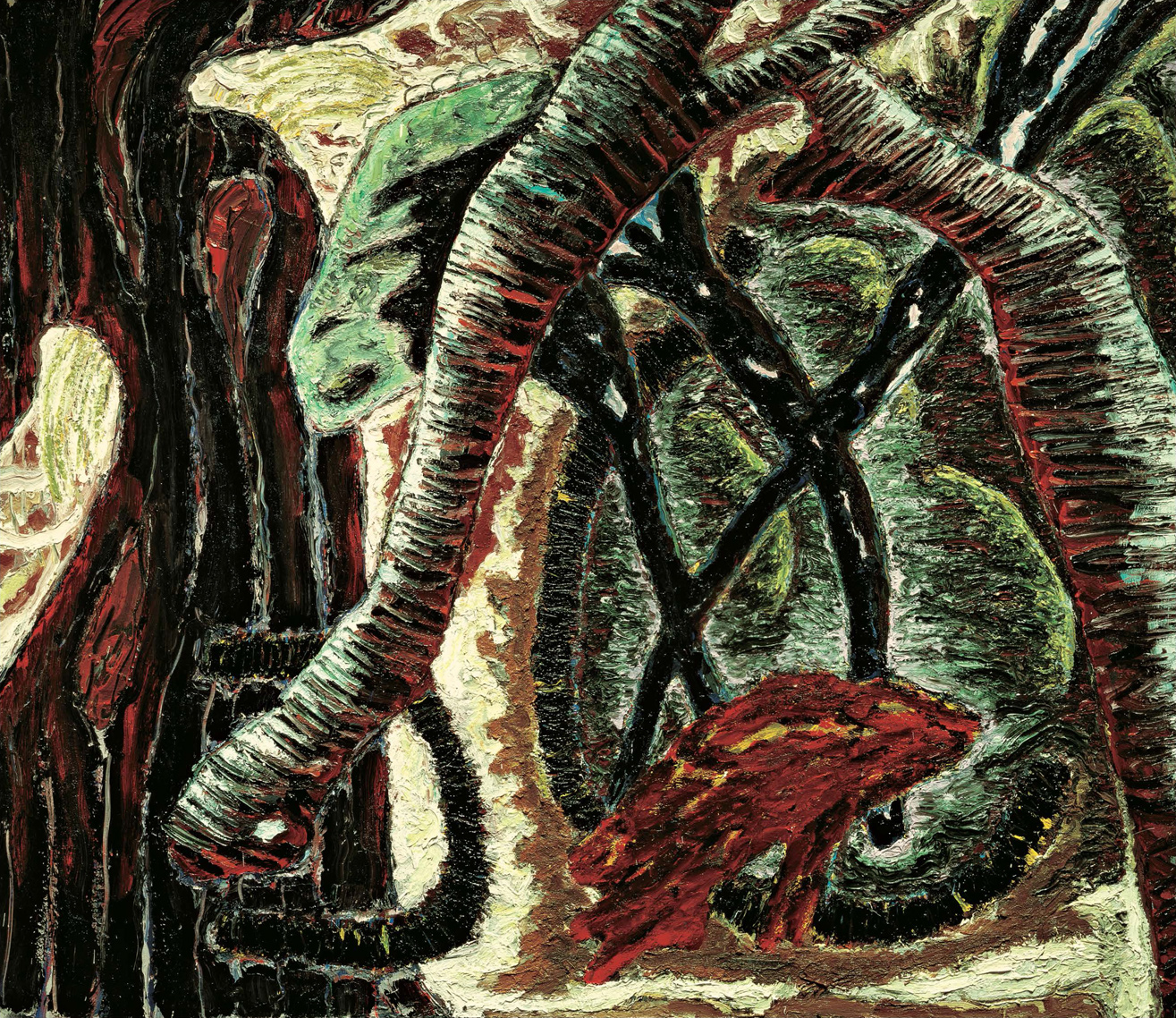

Solstice , oil on canvas, by Gregory Amenoff.

Foreword

In-tu-i-tion: 1.) last nights dream + impulsive idea + weird uncle +

too much coffee + mystical vision + unrequited desire = Intuition

This faux equation may be as close as one can get to defining the creative jump that is called intuition. It would seem plain wrong-headed in the foreword to a book on inventiveness to use a dictionary definition for such an elusive concept. Intuition, after all, is a notion that defies rationality, yet the intuitive process is not without its own logic. In fact, I would argue that works of art offer the viewer a portal that opens directly into the intuitive process of the artist. Although the art experience is multifaceted, it depends to a large measure on the intuitive space shared by the viewer and the creator. This book relies on imagination to help readers find the freedom to exercise their own innate intuitive spirit and to enter into the intuitive space of others.

For many, the notion of the artists creative process is shaped by the Hollywood image of the isolated, mad genius stabbing the air for ideas and then suddenly realizing them, fully formed, on a canvas, a piece of stone, or in brisk musical notation. We all know that films cant help but stereotype their subjects, and these often romanticized characterizations seem to substitute affectations for what is really a complex and amazing process. Let me suggest instead a more realistic version of the artist in the midst of a creative process.

The artist enters the studio, armed with an idea for a painting (or sculpture, song, etc.). Often, the idea appears to the inner eye somewhat formed, but until it is physically manifest, its outline is, at best, a bit cloudy. Marks are made, colors are applied, and the object is set in motion. The creative spark is now lit, but the fire needs tending. It is instinct and the willingness to trust it that now come into play. As counterintuitive as it seems, intuition involves countless subjective considerations and small judgments. Judgments? Yes! Not rational judgments or evaluations, but intuitive decisionseach one propelling the work of art beyond its limits. The artist must then trust (or distrust) those leaps, only to leap again and again, possibly in different and even contradictory directions. Imagine Jackson Pollock moving and dancing with the paint, using his eye and his intuition to direct his hand in order to bring a new world into clear view. The creative spark allowed him to beginto see something that he felt needed to be rendered visiblebut intuition and the audacity to trust it propelled the paintings into greatness and, finally, into history.

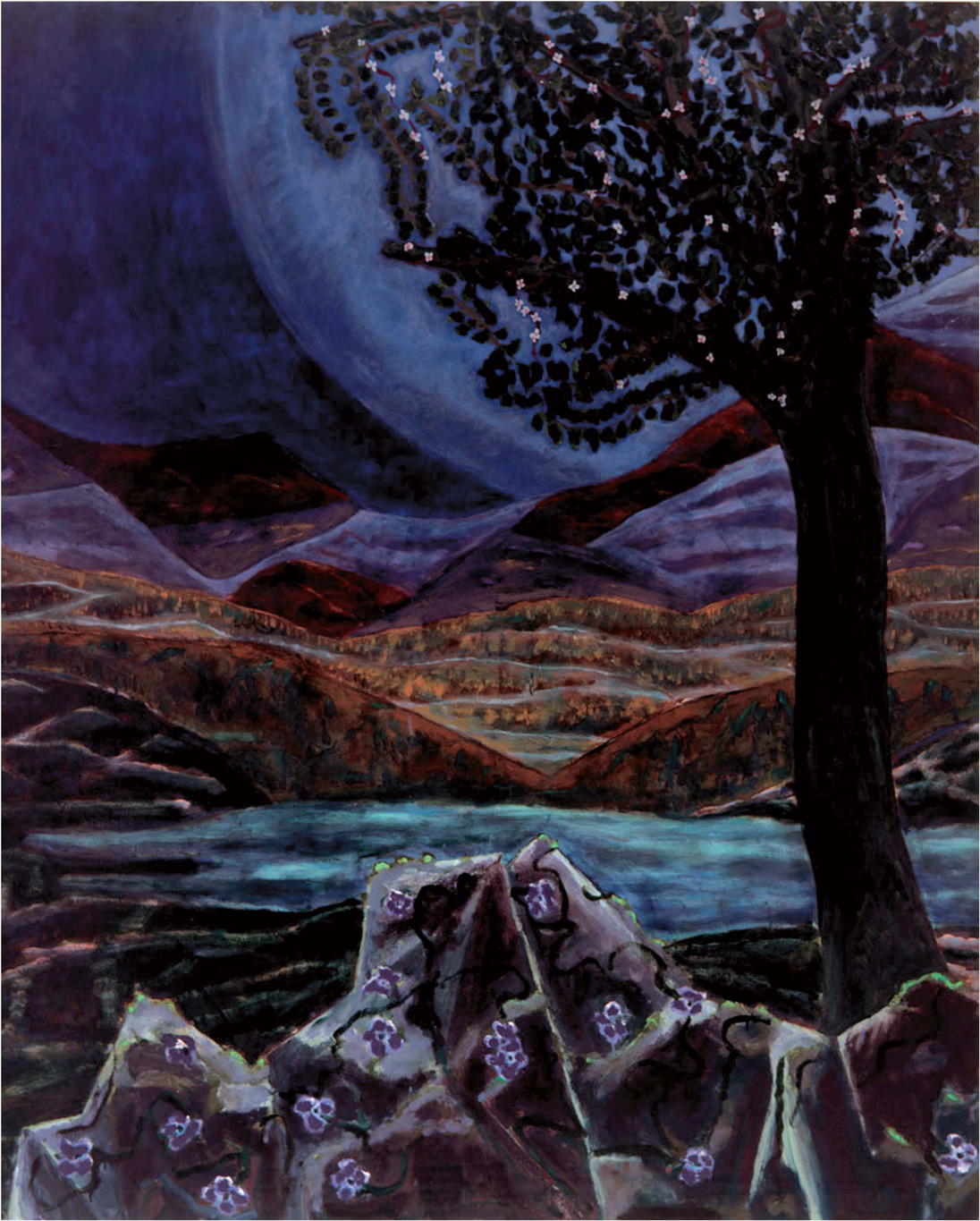

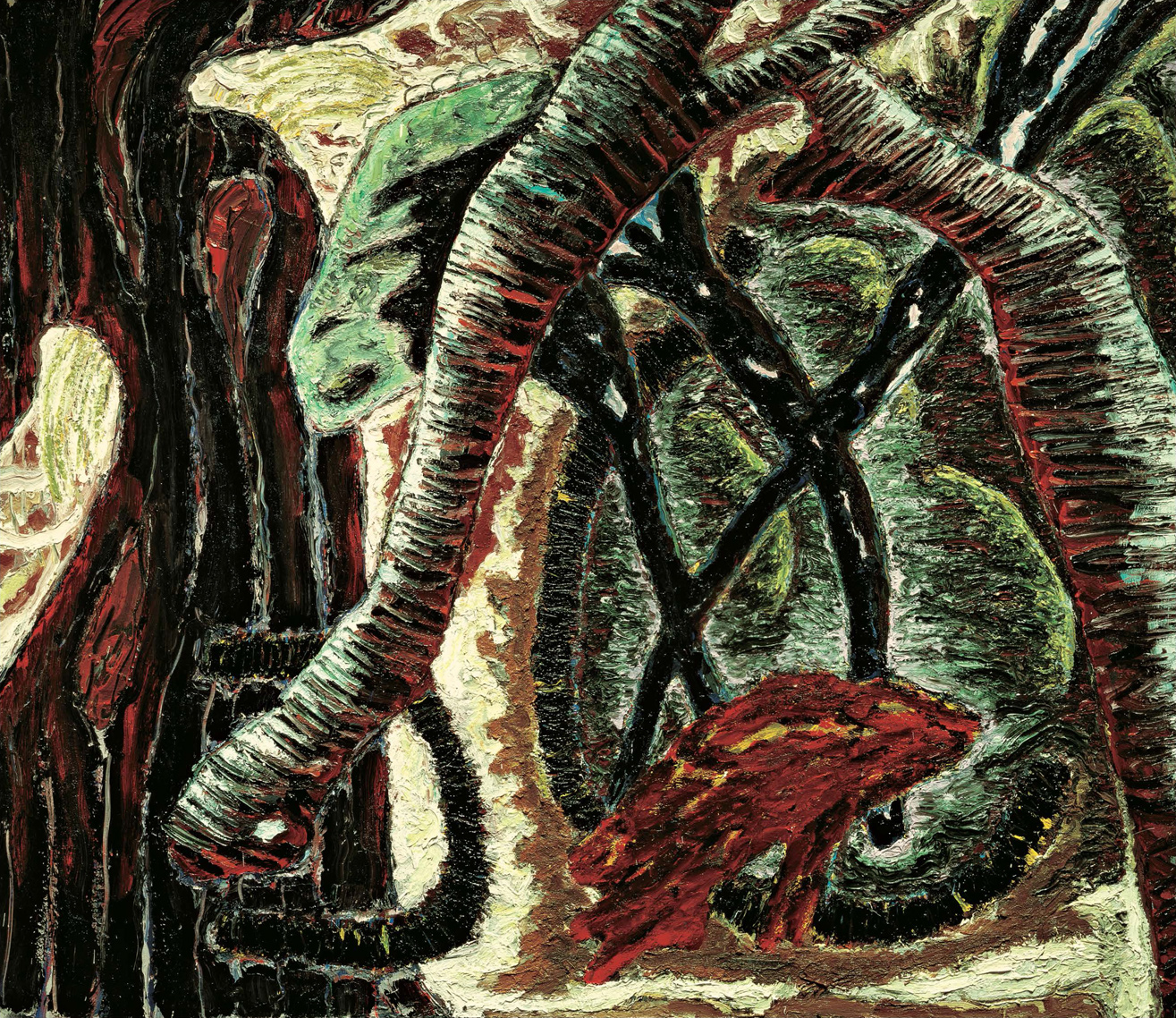

Tramontone , oil on canvas, by Gregory Amenoff. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

But intuition does not necessarily live only in those almost trancelike moments of creativity; it also comes into play upon reevaluation. The day after, perhaps things dont look so rosy and magical; decisions made earlier might look weak or flawed. Then the artist must again rely on his or her intuition to adjust, to destroy, and to rebuilduntil the final marks are made and the image is allowed to emerge from those countless small judgments and take on a life of its own.

Artists must intuit, and they must trust their instincts, thereby taking a huge risk. That risk can result in outright failure at worst, or it may yield the artist a grand success, but without the development of the intuitive self and a willingness to embrace and finally trust it, little of consequence can be accomplished. Having said that, the insights in this book are meant to speak to an audience much more broad and varied than the world populated by artists. The projects within these pages can speak to all of uscoaxing us to discard our fears of creativity and replace them with faith in an intuitive, inventive processone that can transform the mundane into the remarkable and the blank canvas into something of great personal value.

Gregory Amenoff

New York City 2006

Gregory Amenoff is Chairman of the Visual Arts Division and the Eve and Herman Gelman Professor of Visual Art at Columbia University in New York City. He served as President of the National Academy of Design from 2001 to 2005 and is currently Curator Governor of the Cue Art Foundation.

View from Beijing , collage and oil paint, by Dean Nimmer.