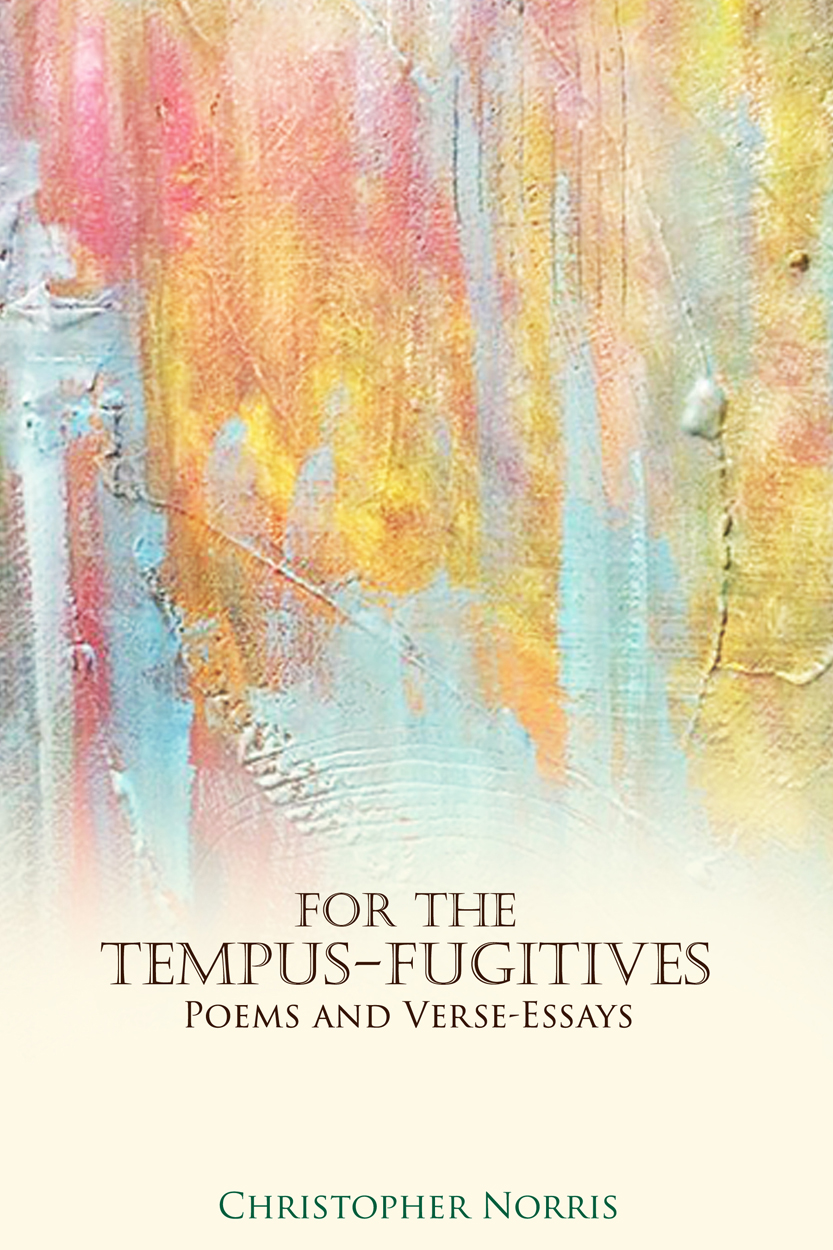

For the Tempus-Fugitives

For the Tempus-Fugitives  General Editor: David Jonathan Y. Bayot For Val CHRISTOPHER NORRIS For the Tempus-Fugitives Poems and Verse-Essays

General Editor: David Jonathan Y. Bayot For Val CHRISTOPHER NORRIS For the Tempus-Fugitives Poems and Verse-Essays  Copyright Christopher Norris, 2017. The right of Christopher Norris to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 978-1-78284-432-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-78284-430-3 (ePub) ISBN 978-1-78284-431-0 (Kindle) Published and distributed in the Philippines under ISBN 978-971-555-644-6 by De La Salle University Publishing House 2401 Taft Avenue, 0922 Manila, Philippines This edition published and distributed under ISBN 978-1-84519-867-1 in

Copyright Christopher Norris, 2017. The right of Christopher Norris to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 978-1-78284-432-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-78284-430-3 (ePub) ISBN 978-1-78284-431-0 (Kindle) Published and distributed in the Philippines under ISBN 978-971-555-644-6 by De La Salle University Publishing House 2401 Taft Avenue, 0922 Manila, Philippines This edition published and distributed under ISBN 978-1-84519-867-1 in

Great Britain in 2017 by SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

PO Box 139, Eastbourne BN24 9BP and in North America by SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS

ISBS Publisher Services

920 NE 58th Ave #300, Portland, OR 97213, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover Design: John David Roasa.

Cover Image: Bernie Lira. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Norris, Christopher For the tempus-fugitives : poems and verse-essays / Christopher Norris [Manila] : De La Salle University Publishing House, 2017. 2017 254 pages ; 23 cm. (Critical Voices) ISBN: 978-971-555-644-6 (pbk), in the Critical Voices series 1. I. Title.  Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.

Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.  Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.

Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.

Printed by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall, UK. CONTENTS Preface I It is not hard to find plausible reasons for the decline in popularity of the verse-essay, along with its (slightly) less formal sibling the verse-epistle, over the past century and more. The genre had its heyday in the eighteenth century among poets like Dryden, Pope, Johnson, Swift, and many nowadays less-known figures who used it to discuss all sorts of topics from politics and history to philosophy, religion, morals, literature, science, and their own day-to-day lives. This they did for the most part in rhymed and metrically regular verse with iambic pentameter very much the norm. There was also a strong preference for rhyming couplets with frequent use of end-stopping, i.e., with a more or less emphatic end-of-line metrical halt to the couplet just where the sentence or grammatical construction likewise concludes. The manner was thus highly formal, at least to present-day tastes, though in the right hands capable of great tonal, rhythmic, and stylistic variety, as will soon strike any responsive reader of a well-edited selection.

Above all it was capable of doing thingsarguing, reasoning, debating, controverting, reflecting on matters particular and generalin a way that very largely disappeared from English poetry with the advent of Romanticism and later movements of thought, whether post-, neo-, or (like mainstream literary modernism) officially anti-Romantic. I think that those things are still worth doing and that it is only through tunnel-vision or the set of generic filters imposed by the Romantic-to-Modernist viewpoint that readers now tend to think of poetryreal poetryas simply or properly not in that line of business. William Empson, one of its finest practitioners, coined the word argufying to describe what he thought of as the right way to carry this off without sacrificing vigorous argument to the requirements of disciplined yet lively versification or (just as important) the demands of verse to those of argumentative relevance or point. His own verse-practice offered the best working definition: a mode (something more than style) of reasoning that doesnt try for anything like deductive or strict demonstrative rigor but which none the less seeks the readers assent on broadly rational, reasonable, or common-sense terms. At the same timeand quite compatibly with thatthe verse should have enough formal structure to carry on some fairly lengthy trains of thought without sagging or losing impetus while also having sufficient rhythmic variety and unexpected or striking turns of rhyme to keep the reader actively engaged. As hardly needs saying there has to be a constant interplay or tension between meter and natural speech-rhythms such that the two never perfectly coincide but set up an asynchronous counterpoint that again helps to stimulate ear and mind.

Empson managed all this to marvelous effect, though perhaps the best examples are to be found in his later, more relaxed or conversational poems. His better-known early pieceswritten while still an undergraduate at Cambridge and very consciously imitating Donneare often so intellectually taxing or wiredrawn (so conceited, as Johnson said of the metaphysical poets) that they dont fully meet the above (albeit rough) specifications. What is crucial is that the verse should carry the argument along in a natural-sounding way while also pointing up salient details, introducing nuances of tone or implication, and sometimes (especially through inventive or unusual rhyme-words) sending thought off in a new direction that very likely wouldnt have occurred to a prose writer. This is how it works in the best eighteenth-century instances and how I have tried to make it work here, although with how much success of course only the reader can say. One thing that definitely wont work for contemporary poets or readers is that heavily end-stopped line so characteristic of Pope and Dryden when delivering some weighty generalization, drawing some sententious moral conclusion, or skewering some literary rival. To modern ears it has an insufferable air of arrogance or assumed superior wisdom, as well as an artificial elegance all too redolent of social-cultural privilege.

My poems depart so far from that style as to take enjambment as the norm along with a high proportion of lengthy sentences, complex syntactic structures, multiple subordinate clauses, and a liberal use of devicessuch as extended analogythat likewise hold out against any sense of premature or forceful closure. Giorgio Agamben has raised thisor something like itto a high point of poetic-philosophical principle by maintaining (with reference to Dante) that poetry just is, or is most essentially, language of the kind where syntax and meter fail to coincide. So if closure, or bringing poems to an end, has often been a problem for poets it is because the final word or syllable of a poems last line is the place where that enlivening tension, thus far sustained by enjambment, is itself of necessity brought to an end with syntax and meter more or less forcibly synchronized. I wouldnt go so far as Agamben in making their disjunction the sine qua non of authentic poetry and their convergence a source of inevitable crisis or breakdown. All the same I would accept the more moderate claim that such effects of formal non-synchrony or irresolution play a large role in distinguishing poetic from prose discourse. One way of looking at modernism in English poetry is to trace it back to the Romantic revoltmost vehemently expressed by Wordsworthagainst poetic diction of the kind (especially the eighteenth-century kind) that foregrounded that distinction.

Next page

![Norris - Clybourne Park: [a play]](/uploads/posts/book/223649/thumbs/norris-clybourne-park-a-play.jpg)

For the Tempus-Fugitives

For the Tempus-Fugitives  General Editor: David Jonathan Y. Bayot For Val CHRISTOPHER NORRIS For the Tempus-Fugitives Poems and Verse-Essays

General Editor: David Jonathan Y. Bayot For Val CHRISTOPHER NORRIS For the Tempus-Fugitives Poems and Verse-Essays  Copyright Christopher Norris, 2017. The right of Christopher Norris to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 978-1-78284-432-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-78284-430-3 (ePub) ISBN 978-1-78284-431-0 (Kindle) Published and distributed in the Philippines under ISBN 978-971-555-644-6 by De La Salle University Publishing House 2401 Taft Avenue, 0922 Manila, Philippines This edition published and distributed under ISBN 978-1-84519-867-1 in

Copyright Christopher Norris, 2017. The right of Christopher Norris to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. ISBN 978-1-78284-432-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-78284-430-3 (ePub) ISBN 978-1-78284-431-0 (Kindle) Published and distributed in the Philippines under ISBN 978-971-555-644-6 by De La Salle University Publishing House 2401 Taft Avenue, 0922 Manila, Philippines This edition published and distributed under ISBN 978-1-84519-867-1 in Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.

Typeset & designed by De La Salle University Publishing House.