Acknowledgements

I owe a great debt to New Zealands Department of Conservation (DOC) and to the many DOC officers, conservation workers, hut wardens, track workers and office staff who do such a wonderful job of looking after the natural world through which we trampers tramp. This debt extends to the peoples and government of New Zealand who value and protect their natural environments.

Thank you to the many friendly, helpful and informative New Zealanders who aided my research particularly to staff at the National Archives, the Alexander Turnbull Library, the Auckland Central City Library and the University of Auckland, and to DOC employees Ken Bradley and Brian Dobbie for answering the questions that no one else could answer.

For their tips, company, assistance and laughter, I am deeply indebted to my fellow trampers, particularly: Gill Davidson and Sarah Gray; Ian Beadle, Matthew Cooper and Dominic Morris; Jane Palmer, Shane Hona and Leon (wherever you are); Steve Carr and Ben Stewart from Wades Landing Outdoors; honorary trampers Stewart and Robyn; and the unforgettable Boys from Murupara Steve Malaquin, Steve Teddy, Glen Craddock and Jason, Glen, Colin and Blair. My heartfelt thanks also to the friends who helped me on the journey between tracks, but particularly to Kanaka Ramyasiri, and Chris and Kane Dooley.

Thank you to older friends who have shaped parts or all of what follows, not least by diligently reading drafts and being brave enough to give me their honest opinion: Tamsen Harward, Karen Scardifield, Jonathan Medcalf, Emil Bernal, Steve Hill, Helen Willis and Gemma Pearson. Any remaining errors are entirely mine. Thanks too to my publishers, Simon Lowe at Know The Score Books and Ian Watt at Exisle, who believed in this book and made it happen. And humblest thanks to my parents, to whom this book is dedicated, for absolutely everything.

Finally, but crucially, thank you from the bottom of my heart to everyone who has ever tramped or will go tramping in New Zealand whilst leaving no trace that they were there.

Taking care of things

Personal safety

I did not die or sustain any serious injuries in researching and writing this I book, but there were many times when I was acutely aware of how easy it would be to do either, or both.

My hope is that as you read this book you will be entertained by what the Great Walks and the backcountry of New Zealand have to offer and that, along the way, trampers and prospective trampers will pick up lots of practical information, almost without noticing it. However, what follows is not a guidebook, nor is it a comprehensive guide on what to take, how to prepare or other ways to avoid the inevitable dangers inherent in tramping.

Sadly, there are regular reports of injuries and fatalities in New Zealands backcountry. No one imagines that they will be the subject of such a report, yet people still make the seemingly small decisions that can lead to this. Decisions about what food and clothing to take. Or what boots to wear.

Personal safety whilst tramping depends on a number of factors: knowing where youre going; understanding what to expect of the terrain; knowing what facilities will be available and what wont; knowing how to stay warm, well fed and hydrated; anticipating all possible types of weather (of which New Zealand has a breathtaking and volatile array); understanding basic first aid; taking the right equipment, knowing how to use it ... and so on.

If youre preparing to tramp, please make sure you get all the information you need to take good care of yourself out on the track. A great place to start is with the New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) website at www.doc.govt.nz/Explore/Safety.asp.

Other useful websites include:

NZ Mountain Safety Council (www.mountainsafety.org.nz)

New Zealand weather (www.metservice.co.nz)

Avalanche warnings (www.avalanche.net.nz)

NZ Land Search and Rescue (www.nzlsar.org.nz)

NZ Search & Rescue Council distress beacon information (www.beacons.org.nz)

Finally and as importantly make sure that you notify the local DOC office of your intentions before you head into the bush and that you add your details into each intentions book en route. These books are found in all DOC huts, as well as at some car parks and information shelters. You should fill in as much detail as possible about your planned route, dates, times, size of party etc. It is all too easy to get into trouble in the backcountry, where rescue is only possible if someone knows to come looking and knows where to look.

Environmental care

Health and safety does not start and end with the tramper. The natural environment must survive your trip too. The aim is to leave no trace of yourself behind. This is not always achievable, given that youre likely to encounter mud and leave a few footprints in it. But footprints should be all.

The number of different ways in which a tramper can damage the environment that he or she is enjoying is truly depressing. Worse still, few of us instinctively know and understand each of the impacts we can have on the natural environment as we tramp through it.

The good news is that it doesnt take long to learn a great deal. Again, a great place to start is on DOCs website at www.doc.govt.nz/Explore/NZ-Environmental-Care-Code.asp.

For those travelling to New Zealand from other countries, your opportunities to protect New Zealands natural environments begin even before you arrive. In particular, dont take any food or plants etc. with you and make sure you clean tramping boots and other equipment carefully, so that you dont inadvertently import bits of another country. Fortunately, New Zealands airports are equipped with customs and agricultural/quarantine officers. On arrival, after your passport has been checked, your shoes and other equipment will be too. If in doubt, declare any potentially muddied items you may have. If you havent already cleaned them, local officials are fully equipped to do so.

Happy and responsible tramping.

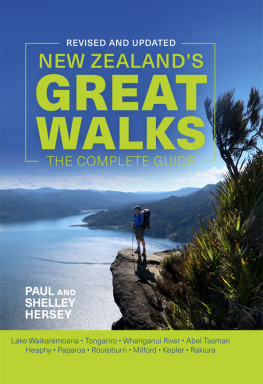

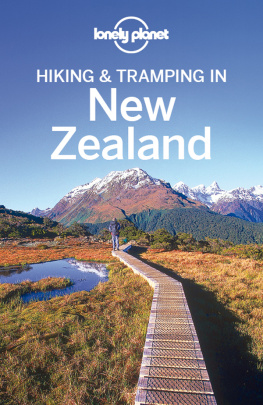

New Zealand Locations

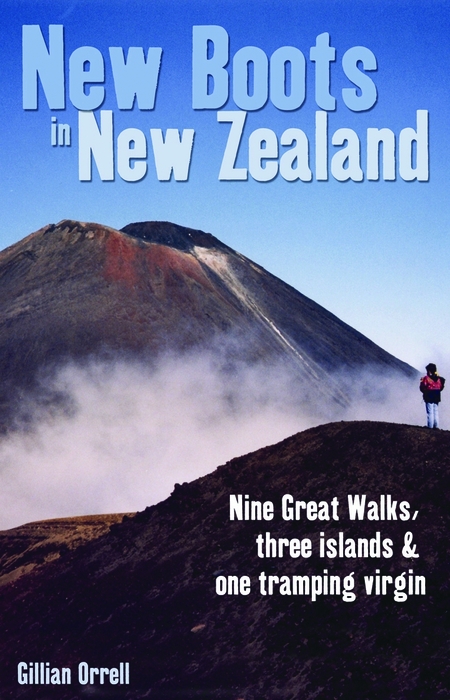

Image A

1

Wilderness awaits

One dark evening in February I sank down exhausted in front of the nine oclock news and watched an item from New Zealand appear amongst the headlines. Severe and prolonged rainfall had caused the Whanganui River to flood. Footage showed buildings, animals and people being flung out to sea by a body of water that ought not to be called a river. Cattle were being catapulted along with surprised expressions on their faces. Barns and fences were in hot pursuit of their livestock. Locals were describing this as the worst flood theyd ever known. They looked and sounded like people who had seen many floods, who called a spade a spade and who were used to getting on with things, rather than talking to TV crews.

I watched with open mouth. I almost found the energy to sit up straight. Id seen flood footage before, sometimes from Japan, sometimes from America, sometimes from the M40. But in the eighteen years since the French secret service sank the