BY ADRIENNE RICH Later Poems: Selected and New, 19712012 Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 20072010 A Human Eye: Essays on Art and Society, 19972008 Poetry & Commitment: An Essay Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth: Poems 20042006 The School Among the Ruins: Poems 20002004 What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems 19502001 Fox: Poems 19982000 Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations Midnight Salvage: Poems 19951998 Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 19911995 Collected Early Poems 19501970 An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 19881991 Times Power: Poems 19851988 Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 19791985 Your Native Land, Your Life: Poems Sources A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far: Poems 19781981 On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 19661978 The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 19741977 Twenty-One Love Poems Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution Poems: Selected and New, 19501974 Diving into the Wreck: Poems 19711972 The Will to Change: Poems 19681970 Leaflets: Poems 19651968 Necessities of Life Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 19541962 The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems A Change of World COLLECTED POEMS 1950-2012

BY ADRIENNE RICH Later Poems: Selected and New, 19712012 Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 20072010 A Human Eye: Essays on Art and Society, 19972008 Poetry & Commitment: An Essay Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth: Poems 20042006 The School Among the Ruins: Poems 20002004 What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems 19502001 Fox: Poems 19982000 Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations Midnight Salvage: Poems 19951998 Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 19911995 Collected Early Poems 19501970 An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 19881991 Times Power: Poems 19851988 Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 19791985 Your Native Land, Your Life: Poems Sources A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far: Poems 19781981 On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 19661978 The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 19741977 Twenty-One Love Poems Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution Poems: Selected and New, 19501974 Diving into the Wreck: Poems 19711972 The Will to Change: Poems 19681970 Leaflets: Poems 19651968 Necessities of Life Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 19541962 The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems A Change of World COLLECTED POEMS 1950-2012  ADRIENNE

ADRIENNE

RICH  Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. CONTENTS BY CLAUDIA RANKINE In answer to the question Does poetry play a role in social change? Adrienne Rich once answered: Yes, where poetry is liberative language, connecting the fragments within us, connecting us to others like and unlike ourselves, replenishing our desire. [I]n poetry words can say more than they mean and mean more than they say. In a time of frontal assaults both on language and on human solidarity, poetry can remind us of all we are in danger of losingdisturb us, embolden us out of resignation. There are many great poets, but not all of them alter the ways in which we understand the world we live in; not all of them suggest that words can be held responsible.

Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. CONTENTS BY CLAUDIA RANKINE In answer to the question Does poetry play a role in social change? Adrienne Rich once answered: Yes, where poetry is liberative language, connecting the fragments within us, connecting us to others like and unlike ourselves, replenishing our desire. [I]n poetry words can say more than they mean and mean more than they say. In a time of frontal assaults both on language and on human solidarity, poetry can remind us of all we are in danger of losingdisturb us, embolden us out of resignation. There are many great poets, but not all of them alter the ways in which we understand the world we live in; not all of them suggest that words can be held responsible.

Remarkably, Adrienne Rich did this and continues to do this for generations of readers. In her Collected Poems 19502012 we have a chronicle of over a half century of what it means to risk the self in order to give the self. Richs desire for a transformative writing that would invent new ways to be, to see, and to speak drew me to her work in the early 1980s while I was a student at Williams College. Midway through a cold and snowy semester in the Berkshires, I read for the first time James Baldwins 1962 The Fire Next Time and two collections by Rich, her 1969 Leaflets and her 19711972 Diving into the Wreck . In Baldwins text I underlined the following: Most people guard and keep; they suppose that it is they themselves and what they identify with themselves that they are guarding and keeping, whereas what they are actually guarding and keeping is their system of reality and what they assume themselves to be. One can give nothing whatever without giving oneselfthat is to say, risking oneself.

Richs interrogation of the guarding of systems was the subject of everything she wrote in the years leading up to my first encounter with her work. Leaflets , Diving into the Wreck , and The Dream of a Common Language were all examples of her interrogation, as were her other works, all the way to her final poems in 2012. And though I did not have the critic Helen Vendlers experience upon encountering RichFour years after she published her first book, I read it in almost disbelieving wonder; someone my age was writing down my life. Here was a poet who seemed, by a miracle, a twin: I had not known till then how much I had wanted a contemporary and a woman as a speaking voice of lifeI was immediately drawn to Richs interest in what echoes past the silences in a life that wasnt necessarily my life. In my copy of Richs essay When We Dead Awaken, the faded yellow highlighter still remains recognizable on pages after more than thirty years: Both the victimization and the anger experienced by women are real, and have real sources, everywhere in the environment, built into society, language, the structures of thought. As a nineteen-year-old, I read in both Rich and Baldwin a twinned dissatisfaction with systems invested in a single, dominant, oppressive narrative.

My initial understanding of feminism and racism came from these two writers in the same weeks and months. Rich claimed that Baldwin was the first writer I read who suggested that racism was poisonous to white as well as destructive to Black people (Blood, Bread, and Poetry: The Location of the Poet [1984]). It was Rich who suggested to me that silence, too, was poisonous and destructive to our social interactions and self-knowledge. Her understanding that the ethicacy of our personal relationships was dependent on the ethics of our political and cultural systems was demonstrated not only in her poetry but also in her essays, interviews, and in conversations like the extended one she conducted with the poet and essayist Audre Lorde. Despite the vital friendship between Lorde and Rich, or perhaps because of it, both poets were able to question their own everyday practices of collusion with the very systems that oppressed them. As self-identified lesbian feminists, they openly negotiated the difficulties of their very different racial and economic realities.

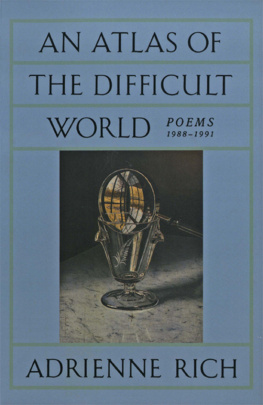

Stunningly, they showed us that, if you listen closely enough, language is no longer personal, as Rich writes in Meditations for a Savage Child, but stains and is stained by the political. In the poem Hunger (19741975), which is dedicated to Audre Lorde, Rich writes, Im wondering / whether we even have what we think we have / even our intimacies are rigged with terror. / Quantify suffering? My guilt at least is open, / I stand convicted by all my convictionsyou, too And as if in the form of an answer, Lorde wrote in The Uses Of Anger: Women Responding to Racism, an essay published in 1981, I cannot hide my anger to spare your guilt, nor hurt feelings, nor answering anger; for to do so insults and trivializes all our efforts. Guilt is not a response to anger; it is a response to ones own actions or lack of action. By my late twenties, the early 1990s, I was in graduate school at Columbia University and came across Richs recently published An Atlas of the Difficult World. I approached the volume thinking I knew what it would hold but found myself transported by Richs profound exploration of ethical loneliness.

Rich called forward voices created in a precarious world. And though the term ethical loneliness would come to me years later from the work of the critic Jill Stauffer, I understood Rich to be drawing into her stanzas the voices of those who have been, in the words of Stauffer, abandoned by humanity compounded by the experience of not being heard. Perhaps because of its pithy, if riddling, directness, the opening stanza of the last poem in An Atlas of the Difficult World , Final Notations, willed its way into my memory like a popular song. This shadow sonnet, with its intricate and entangled complexity seemed to have come a far distance from the tidiness of the often-anthologized Aunt Jennifers Tigers, a poem that appeared in her first collection. The open-ended pronoun it seemed as likely to land in change as in poetry or life or childbirth: It will not be simple, it will not be long it will take little time, it will take all your thought it will take all your heart, it will take all your breath it will be short, it will not be simple As readers, when we are lucky, we can experience a poets changes through language over a lifetime. For me, these lines enacted Richs statement in Images for Godard (1970) that the moment of change is the only poem.

Next page

BY ADRIENNE RICH Later Poems: Selected and New, 19712012 Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 20072010 A Human Eye: Essays on Art and Society, 19972008 Poetry & Commitment: An Essay Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth: Poems 20042006 The School Among the Ruins: Poems 20002004 What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems 19502001 Fox: Poems 19982000 Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations Midnight Salvage: Poems 19951998 Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 19911995 Collected Early Poems 19501970 An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 19881991 Times Power: Poems 19851988 Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 19791985 Your Native Land, Your Life: Poems Sources A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far: Poems 19781981 On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 19661978 The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 19741977 Twenty-One Love Poems Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution Poems: Selected and New, 19501974 Diving into the Wreck: Poems 19711972 The Will to Change: Poems 19681970 Leaflets: Poems 19651968 Necessities of Life Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 19541962 The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems A Change of World COLLECTED POEMS 1950-2012

BY ADRIENNE RICH Later Poems: Selected and New, 19712012 Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 20072010 A Human Eye: Essays on Art and Society, 19972008 Poetry & Commitment: An Essay Telephone Ringing in the Labyrinth: Poems 20042006 The School Among the Ruins: Poems 20002004 What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems 19502001 Fox: Poems 19982000 Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations Midnight Salvage: Poems 19951998 Dark Fields of the Republic: Poems 19911995 Collected Early Poems 19501970 An Atlas of the Difficult World: Poems 19881991 Times Power: Poems 19851988 Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose 19791985 Your Native Land, Your Life: Poems Sources A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far: Poems 19781981 On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: Selected Prose, 19661978 The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 19741977 Twenty-One Love Poems Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution Poems: Selected and New, 19501974 Diving into the Wreck: Poems 19711972 The Will to Change: Poems 19681970 Leaflets: Poems 19651968 Necessities of Life Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law: Poems 19541962 The Diamond Cutters and Other Poems A Change of World COLLECTED POEMS 1950-2012  ADRIENNE

ADRIENNE Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. CONTENTS BY CLAUDIA RANKINE In answer to the question Does poetry play a role in social change? Adrienne Rich once answered: Yes, where poetry is liberative language, connecting the fragments within us, connecting us to others like and unlike ourselves, replenishing our desire. [I]n poetry words can say more than they mean and mean more than they say. In a time of frontal assaults both on language and on human solidarity, poetry can remind us of all we are in danger of losingdisturb us, embolden us out of resignation. There are many great poets, but not all of them alter the ways in which we understand the world we live in; not all of them suggest that words can be held responsible.

Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks. CONTENTS BY CLAUDIA RANKINE In answer to the question Does poetry play a role in social change? Adrienne Rich once answered: Yes, where poetry is liberative language, connecting the fragments within us, connecting us to others like and unlike ourselves, replenishing our desire. [I]n poetry words can say more than they mean and mean more than they say. In a time of frontal assaults both on language and on human solidarity, poetry can remind us of all we are in danger of losingdisturb us, embolden us out of resignation. There are many great poets, but not all of them alter the ways in which we understand the world we live in; not all of them suggest that words can be held responsible.