Adjusting type size may change line breaks. Landscape mode may help to preserve line breaks.

Contents

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

William Carlos Williams,

Asphodel, That Greeny Flower

Dead power is everywhere among usin the forest, chopping down the songs; at night in the industrial landscape, wasting and stiffening the new life; in the streets of the city, throwing away the day. We wanted something different for our people: not to find ourselves an old, reactionary republic, full of ghost-fears, the fears of death and the fears of birth. We want something else.

Muriel Rukeyser, The Life of Poetry

... what, anyway,

was that sticky infusion, that rank flavor of blood, that

poetry, by which I lived?

Galway Kinnell, The Bear

Sometimes we drug ourselves with dreams of new ideas. The head will save us. The brain alone will set us free. But there are no new ideas waiting in the wings to save us as women, as human. There are only old and forgotten ones, new combinations, extrapolations and recognitions from within ourselvesalong with the renewed courage to try them out.

Audre Lorde, Poetry Is Not a Luxury

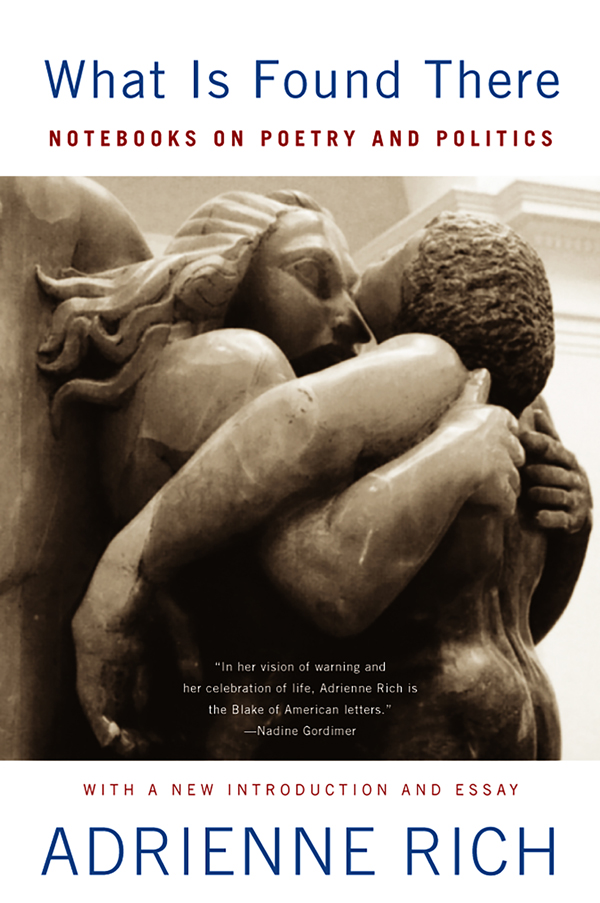

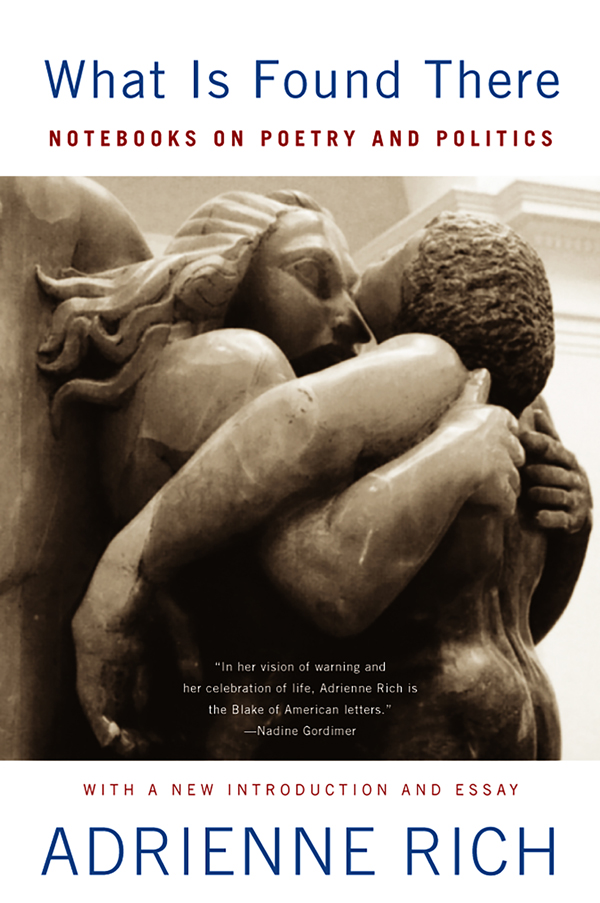

In 2002 in Londons Tate Gallery (the old Tate, where Blake and Turner still dwell) I came upon Jacob Epsteins massive alabaster sculpture of Jacob wrestling with the angel. Both are figures of heavy, gleaming muscularity, found in an embrace that is surely the end of their struggle and as surely erotic in its lineaments. The angels longer hair flows back against its wings, which suggest the tablets of Moses, but are also, as a friend to whom I sent the image on a postcard observed, like barricades. Jacobs hair is short-cropped, tightly curling, and his left arm lies exhaustedly over the right arm of the angel, which is grasping himlifting him off the ground, or holding him up? Each bears weight on one foot, with the opposite knee pressing into the body of the other.

This is the image with which I want to reopen these notebooks, an image befitting the long, erotic, unended wrestling of poetry and politics.

In the biblical story of Jacobs struggle, the person he contends with remains mysterious. He claims to be God, but the tradition prefers him as a messenger. Either way its not just another man. If we follow the story to this extent, the struggle is between human and metahuman, poetry and experience, poetry and material forces. Our angel, then, is not the angel of history, but the messenger from the lived reality of the barricades facing the poet, the individual carrier of poetry. With this messenger poetry has to wrestle every day.

James Scully has observed that

much of what is called political poetry, or poetry that deals with politics, is hackwork. From this comes the generalization that politics destroys poetry. Yet... most of any kind of poetry is hackwork, is slipshod, undemanding of itself.... When you come upon an inept love poem you arent likely to conclude that love and poetry dont mix. You may think the poet is a bad poet, or even a callow person.... But you wont jump to generalizations about the incompatibility of love and poetry.... Assertions that poetry and politics dont mix are not disinterested statements but political interventions in their own right.

He continues:

By rights we should distinguish dissident poetry from protest poetry. Most protest poetry is conceptually shallow. I think of the typical protest anthology: poems in opposition to the Vietnam War or the coup in Chile, ecologically concerned or antinuke poetry (with a few devastating exceptions, mainly Japanese), even poems sympathetic to workers (notably those that focus on workers oppression... ignoring the exploitation that necessitates the oppression). Such poetry is issue-bound, spectatorialrarely the function of an engaged artistic life.... It tends to be reactive, victim-oriented, incapacitated... it seldom speaks the active rage or resolution of... oppressed or exploited people. The real subject is the poets own tender sensibilities.... Dissident poetry, however, does not respect boundaries between private and public, self and other. In breaking the boundaries it breaks silences: speaking for, or at best with , the silenced; opening poetry up, putting it in the middle of life.... It is a poetry that talks back, that would act as part of the world, not simply as a mirror of it.

Scully is one North American poet in whose thinking I see the struggle of Jacob and the angel distinctly wrought. His book of essays, Line Break: Poetry as Social Practice, is one I wish I could put in the hands of every young poet, and many of my contemporaries, for its acuity and passion, gravitas and anger-honed wit. His volume of selected poems (1994) lives up to its title: Raging Beauty .

But the essay closing that volume begins: I no longer write poetry.

Coming from my own location, which is not his, I can profoundly appreciate the sense of futility that produced that statement; a despair about culture as it can serve and veil exploitation. Yet I find there a haste, a swiftness, to dismiss art that does not immediately, recognizably, bring about specific political effectsa giving up on the process whereby language and consciousness can dialectically challenge each other. This is a discomfort with art that has historically haunted the Left as, differently, it has haunted the Right, as it haunted Plato.

To look in a poem for immediate political function is as mistaken as to try to declare immediately what a particular protest demonstration or a picket line has accomplished. Perhaps policies will change, or a better union contract will be achieved. But suppose the particular demonstration does not stop the war, or the picket line only ends in firings and a nonunion shop. Does this render such actions useless? The process of social transformation doesnt fold up into the package of a discrete event. Participation in a demonstration or a picket line can be a form of education. People experience in their own minds and bodies the forms of power, both grass-roots and official. They find and confirm each other out there. The reading or hearing of a poem can transform consciousness, not according to some preordered program but in the disorderly welter of subjectivity and imagination, the seeing and touching of another, of others, through language.

Lus Rodriguez has worked for many years with gang and ex-gang youth, with prisoners and others precariously situated. In his vivid and concretely argued Hearts and Hands: Creating Community in Violent Times, he draws on long experience as a battle-scarred cultural worker and leaves no doubt that poetry, as one readily available form of artistic production, as expressive language, can change young lives through giving words and form to chaos and desperation. Rodriguez is lucid as to the system that creates poverty and youth violence, and knows it must be addressed. But hes equally lucid as to the lives that must be saved along the way.

I too find myself impatient with much that currently represents itself as poetrydissident or not. I want a kind of poetry that doesnt bother either to praise or curse at parties or leaders, even systems, but that reveals how we areinwardly as well as outwardlyunder conditions of great imbalance and abuse of material power. How are our private negotiations and sensibilities swayed and bruised, how do we make lovein the most intimate and in the largest sensehow (in every sense) do we feel? How do we try to make sense ? I want to gesture toward a poetry of ourselves and others under the conditions of twenty-first-century absolutism, making us dimensional in a time when the human concrete is continually erased by state and religious violence and by disingenuous jargon serving state power. Without grappling with the messenger from the barricades, our poems atrophy, get swallowed up into that nexus of euphemism and obliquity obscuring violence.

Next page