Contents

by Dr. John E. Strobeck, MD, PhD

Detox: Is it Extremely Radical or Extremely Rational?

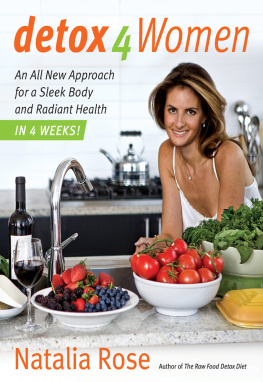

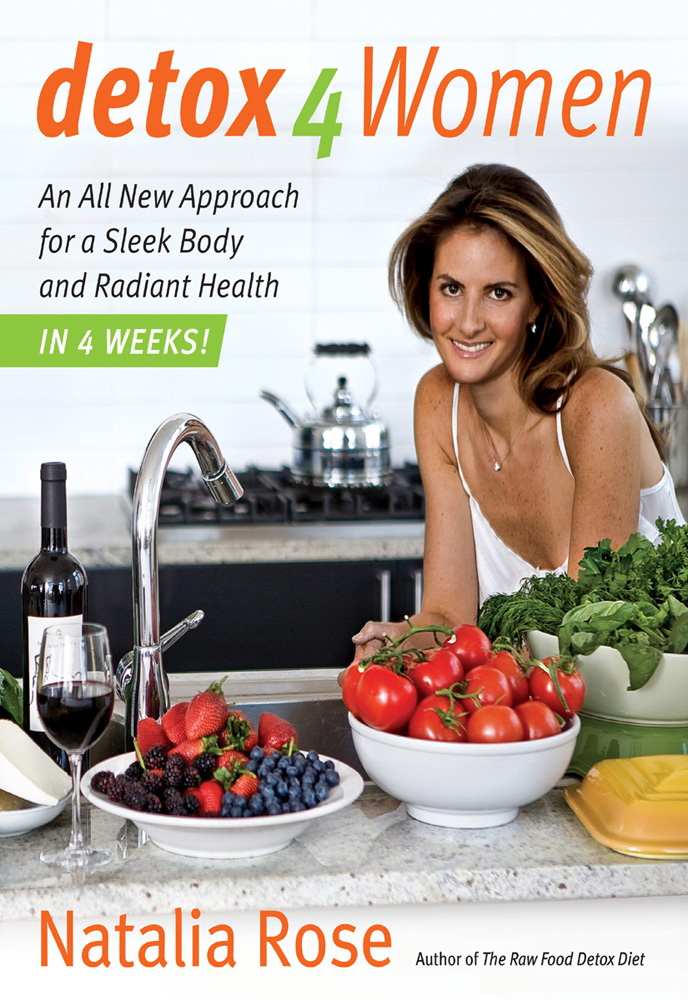

Detox for Women

Sarah Appleton, Fashion Model, NYC

Susie Castillo, Actress, Los Angeles, CA

Three Steps to Detox

Starve the Yeast

Yellow-Light Starches and Sugars

Avoid Foods That Are Hard to Digest

Eat Quick-Exit Meals

Create Space in Your GI (Gastrointestinal) Tract

Grand Finale: the Food Waste Exits

The Only Effective Detox Scenario

Make a Plan

Do It!

Jennifer Gonzalez, 25, New York, NY

The Detox for Women Program

The Recipes

Detox and Exercise

Lisa Rosenbloom, Marathon Runner and Mother of Four, Los Angeles, CA

Kris Carr, Author of Crazy Sexy Cancer Tips and Crazy Sexy Cancer Survivor

Casey Thomas, 26, Sydney, Australia

Kristen Conrad, 23

Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.

HIPPOCRATES

H aving practiced cardiology for the past twenty years, I find it alarming that despite the increased amount of evidence demonstrating the benefits of eating raw and unprocessed food, Americans seem to have lost their nutritional way. They find it very difficult, if not impossible, to change their lifestyle to a healthier one. So I am especially happy to see that in this book, Detox for Women , Natalia Rose, an accomplished author and student of nutrition, has tackled the psychological and physical complexities driving Americas eating habits. She leads us out of the darkness and into the light of a healthy dietary and low-stress lifestyle synonymous with longer life, free of many chronic diseases.

Most of us in the United States and Western Europe were born of parents who were raised in the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. These were times, except perhaps for the periods of the Great Depression and during World War II, when food was plentiful and the growth of the meat, dairy, and tobacco industries was meteoric. Nutrition, based on the inclusion of meat, dairy products, vegetables, and grains, and often described as a food pyramid to follow by governmental agencies, was always portrayed as wholesome and nutritionally complete. Many mornings growing up included a hearty breakfast of eggs, bacon, sausage, or ham, and fried potatoes, washed down with a glass of whole milk. However, to feed the growing demand for the meat, potato, and dairy staples, industry supported plant and animal science to find ways to enhance crop and feed production using new fertilizers and effective pesticides, to make cattle, chicken, and pork farms more efficient and cost-effective, to increase the milk production of individual cows, and to reduce infectious contamination of products after the animals were sacrificed. The thought never occurred to me as I was entering medical school that food, in our society, was so closely related to some of the most dreaded chronic diseases, such as gastrointestinal disease, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

We have been conditioned to believe that living and eating well are birthrights, and we start to follow a lifestyle of excess at an early age. Obesity, a well-defined marker of poor nutrition, was something that happened to poor souls who couldnt control their eating and/or didnt exercise regularly. However, obesity in our society does not affect a minority of citizens, it affects the majority. Obesity in Western society is the direct result of poor nutrition. Poor nutrition (defined as regular consumption of animal meats, dairy products, and processed grains) has been associated epidemiologically with a multitude of chronic diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system, the cardiovascular system, the lungs, the endocrine system, the immune system, the nervous system, the joints, and the skin. Poor nutrition has been directly linked to lethal events such as myocardial infarction, stroke, cancer, respiratory insufficiency, immune deficiency, and accelerated aging. The impact of the addition of tobacco consumption to poor nutrition has long been recognized as a world health problem and continues to grow due to the enabling policies of both government and commercial interests.

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that Western-style diets rich in animal meats, fatty foods, added fats, desserts, and sweets are associated with a substantially increased risk for obesity, type II diabetes, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. Dietary patterns that are characterized by a healthy diet high in fruit, vegetables, whole grains, fish, and small amounts of poultry are associated with a lower risk of these diseases. These associations are stronger for dietary patterns than for individual foods, highlighting the importance of identifying and changing foods that are in excess and adding foods that are too limited in the diet. Lifestyle interventions have been shown to have results comparable or superior to drug therapy. As an example, in the Diabetes Prevention Study, diet and exercise were more effective than metformin in preventing people with impaired glucose tolerance from progressing to diabetes. In addition to improvements to patient health, lifestyle-oriented change can be cost-effective, especially in high-risk groups.

Over the past fifty years the dietary lifestyle that has undergone the most extensive study has been the so-called Mediterranean diet. The Mediterranean diet is a modern nutritional recommendation inspired by the traditional dietary patterns of some of the countries of the Mediterranean Basin. Based on food patterns typical of Crete, much of the rest of Greece, and southern Italy in the early 1960s, this diet, in addition to regular physical activity, emphasizes abundant plant foods, fresh fruit as the typical daily dessert, olive oil as the principal source of fat, minimal dairy products (principally cheese and yogurt), fish and poultry consumed in low to moderate amounts, zero to four eggs consumed weekly, high levels of dietary fiber, red meat consumed in very low amounts, and wine consumed in low to moderate amounts. Total fat in this diet is 25 percent to 35 percent of total calories, with saturated fat at 8 percent or less of total calories.

These reported benefits of the Mediterranean diet represent an apparent paradox: although the people living in Mediterranean countries tend to consume relatively high amounts of fat, they have far lower rates of cardiovascular disease than countries like the United States, where similar levels of total fat consumption are found. One of the obvious differences is the large amount of healthy fat (olive oil, avocado, etc.) used in the Mediterranean diet. The other main differences include the greater proportion of green vegetables, fruits, legumes, and unprocessed grains compared to the average American diet. Unlike the high amount of animal and dairy fats typical to the American diet that raise cholesterol, healthy fats lower cholesterol levels in the blood. The diet also is known to lower blood sugar levels and blood pressure, and recently was demonstrated to prevent the development of diabetes in a large series. A nearly 50 percent reduction in the risk of developing chronic obstructive lung disease and emphysema has also been demonstrated in patients on this diet.