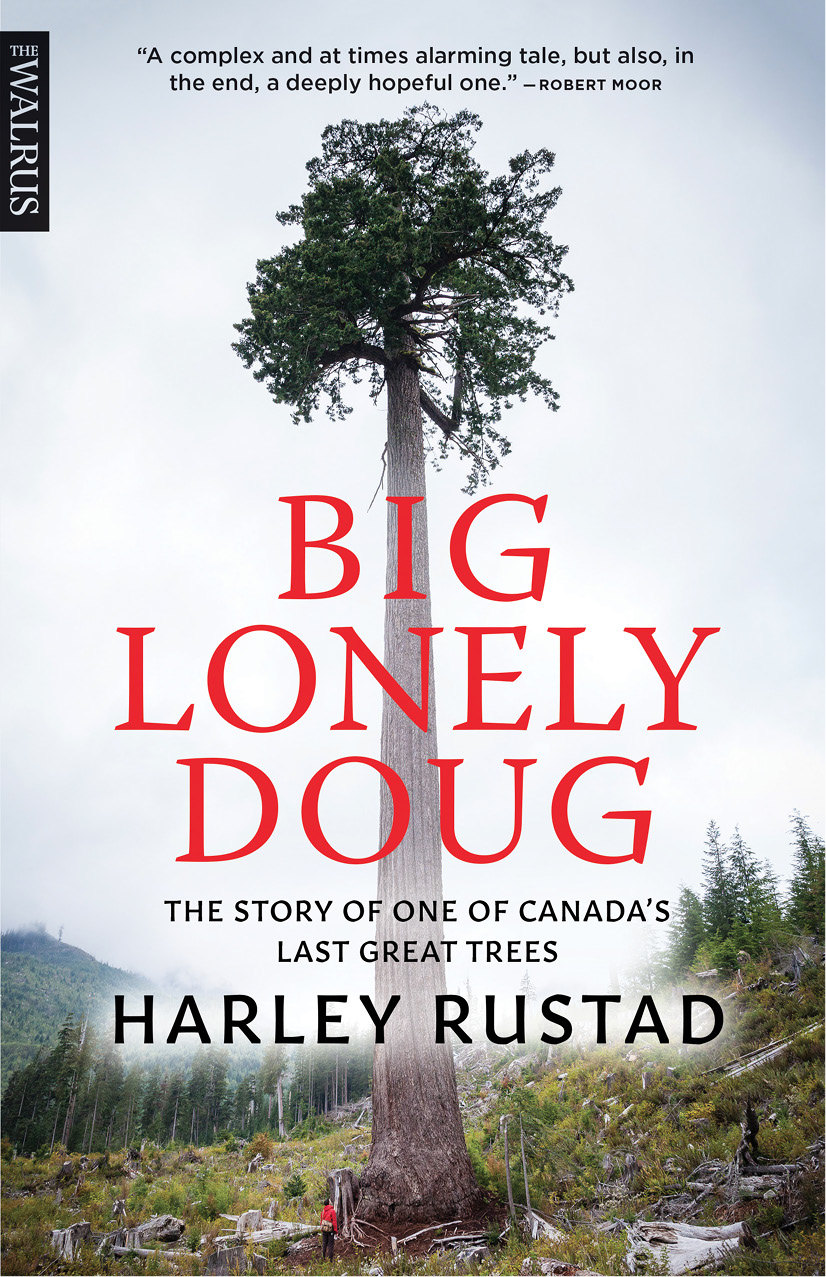

Big Lonely Doug

The Story of One of Canadas Last Great Trees

Harley Rustad

Copyright 2018 Harley Rustad

Published in Canada in 2018 and the USA in 2019 by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the authors rights.Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Rustad, Harley, author

Big Lonely Doug / Harley Rustad.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4870-0311-1 (softcover). ISBN 978-1-4870-0312-8 (EPUB).

ISBN 978-1-4870-0313-5 (Kindle)

1. Old growth forest ecologyBritish Columbia. 2. Old growth

forest conservationBritish Columbia. 3. LoggingBritish Columbia.

4. EcotourismBritish Columbia. I. Title.

QH106.2.B7R87 2018 577.309711 C2018-900673-0

C2018-900674-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018943835

Book design: Alysia Shewchuk

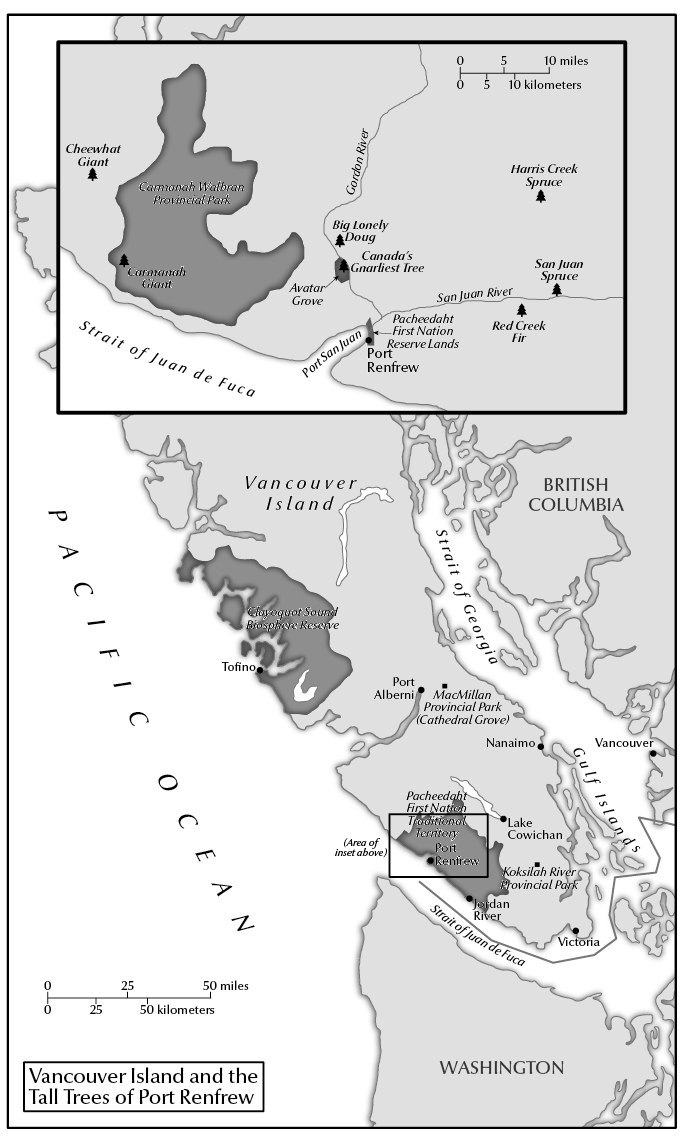

Map of Vancouver Island: Mary Rostad

Cover design: Alysia Shewchuk Cover image: TJ Watt Ancient Forest Alliance

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

For Dad, who taught me how to name the trees

Contents

Prologue

A Seed

A calm wind ruffled the branches of some of the largest trees in the world. It twisted and turned through the forest, picking up scents of cedar and fir and spruce even a faint tinge of salt, this close to the Pacific Ocean. Late afternoon sun had burned off any lingering mist, leaving a clear blue sky.

Nearly every branch on nearly every tree held cones that dangled like ornaments. On one tree, a Douglas fir growing in a valley on Vancouver Island, a cone shook and bounced in the breeze. It began to open. The warm season had caused the cones colour to gradually turn from green and sticky with sap to brown and papery dry, its thumbnail-shaped scales to separate, and the species telltale trident-like bracts to curl the final stage in the cones year-and-a-half cycle to maturation.

As the temperature fluctuated between the early autumns hot days and cool nights, the cone responded accordingly, opening and closing so slightly it would be nearly imperceptible to the eye. One degree of seasonal difference could spell disaster for the precious seeds held within the cone: too hot and they might dry out; too cold and wet and they might rot.

As the sun began to drop behind the forested hills, and when the moisture in the air was just right, a seed dislodged from between the scales and began tumbling earthwards alongside the great trunk of its parent tree. Its feathery tail twirled slightly in the freefall towards a dense undergrowth of salal, sword fern, and huckleberry a fall where the randomness of nature would determine its fate.

The vast majority of the fifty thousand seeds that fell from each tree that year would die. They would be eaten by birds or squirrels or would simply not be lucky enough to find the optimal conditions to sprout. But this one survived. This one landed softly on a patch of moist, green moss growing on the rotting bark of a tree that had been blown over by a fierce wind a century before. Feeding off nutrients in the log, the seed pushed through the moss and into the light. The seedling, barely an inch tall, spread its first pair of glossy green needles.

In time, the seedling would enter an exalted arboreal pantheon, which included some of Canadas biggest trees: western red cedars so wide that it would take ten people holding hands in a chain to encircle their bases; Sitka spruces so tall that their tops would rival towers of a city core; and Douglas firs so old they would outlive more than a dozen human generations. In the wet valleys would grow the epitomes of their respective species great, hulking masses of nature.

These trees would come to attract the attention of loggers, who would put axe and saw to trunk to harvest the warm wood that could be cut and manipulated for innumerable uses. These trees would be surrounded by protestors fighting for their protection, seeing more value in keeping them alive than in their immediate utility. And these trees would attract visitors who wanted little more than to feel awe and wonder in the shadow of one of natures giants.

The seedling grew into a sapling and then it grew into a tree.

Chapter 1

The Ribbon

On a cool morning in the winter of 2011, Dennis Cronin parked his truck by the side of a dirt logging road, laced up his spike-soled caulk boots, put on his red cargo vest and orange hard hat, and stepped into the trees. He had a job to do: walk a stand of old-growth forest and flag it for clear-cutting.

In many ways, this patch of forest was unremarkable. Cronin had spent four decades traipsing through tens of thousands of similar hectares of lush British Columbia rainforest, and had stood under hundreds of giant, ancient trees. Over his career in the logging industry, he had seen the seemingly inexhaustible resource of big timber continue to dwindle, and the unbroken evergreen that once covered Vancouver Island reduced to rare and isolated groves.

Known as cutblock number 7190 by his employer, one of the largest timber companies operating on the island, the twelve hectares represented a small sliver around the size of twelve football fields of the kind of old-growth forest that once spanned the island nearly from tip to tip and coast to coast. But this small patch of trees fringing the left bank of the Gordon River, just north of the small seaside town of Port Renfrew, was a prime example of an endangered ecosystem. Black bears and elk, wolves and cougars passed quietly under its canopy. Red-capped woodpeckers knocked on standing deadwood; squirrels and chipmunks nibbled on cones to extract seeds; and fungi the size of dinner plates protruded from the trunks of some of the largest trees in the world.

Cronin brushed through the salal and fern undergrowth, his jeans wet with dew that even during a hot summer forms every morning in these forests of perpetual damp. Underfoot, mounds of moss covering a thick bed of decaying tree needles were soft and spongy. Sounds dont linger in these forests, arriving and dissipating quickly absorbed by thicket and peat and mist before theyre allowed to swell. For now, the forest was still.

Cronin began the survey along the low edge of cutblock 7190, where he could hear the Gordon River thundering on the other side of a steep gorge. Come spring, salmon fry would be wriggling free of the pebbled river bottom and making their first swim downstream to open water; come fall, mature fish would hurl themselves upstream to spawn. The ancient trees, with their dense tangle of roots growing along the banks of the river, would filter out sediment and loose soil so that even during a rainstorm the forest kept the waters running clear.