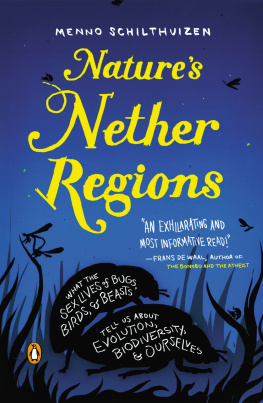

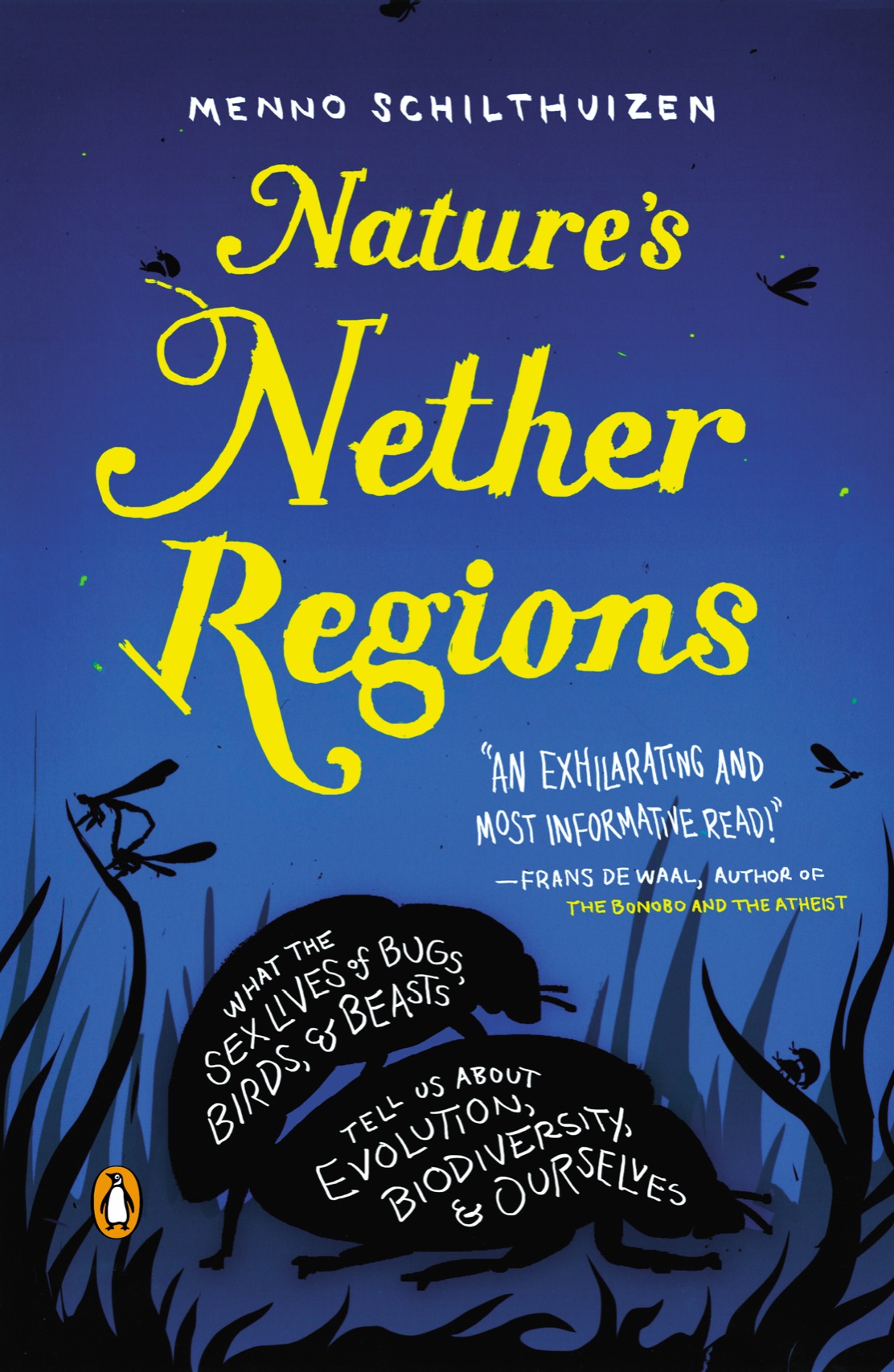

Praise for Menno Schilthuizens Natures Nether Regions

A provocative voyage on the vast ocean of sexual function beyond the quiet backwater that we humans find ourselves in.

Kirkus Reviews

A remarkable book that explores the evolutionary origins of sex organs succeeds in finding exactly the right tone.... Schilthuizens entertaining work reminds us not to take the mechanics of sexual intercourse for granted.

Publishers Weekly

Rather than furiously flipping through a stack of increasingly obscure science journals, those interested now have an easily digestible text to work with, the charmingly titled Natures Nether Regions... interspersed with a selection of the finest, and most scientifically accurate, sex jokes.

VICE Motherboard

Evolutionary biology, it turns out, is a lot kinkier than you might have imagined when you first learned about Darwins theories.... Natures Nether Regions [takes] a closer look between the legs (or, in the case of the Australian velvet worm, on the head) to explore what the sex lives of various creatures can teach us about reproduction, diversity, and human sexuality.

Salon

A sweeping look across the animal kingdom... [that] illustrate[s] an amazing diversity of genitalia that has been largely unappreciated, even among scientists.

LiveScience

What distinguishes this parade of marvels from other wow, is nature weird volumes is that Schilthuizen uses the creatures to offer an appealing introduction to the big themes in current research on how sexual parts, practices, and ornaments have become so elaborate and diverse across the domains of life.

Science News

Schilthuizen whizzes between geographies and species, learning from apes, slugs, spiders. In the process he invites us on all kinds of interesting adventures, from finding ancient beetle genitals trapped in amber to examining barnacles depositing their sperm with eight-foot-long appendages.... This is a book about heterosexual sex between animals, but Schilthuizen hasnt closed the case on other kinds of sex driving animal evolution, too. Ever excited, ever open-minded, he pushes towards new frontiers.

Tess Taylor, Barnes & Noble Review

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Menno Schilthuizen is a Dutch evolutionary biologist, ecologist, and permanent research scientist at Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden and a professor of character evolution and biodiversity at Leiden University, in the Netherlands. From 2000 to 2006 he worked at the Institute for Tropical Biology and Conservation in Sabah, Malaysian-Borneo, where he studied land snail evolution in tropical forests, caves, and limestone habitats. He is the author of Frogs, Flies, and Dandelions: The Making of Species and The Loom of Life: Unraveling Ecosystems. When he is not extracting beetle genitals, he enjoys painting and hiking in the dunes near his hometown, Leiden, the Netherlands.

ALSO BY MENNO SCHILTHUIZEN

Frogs, Flies, and Dandelions: The Making of Species

The Loom of Life: Unravelling Ecosystems

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

First published in the United States of America by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Published in Penguin Books 2015

Copyright 2014 by Menno Schilthuizen Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Illustrations by Jaap Vermeulen. Copyright 2014 by Menno Schilthuizen.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Schilthuizen, Menno.

Natures nether regions : what the sex lives of bugs, birds, and beasts tell us about evolution, biodiversity, and ourselves / Menno Schilthuizen.

pages cm

eISBN 978-1-101-60810-4

1. Generative organsEvolution. 2. Sexual behavior in animalsEvolution. I. Title.

QL876.S35 2014

573.6dc23

2013047833

Cover design: John-Patrick Thomas

Cover lettering: Matt Vee and John-Patrick Thomas

Version_2

... yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.

James Joyce, Ulysses

Preliminaries

Not too long ago, the Netherlands Natural History Museum was housed in a lofty, cavernous building in the historical center of Leiden. Generations of biology students took their zoology classes there, in its two-tier lecture theater over the monumental staircase. During the less captivating parts on crustacean leg structure or mollusk shell dentition, their gaze would have wandered off to the two features that made this lecture room unforgettable. First, its abundant display of antlers of deer, antelope, and other hoofed animals, hundreds of them, suspended from the walls. Second, the huge painting from 1606 of a beached sperm whale that hung over the lectern. On an otherwise nondescript Dutch beach lies the Leviathan, its beak agape, its limp tongue touching the sand. A smattering of well-dressed seventeenth-century Dutchmen stand around the beast. Prominently located, and closest to the dead whale, stand a gentleman and his lady. With a lewd smile, face turned toward his companion, the gentleman points at the two-meter-long penis of the whale that sticks out obscenely from the corpse. Centuries of smoke-tanned varnish cannot conceal the look of bewilderment in her eyes.

These few square feet of canvas, strategically placed in the paintings golden ratio, exemplify two things. First, the unassailable fact (supported by millennia of bathroom graffiti, centuries of suggestive postcards, and decades of Internet images) that humans find genitals endlessly fascinating. Their own, but by extension those of other creatures, too. The amazing diversity in shape, size, and function of the reproductive organs of animals has been an eternal source of wonder, making bestsellers of the 1953 book The Sex Life of Wild Animals, the 1980s classroom wall poster Penises of the Animal Kingdom (over twenty thousand copies sold), and the Sundance Channel series Green Pornoshort films starring a sanguine Isabella Rossellini enacting the copulation of various animals.

The second point that may be underscored with this seventeenth-century sperm whale penis is the curious observation that the public fascination with genitalia was, until very recently at least, not matched by equally intensive scientific inquiry. The lofty offices down the corridor from this lecture theater housed scores of biologists quietly cataloging the worlds biodiversity. In good classificatory tradition, they would painstakingly draw, measure, photograph, and describe the minutiae of the genitals and distinguishing features of the reproductive organs of any new insect, spider, or millipede they would discoverand yet never stop to wonder how these private parts evolved.

We really have Darwin to blame for this. In his next-greatest book, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Darwin explains how secondary sexual characteristicslike colorful bird plumage, the prongs on beetles heads, and the antlers of deerhave been shaped not by natural selection (adaptation to the environment) but by sexual selection: adaptation to the preferences of the other sex. He denies the primary sexual characteristics entry to his theory by categorically stating that sexual selection is not concerned with the genitalia or primary sexual organswhich, after all, are merely functional, not fanciful. So the diversity of all those antlers on the walls of the museum lecture room had been a tradition of evolutionary biology since Darwin, but investigating the evolution of the business end of thingsof which the centerpiece of that seventeenth-century painting is just one prominent examplehadnt.

Next page