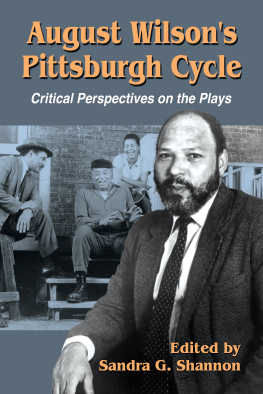

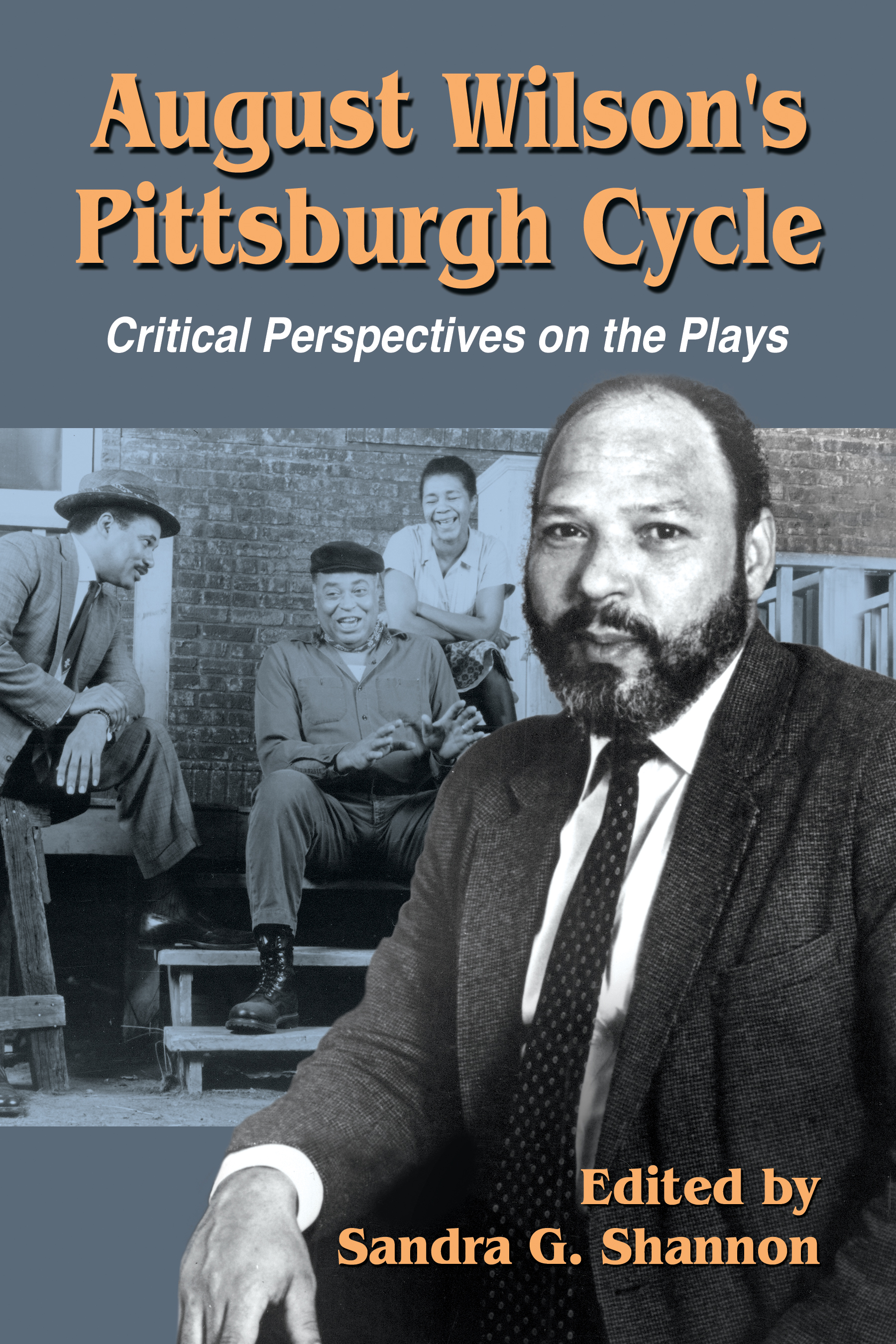

August Wilsons Pittsburgh Cycle

Critical Perspectives on the Plays

Edited by

Sandra G. Shannon

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2299-6

2016 Sandra G. Shannon. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover images: Playwright August Wilson, 1987; Fences performance, with Charles Brown, James Earl Jones and Mary Alice (Stage, 46th St. Theatre, New York, 1987-88) Photofest

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

The work that went into editing August Wilsons Pittsburgh Cycleor any volume of essaysis much like an intricate dance whose mastery not only involves keeping all participants in step but also requires multiple unseen maneuvers on the part of the editor to make the finished product appear as graceful and as seamless as possible. With each new and equally demanding ensemble that I choreograph as either editor or co-editor comes an even greater appreciation for the synchronized efforts of each individual member. In essence, then, I owe a debt of gratitude to the individual authors whose names are listed on the Table of Contents that follows. I acknowledge them here for accepting my initial invitation to be a part of this collection and for seeing this dance to fruition.

Introduction

I believe in the American theatre. I believe in its power to inform about the human condition, I believe in its power to heal, to hold the mirror as twere up to nature, to the truths we uncover, the truths we wrestle from uncertain and sometimes unyielding realities. All of art is a search for ways of being, of living life more fully.

August Wilson, The Ground on Which I Stand, 1996

For August Wilson, writing plays was an intensely personal affair. While it afforded him the means by which to celebrate the unique particulars of black life, this medium also offered him a road map for negotiating the tricky contours of his own life. Beyond the lingering and well documented influences of a distant white father, a stalwart black mother, a motley mix of paternal surrogates, and a passionate black cultural nationalist agenda, August Wilson was driven by a lesser known deep-rooted existential quest to get at the truth of his own existence. Toward this end, his playwriting became a way for him to make sense of the world around him and to determine his place within it in the face of uncertain and sometimes unyielding realities (The Ground 46).

At some indistinguishable point on his way toward maturing and becoming a serious playwright, Wilson felt compelled to distance himselfboth emotionally and culturallyfrom his German immigrant father. Yet while he relegated Frederick Kittel to the background of his life, he filled that void by becoming even more impassioned about the cultural and racial heritage of his African American mother and his maternal grandmothera woman who reportedly trekked from North Carolina to Pennsylvania to trade backbreaking labor in the tobacco fields for a better life in Pittsburghs thriving steel mill industry. This decision to identify with his African American mother and grandmothers cultural heritage apparently moved young Wilsonblessed early on with a poets sensibilityto discover a symbolic correlation between their examples of endurance and racial pride and his incessant quest for the truth of his being.

Emboldened by this connection, Wilson began to understand that his own existentialist yearnings were also part of a larger odyssey for all Africans in America; that is, in coming to terms with his blacknessespecially as he bore the imprint of both African and European racial and cultural tiesWilson would soon realize that the narrative of his singular life ran parallel to that of the black masses in America. The results of this major epiphany moved him to create art out of the depths of his own uneasy experience, negotiating and translating the world from his precarious position as an African in America and, more specifically, from his perspective as a black male. More than once he likened this constant state of negotiation to wrestling with demons. In one of his most cited observations about his playwriting process that can be traced to a 1988 interview with journalist Bill Moyers, he notes,

You discover that youre walking down this landscape of the self, and you have to be willing to confront whatever it is that you discover there. The idea is to emerge at the end of the landscape with something larger than what you had when you went insomething that is part of the illumination of truth. If youre willing to wrestle with your demons, you will find that your spirit gets larger. And when your spirit gets larger, your demons get smaller. For me, this is the process of art. The process of writing the plays is a very liberating thing [178].

For August Wilson, completing his ten-play century cycle, which he likened to his 400-year-old autobiography (Palmer 47), was tantamount to constructing his own private landscape where he not only wrestled with the demons that plagued his life, but also channeled the hardships of African American people. Reminiscent of psychologist and theorist Carl Jungs archetype of the wounded healer, Wilson sought to heal himself while prescribing remedies in the form of plays to treat what he believed ailed his people.

From Wilsons active imagination came a succession of characters fashioned in his own likeness and tortured by similar demons that so menaced their creator. While his portrayal of tragic figures such as Herald Loomis in Joe Turners Comeand Gone, Levee in Ma Raineys Black Bottom, Troy in Fences, and King in King Hedley II strike universal chords of familiarity, in some measure each is faced with the same demons that plagued him. Study carefully any of these social outcasts and misunderstood case studies at the center of these plays to find clues into the playwrights own conflicted universe. Uprooted, restless, tormented, and driven, characters such as Citizen Barlow, Herald Loomis, Levee, Troy Maxson, King Hedley II, and Harmond Wilks go to great lengths to settle a score, right a wrong, get what is their due, or come to terms with self. Also portrayed in several of Wilsons best known plays are enigmatic, shaman-like characters who mirror Wilson in the emotional baggage that they carry that frequently manifests in the form of physical or emotional scars that bespeak of unspeakable pasts. The earth mother and community healer Aunt Ester Tyler (Gem of the Ocean), the voodoo wise man Bynum Walker (Joe Turners Come and Gone) and the cutter waitress Risa (Two Trains Running), for example, possess the dual propensity to uncover and wrestle with their personal truths so that others may not suffer a similar fate.

Much of Wilsons work in the role of artist turned cultural healer was in teaching and arguing the rightful place of Africa at the core of African American identity. As he attempted to cope with an estranged father, choose between warring cultural allegiances, and formulate an Africanist aesthetic, he faced a state of constant psychological turmoil. Author and critic Paul Carter Harrison explains what might stoke this type of tempestuous inner battle in Wilson in a seminal essay entitled August Wilsons Blues Poetics. Here, Harrison asserts that marginalization prompted African Americans to probe the recesses of ancestral memory for recognizable African values, linguistic techniques, and aesthetic constructions that could be cultivated as a source of ethnic reaffirmation (292). Harrison further argues that the revival of a collective, African memory had a chastening effect on contemporary black artists, urging them away from a posture of cultural ambivalence to achieve a vigorous, uncompromised expression of ethnic ethos in the creative process (298). Africa, then, became the refuge for Wilson as it did for many artists having to contend with still relevant tensions caused by what Langston Hughes referred to as the racial mountain.

Next page