To Joe Henderson and Rich Koster, who encouraged when encouragement was needed, praised when praise was due, and were silent when that was the kindest thing to do.

Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author, or the publisher.

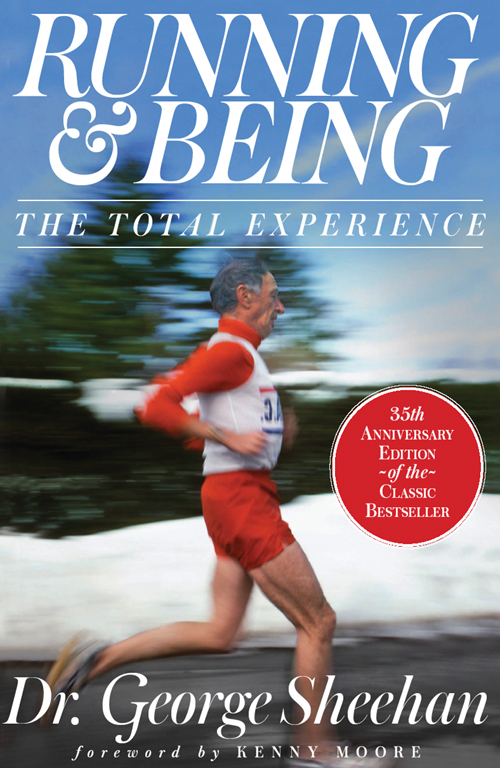

1978 by The George Sheehan Trust

Foreword 2013 by Andrew Sheehan

Introduction 2013 by Kenny Moore

Trade hardcover published by Rodale Inc. in April 2013 in agreement with The George Sheehan Trust.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

Illustrations by Monica Sheehan

Book design by Christina Gaugler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

ISBN 9781609619305 hardcover

eISBN 9781609619312

We inspire and enable people to improve their lives and the world around them.

rodalebooks.com

ALSO BY GEORGE SHEEHAN, MD

Dr. Sheehan on Running (1975)

Medical Advice for Runners (1978)

This Running Life (1980)

How to Feel Great 24 Hours a Day (1983)

(published in paperback as Dr. Sheehan on Fitness)

Personal Best (1989)

Running to Win (1991)

Going the Distance (1995)

contents

Running

foreword

C all it a blessing or a curse, but you can never escape the voice of a parent. The same voice that called you off the playground as a kid will echo in your head years after hes goneadvising, admonishing, encouraging. Though he passed nearly two decades ago, our dads voice continues to find we Sheehans, his sons and daughters.

Sometimes its the voice of an adult exhorting the need for challenge. If you dont have a challenge, find one, Dad would say. Other times, its someone much younger telling us to lighten up and remember how to play. And since we are runners ourselves, its not surprising that his is the inner voice that compels us onward. We are not alone.

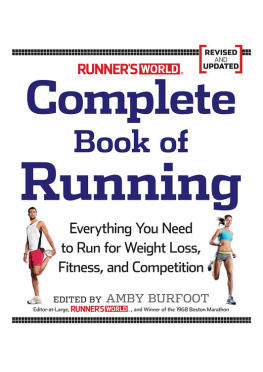

With the publication of Running & Being in 1978, George Sheehans voice became the voice of a movement, sounding a clarion call to hundreds of thousands of people to abandon their sedentary ways, take to the streets, and run. Today, there are millions of us lacing up our running shoes, training for 5-Ks, 10-Ks, half-marathons, and marathonseach trudging the same path of fitness and self-discovery that he blazed decades before.

None of us saw this coming. As a respected physician and the head of our large family, our dad seemed much like the other dads we knew in our small town on the Jersey shore. Like most of his generation, he hung up his track spikes after college, devoting his energies to his patients and growing family, his athletic activity reduced to that of a spectator and the occasional squash or tennis game. As we took up sports, he showed up at our games and meets to cheer us on. But watching his kids compete rekindled his athletic spirit. He felt something was missing. At 45, 2 years after the birth of his last child, he started running again.

He began with a simple goal: to run a 5-minute mile. He ran a loop in our backyard before venturing on to the roads. In 1963, the novelty of a middle-age man running the streets in his underwear was met with disbelief and derision. That didnt faze him. He found similar pilgrims in the then-small community of road runners who offered a return to competitive racing and dreams of the Boston Marathon. A year later, he completed the first of what would be 21 consecutive Bostons and more than 60 marathons overall. Aging is a myth, he argued, and he showed it by posting his personal best at 3:01 in his 61st year. And that sub-5-minute mile? He became the first 50-year-old to do it, running 4:47 in 1969.

Along the way, he made a deal with the sports editor of the local paper to cover the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and then to pen a weekly column. A tireless correspondent, he would sit in our TV room with a yellow legal pad in hand, scribbling responses to the swelling stream of letters he received from fellow runners. In 1970, he became medical editor of Runners World and wrote his first column for the magazine. Two years later, his first bookon sports medicineappeared. As his audience grew, his writing focused less on the treatment of athletic injuries and more on his and his readers athletic experience and how it changed their lives. The burgeoning running movementa movement with movement he called itpropelled Running & Being to the top of the New York Times bestseller list following Jim Fixxs The Complete Book of Running. More books followed, seven in all, culminating in Going the Distance, his account of his duel with the cancer that ultimately led to his death in 1993.

There were other forerunners who must be recognized as well. Bill Bowerman, Kenneth Cooper, and Fred Lebow to name a few. Women pioneers like Grete Waitz and Joan Benoit Samuelson. But what our father brought to the party was the party itself. In a word: play. While others espoused the practical health benefits of running, he trumpeted the impractical, knowing that running would be just another passing fad if people did it just because it was good for them. Newcomers would drop the sport in a month if they ran out of duty. They would embrace it for a lifetime if running became their play.

Play is where life lives. Where the game is a game, Dad wrote. At its border, we slip into heresy. Become serious. Lose our sense of humor.... Money, power, position become ends. The game becomes winning. And we lose the good life and the good things that play provides. To him, work was mandatory, but play was essential. Todays work does not make us the persons we can be. Work is simply the price to be paid. Having earned our daily bread, we can turn to our daily play.

Through the play of his hour-long runs, he became unbound and unburdened. Like Henry David Thoreau in his walks at Walden Pond, Dad found that running could help simplify his life, stripping from it the complicating need for possessions and position. The sky, the air, and the trail by the river were all free to enjoy, and to experience them all through running was liberating for him. Even more important, play became the gateway to self-discovery. In running, he got closer and closer to becoming the person he was meant to benot someone elses idea of who he should be. He urged his readers to find and celebrate their authentic selves and to take back control over their lives. In his words: to possess ones own experience rather than be possessed by it, to live ones own life rather than be lived by itin time, to become all you are.

It was in this spirit that the running-fitness revolution was christened. They were heady days with all manner of folks out there running for the first time, unsure at the start just where they were going. As much as anyone, George Sheehan led the way. Unshackled from convention, he had embraced his own eccentricities and encouraged those who read his articles and attended his prerace talks to embrace their own. Runners got the message. Road races and marathons sprung up all around the country. Starting lines swelled into festivals. The party had begun.