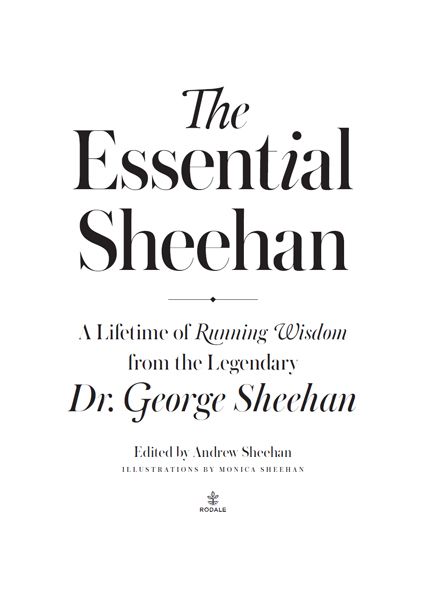

ALSO BY DR.GEORGE SHEEHAN

Dr. Sheehan on Running (1975)

Running & Being (1978, 1998, 2013)

Medical Advice for Runners (1978)

This Running Life (1980)

How to Feel Great 24 Hours a Day (1983)

(Published in paperback as Dr. Sheehan on Fitness)

Personal Best (1989)

Running to Win (1991)

Going the Distance (1995)

Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author, or the publisher.

2013 by The George Sheehan Trust

Portions of this work have been previously published in Runners World magazine, as well as Dr. Sheehan on Running (1975), Running & Being (1978, 1998, 2013), This Running Life (1980), How to Feel Great 24 Hours a Day (1983) (published in paperback as Dr. Sheehan on Fitness), Personal Best (1989), Running to Win (1991), Going the Distance (1995).

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

Runners World is a registered trademark of Rodale Inc.

Book design by Nora Sheehan

Illustrations by Monica Sheehan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher

ISBN-13: 978-1-60961-932-9 hardcover

eISBN-13: 978-1-60961-933-6

We inspire and enable people to improve their lives and the world around them.

rodalebooks.com

To Mary Jane and our sons and daughters, who waited with patience and love while I sought the lightand finally found my way home.

DR. GEORGE SHEEHAN

Contents

Foreword by David Willey,

editor-in-chief of Runners World

Foreword

BY DAVID WILLEY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF RUNNERS WORLD

O NE OF THE FIRST things I did when I became the editor-in-chief of Runners World in 2003 was to hang a framed photo of Dr. George Sheehan on the wall of my office. George, who began writing a column for the magazine in 1970, was the magazines most popular and beloved writer before his death from prostate cancer in 1993. He wrote about running not only as a sport but as a method for living a fuller life. This approach helped land several of his books on the bestseller list, and anytime I look at one of those lists today or browse the self-help shelves at a bookstore, I think of him. George was writing self-help books before there was such a category; one can easily imagine his 1983 book, How to Feel Great 24 Hours a Day, being published today and successfully marketed to millions of readers yearning to live healthier, happier, better lives.

But calling George Sheehan a writer is like calling Muhammad Ali a boxer. Its true but incomplete. He was a popular speaker who filled auditoriums at races, sports-medicine conferences, and corporate retreats. He was called a guru and a philosopher-poet, and he regularly quoted classical writers such as Ortega, Tiberius, and William James, which naturally led some to accuse him of being obsessive and overwrought. But it is inarguable that he was a visionary and a pioneer who deserves credit for helping to launch Americas first running boom. No one has ever done more to explain, simply, eloquently and honestly, the how and the why of living a running life. At his best, George connected running to something larger than putting one foot in front of the other.

I dont remember exactly where I found that photo, but it was with stack of race posters from decades past, forgotten. In the photo, George is sitting in a wooden rocking chair on the deck of his house in Ocean Grove, New Jersey, overlooking the Sound. Hes dressed in running clothes, and a towel is draped over the back of his chair, but its unclear whether he has just returned from a run or is about to set out. What is clear is that George is writingor, more specifically, hunting and pecking away at what looks to be an old Royal typewriter perched on his decks wall, seemingly a few inches from falling into the drink. There isnt a shred of artifice or self-consciousness to be found anywhere. The photo is still on my wall today (and on this books cover), even though we moved into a new building several years ago. Beneath it is my own Royal typewriter. The symbolism isnt subtle: There are things from the pasteven forgotten, old-school thingsthat still matter today.

As a longtime Runners World subscriber and the son of a Runners World reader in the 1970s and 80s, I had read Georges column religiously. I should say columns, plural, because his contributions to the magazine appeared under a range of titles that reflected his growing popularity and the magazines broadening readership, which grew to embrace beginning runners as well as the highly dedicated (and mostly male) crew that ran nearly every day and cared immensely about races and PRs. First there was a simple column called Medical Advice. George was a medical doctor by training, after alla cardiologistwith plenty of advice for runners eager to treat and avoid common injuries. That morphed into Dr. Sheehan on Running (also the title of one of his books), in which he spread his wings a bit more, followed by the insider-y From Sheehan and the slightly more forthcoming From George Sheehan. Until his death, he wrote under George Sheehans Viewpoint, which sounds drier than it was, I assure you. Runners often say that running helped them find themselves. For many of them, George held a lantern. In a 1988 profile of George for Runners World, John Brant put it perfectly, describing his first encounters with the proselytizing distance runner at a newsstand during some luckless post-college years: During the few minutes it took to read the column you forgot about your confusions and footlessness. When you were finished you put the magazine back on the rack. You rubbed your hands up and down the legs of your jeans. Then you broke out of the store and back to your rented room. You changed as fast as you could and took off running. You were no longer lost. Sheehan had reminded you that your life was pinned to something. He had granted you solace and permission.

In my first few months as editor-in-chief, I immersed myself in these columns again. Sure enough, they made me want to run and push myself to be better. More important, now that I was a bit older and married and had a family and priorities larger than my own health and fitness, they reminded me to continually try to live a heroic life. George strongly believed that all of us are here to do exactly that. Our highest human need is to be a hero, he wrote. When we cease to be heroic, we no longer truly exist. That may sound a bit over the top to some, but George saw heroism as being within anyones grasp, writing that through ordinary experiences, the ordinary person can become extraordinary.

Its key to understand how George framed heroism: with a lowercase h, not focused on public glory or on vanquishing opponents. Our only real rivals, he believed, are our youthful selves, and our most urgent struggles are against inertia and indifference. They need to be met every day, but it doesnt matter if no one else is aware of this strugglethe hero needs no recognition. The deed is done, and the audience of one is satisfied. Can an early-morning run or 25 miles per week really carry such significance? Yes.

Next page