Contents

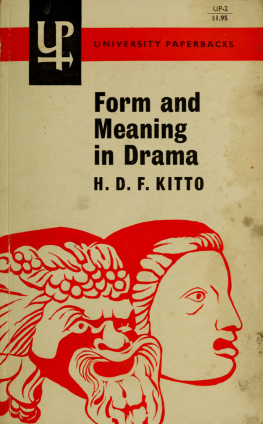

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS:

RENAISSANCE DRAMA

Volume 14

SHAKESPEARES TRAGIC JUSTICE

SHAKESPEARES TRAGIC JUSTICE

C. J. SISSON

First published in 1963 by Methuen & Co Ltd

This edition first published in 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1963 C. J. Sisson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-138-71372-7 (Set)

ISBN: 978-1-315-19807-1 (Set) (ebk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-23462-8 (Volume 14) (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-23465-9 (Volume 14) (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-30639-1 (Volume 14) (ebk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

SHAKESPEARES

TRAGIC

JUSTICE

by

C.J. SISSON

METHUEN & CO LTD

36 ESSEX STREET, LONDON WC2

2/2549/10

All rights reserved Printed and bound in Canada by W. J. Gage Limited

Designed by Arnold Rockman MTDC

CONTENTS

I

Public justice: Macbeth

II

Private justice: Othello

III

The dilemma: Hamlet

IV

The quandary: King Lear

PREFACE

Justice is an intensely alive problem in the world of today, affecting alike the individual in the conduct of his own life, the State in its organisation of society and its administration of the law, and the inter-relations of States and communities. It was a matter of no less deep concern to Elizabethan England.

Attempts have been made of late to increase Shakespeares stature, or perhaps to make him more palatable to contemporary taste, by reading into his plays significances of moment mainly or exclusively for our own day, even in the form of concepts that were literally unthinkable to Shakespeare and his day, such as the notorious Oedipus Complex as the basic theme of Hamlet. It is not thus that Shakespeare is vindicated as for all time. In his plays he reflects his own thought, and the life and thought of his own time, and in so doing presents dramatic pictures of problems of life that are significant to all ages of mankind. By virtue of his deep humanity and creative imaginativeness Shakespeare is both of an age and for all time.

The problem of justice, human and divine, seems to have haunted Shakespeare, as it haunted Renaissance Christendom, and as it emerges most plainly in his greatest tragedies. Of these four studies of justice in action, that of King Lear may well appear, if understood aright, to have gone far beyond the most advanced present-day thought on this most poignant problem of life and society. Here indeed it is not for us to seek to bring Shakespeare level with us today, but to raise ourselves to his level.

It is generally held that Shakespeares last plays reflect a turning in his later years to a more benign observation of life and character, in which a warm optimism colours his representation of human nature. Some shall be pardoned and some punished is the judgment of the Prince at the end of Romeo and Juliet, an early tragedy. But Pardons the word to all in Cymbeline, freeing even Iachimo, the plotter of evil, whose penitence is sharply contrasted with the obduracy of Iago in Othello. Justice, it might seem, is increasingly superseded by mercy in the dramatic world over which Shakespeare ruled.

Comedy, of course, has a logic of its own that differs from the logic of tragedy, and Shakespeares latest plays are comedies, though Cymbeline happens to be included among the Tragedies in the First Folio. It is noticeable that the most powerful and moving appeals to mercy occur in an early comedy, The Merchant of Venice, and in a late comedy, Measure for Measure. And it is perhaps significant that in each instance the appeal comes from a woman, from Portia and from Isabella. Isabellas plea, indeed, interprets for us the deep-laid foundations of Elizabethan thought upon justice and mercy. Mercy must temper justice in human society if the world of men is to resemble the spiritual world of which it seeks to be the faint and imperfect image. Under the justice of God all men stand condemned for sin, and their sole hope lies in His mercy, which is infinite. Shakespeare was born and lived in an atmosphere of thought in which human justice reflected this conception of divine justice. His father and his father-in-law alike, in offending against the laws of the manors of which they were tenants, had come to stand, in the immemorial phrase, in the mercy of the Lord of a Manor. The prerogative of mercy lay in the powers of a King, the fountain of justice, Gods representative on earth, and from him the laws ultimately derived, though he delegated their administration.

Under the Tudors, however, that delegation was far from complete in the great Prerogative Courts, which were closely linked up with the Kings Privy Council. In these courts the reserved power of the fountain of justice made itself felt against the operation of common law and statute law, and they were of all-pervading significance in Shakespeares England as Courts of Appeal against the Common Law Courts. The Court of Requests, a poor mans court, wrote Sir Francis Walsingham in 1583, is appointed to mitigate the rigour of proceeding at law. Portias appeal to Shylock for mercy and reconciliation would seem familiar ground to the judges in the Court of Chancery. It was their aim to bring opposing parties to agreement rather than to judgment, and even when judgment was given, and before a final decree was passed, to plead with the successful party to show mercy and pity, as we may read the records extant of their decrees and orders.

When Shakespeare died, a little more than midway through the reign of King James, a marked change was coming over the atmosphere of thought concerning justice. It is familiar in the views of the famous John Selden, a great Common Lawyer and historian of the law. For him the true basis of the law, as of the monarchy, is a social contract. A King is a thing men have made for their own sakes, for quietness sake. uncertain and changeable. In such a view, justice descends to earth and renounces all divine sanction and exemplar for human society. Whatever the rights of this conflict in juristic theoryand it was one of the fundamental causes of the Civil Warit is clear that the older traditional conception was more fitted to the purposes of the drama and to the exposition of problems of justice in human life, linking them up with the infinities of moral and spiritual law, and presenting their arbiter as a Duke, a Prince, or a King.