How dull it is to pause to make an end.

T his book would not have happened without the support of many people: that thought makes me reflect about what a lucky man I have actually been so far in my life. Without a word of complaint, Sandra puts up with my unaffiliated, lone-wolf writerdom, while I puzzle these things out and tap them slowly into Word. Before I began writing today, there, on the floor of our walk-in closet, I found my wedding ring, which had been lost for ten days. I was incomplete without it in a way that all women and some men will understand. Thirty-two years and three sons later, I am still, in Sandra's eyes, the stormy young poet she met in Los Angeles in our twenties. There is no greater gift than the personal freedom that flows from her acceptance of me. How wisely my spirit chose her. I have not always been so wise.

In these books, I am trying to work backward to discover what caused the explosions in population, as well as the economic and technological growth that shaped our modern world and caused us to ignore or devalue the most fundamental human satisfactions. I believe that when I consult the record and start over at the beginning, many obscure things become clear. Conversations with Leonard Lopate (WNYC), Donna Seaman (Open Books), and Terry Milewski (CBC) challenged me and made me realize that Made to Break had left the job unfinished. I am grateful to have such skilled readers, and I am grateful for the attention that Made to Break garnered. This was a direct result of the effort devoted to the book by Michael Fisher, Susan Boehmer, and RoseAnn Miller of Harvard University Press, all of whom I have never met in person or thanked adequately.

Lew Daly (of Demos in Manhattan) introduced me to his agent, Andrew Stuart, who sold this book for me with great patience and great faith. The conversations, exchanges, and ideas I've gleaned from Tom Bentley-Harapnuik, Lester R. Brown, Chris Bucci, Michael Bugeja, Joe Cacioppo, Nicholas Christakis, Cari Copeman-Haynes, Robert Copeman-Haynes, Richard Crawford, Cosima Dannoritzer, Alain de Botton, Ellen Dissanayake, Brian Dolan, Sonni Efron, Dean Falk, Stanley Fish, Adam Garfinkle, Anthony Giddens, Clive Hamilton, Paul Headrick, Christopher Hitchens, Mark Katz, Tsukao Toby Kawahigashi, Ned Kock, Elizabeth Kolbert, Serge Latouche, Cameron MacPhee, Bill McKibben, Andrew Nikiforuk, David Nye, Henry Petroski, Murray Phillips, David Pogue, Laura Pappano, Elizabeth Royte, Matt Richtel, Eric Rumble, Liz Sherman (of Joyride!), Mandy Sigurgeirson, Susan Strasser, Gus Speth, David Suzuki, Sherry Turkle, John Vaillant, Fred Weil, and Chris Wood shaped my thoughts or jolted me to react. I deeply regret not being able to speak with Steve Jobs, who died before we could meet. In my mind, he is a figure like Thomas Edison or Henry Ford. I wanted to talk to him as much as I still want to speak with Bill Gates, who I hope will read this and agree before I sit down to write the third book in what I have come to think of as The Potlatch Trilogy, a trio of books exploring the emergent consciousness of consumer society. How bout it, Bill? At the very least, it would be an interesting chat.

I would also like to thank the people at Prometheus Books for their forbearance. Linda Greenspan Regan acquired this title and began steering it toward completion before retiring. I am in her debt. In her stead, Steven L. Mitchell deserves considerable thanks for patiently and wisely giving me enough time to complete the research into the dozen different fields that contribute to the document you are now reading. Cate Roberts-Abel kept us all on track as we tried to meet the tight deadlines that resulted from protracted drafts. Melissa Shofner demonstrated the patience and graciousness of a true believer as she tracked down permissions and potential reviewers. I should also thank the nameless marketing executive who suggested the book's current title, The Big Disconnect; it was a very good call.

There's just a bit more work to do before finishing the entire project, but meanwhile, dear reader, please enjoy my book.

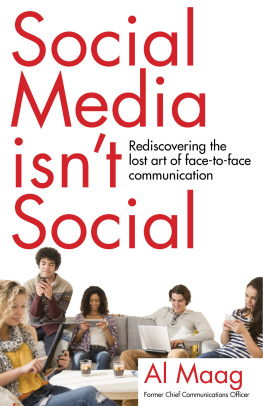

We have given our hearts to machines, and now we are turning into machines.

William Deresiewicz, Faux Friendship,

Chronicle of Higher Education, April 20, 2012

INCUNABULA

P aper or plastic, gentle reader?

By which I mean, are you reading these words as print on a traditional wood-pulp page or are they reaching you (as is increasingly common, these days) through electronic images of letters whose configuration changes with each new screen?

There is a real difference involved in your choice of literary delivery system, although it's not a difference of good or bad, as bibliophiles often claim. You may already know that book lovers say electronic books do not have the aura of a physical object: they can't be hefted or smelled. These same people go on about a print book's texture and tactility, observing that eBooks prevent you from enjoying the guilty pleasure of writing in the margins or turning down the corner of a memorable page. An author's signature on the title page might also bring to mind some personal impression of the man or woman who wrote a favorite book (although publishers are now working hard to overcome this).

Lastly, you can't hide photos, documents, or money in eBooks, something that sounds silly, unless you're artist-poor and suddenly rediscover a twenty-dollar bill marking a memorable passage in a well-read book, or unless one day you find an old snap of a much younger, skinnier man doing a dip with a much younger womannot yet his wifewhile both of their faces quite clearly show the first flush of love.

Notwithstanding these minor advantages of paper books, the longing for a palpable book-object is a familiar kind of nostalgia that disguises people's discomfort with new things and devices. A similar discomfort may be the birthplace of racial prejudice, but such anxieties always accompany technological change. In fact, the prejudice against the new is so strong, so fundamentally human, that in order to make new technologies more familiar and acceptable, the physical appearance of an older technology is always repeated in the design of the first generation of replacements. Our Neolithic ancestors may have experienced similar feelings when pottery replaced woven baskets. We know that the peculiar beauty of Anasazi pottery, for example, depends on its starkly linear geometric designs, an unavoidable structural necessity built into the warp and woof of the woven baskets that precede pottery.

And, in our own time, many eBooks have pages that need to be turned.

Okay. But there is a more significant difference between hard, paper copies and their electronic replacements, and this

Like all marketable items, paper books used to require human interaction and distribution. They had to be warehoused, handled, shipped, unpacked, and sold. In fact, until 1995, the act of purchasing a book demanded that you enter a bookstore, make a selection from a shelf, then interact with a human cashier as you completed your purchase. When you handed over your money, the cashier might say, Paper or plastic, sir? This might be the only thing he or she said, but it was human, and since it required an answer, something social happened. According to Jane Jacobs, it is the repeated process of such trivial interactions that establishes, over the course of time, social familiarity and trust, the intangible glue that holds our society together.

Next page