To Dr John Slade, my botanical uncle

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Chris Wlaznik and Morwenna Slade for their energy, inspiration and steadfastness: without them this book would not exist. And my children, for the times they had to make their own tea and for their willingness to pick fruit and embrace the adventure. Thanks to my parents, Marilyn and Roger, for support and encouragement. And to Uncle Johnny for all the trees.

For their rigorous proof-check and brilliant ideas, Rose Ward, Michelle Chapman and Janet Angus must be gratefully acknowledged, as must Danny and Sheila Daniels, whose pursuit of Streuobstwiesen went beyond the call of duty. Thanks to James Wong for crafting a sparkly foreword and to Andreas von Einsiedel for the shiny author photograph.

I am grateful to all the people I met along the road. The National Trust at Canons Ashby, Greys Court and West Green House; the many, and unstintingly kind, National Gardens Scheme garden owners, the Royal Horticultural Society, The Urban Orchard Project, the Kensington Roof Garden, Jason Ingram, Eric Sander and everyone else who was generous with images, information, locations and interviews. And, notably, the providers of context and stories the garden owners, juice-makers, orchard experts, horticulturists and random passers-by. Those who let me loose, gave me their time, told their tales and posed for pictures; the organizations and individuals across the world who responded with delightful generosity to being doorstepped for information.

Finally, my thanks must go to the team at Green Books: Niall and Sheila, Lindsey, Alethea and Jayne, for their magic touch.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

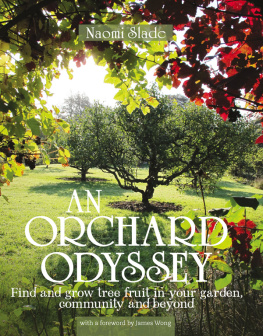

All over the world, small traditional orchards are under threat. Even in small domestic gardens, the enthusiasm for cultivating vegetables has far outstripped that for fruit. It seems fruit trees are mistakenly seen as being too big, too complex and unrewarding for modern gardeners. This book is the first step to changing all that. Preserving orchards is about so much more than bucolic nostalgia: if we lose orchards from our landscape, we lose not only a part of our heritage but also vital habitats for wildlife and a vast genetic repository that has taken thousands of years to develop.

Ditching the dusty tables of compatible varieties and pages of tortuous pruning advice of many of its predecessors, this is the first book I know to address the why of orchard growing as much as the how. Why are they so fascinating? Why are they under threat? Why is it so important we preserve them? I found this book fuzzily absorbing, like a horticultural fairytale. It tells of the rich history of orchards; of fascinating people, plants and places to inspire the reader. Yet, crucially, it also provides a practical roadmap to actually getting started even in the increasingly tiny modern garden.

Spot a tree in the landscape and understand how it got there, with the eye-opening tips found in these pages. Learn to plan, plant and maintain an orchard on any scale. Uncover the vital role orchards will play in the twenty-first century. Naomi has created an encyclopedic yet accessible resource for both novices and veterans, enabling us to re-engage with both why orchards are so vital and how to ensure their survival. Well done.

James Wong

INTRODUCTION

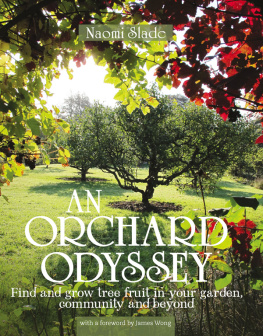

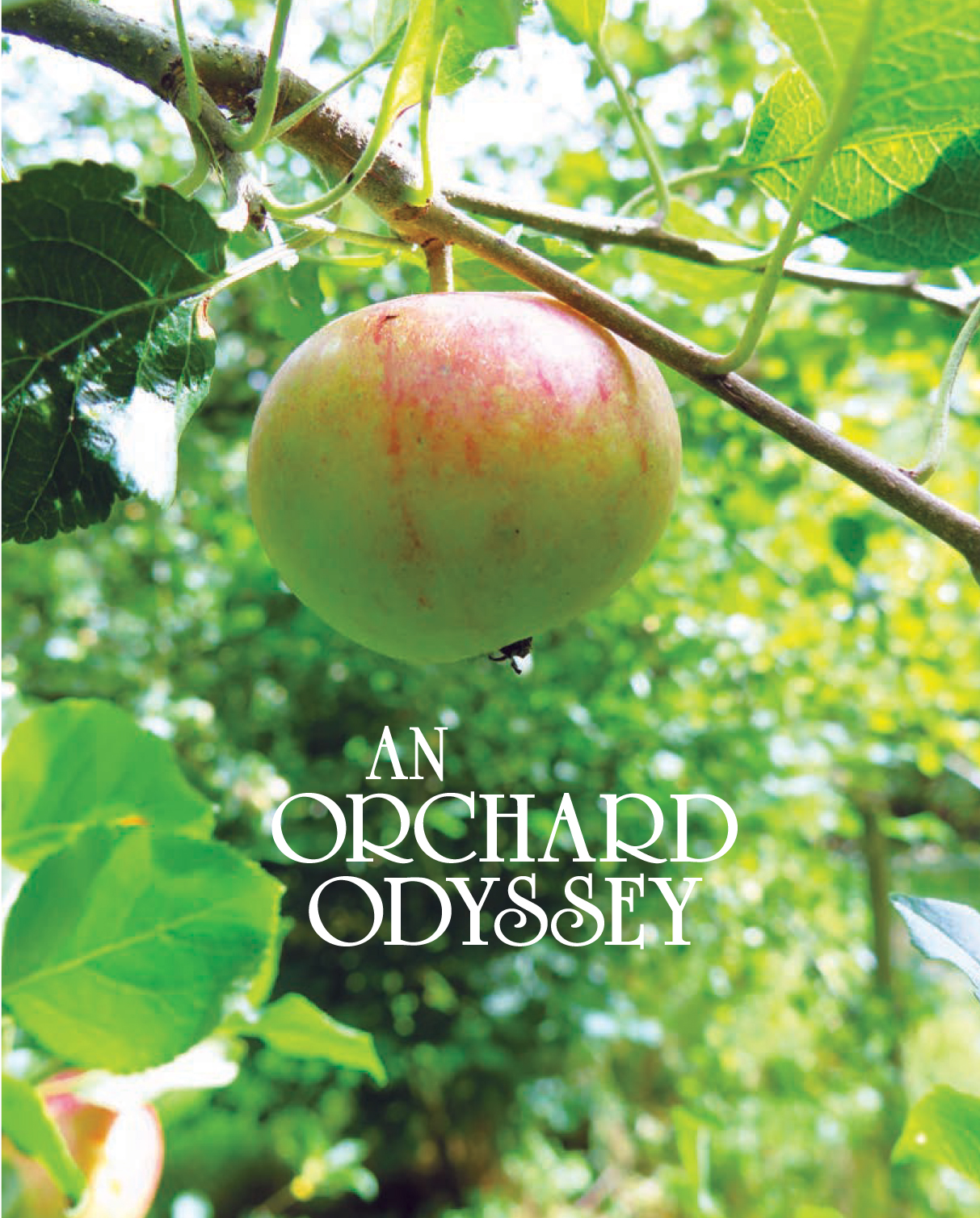

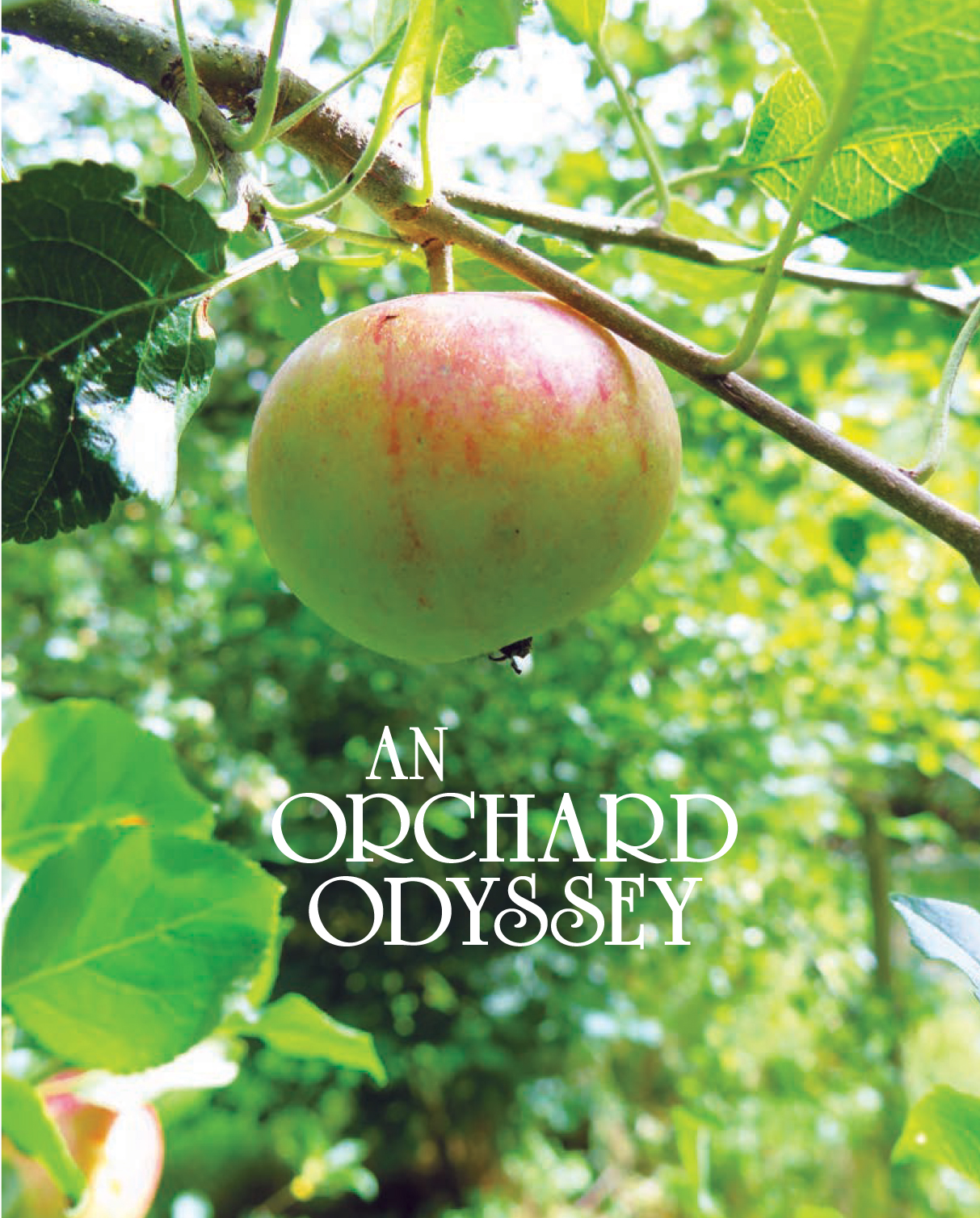

Orchards delight me. Exciting and compelling in their infinite variety and character, they speak to me on a fundamental level. I am intrigued by their history and folklore, and I love the embodiment of an ecosystem that is both stable and ancient. Amongst the trees the insects gently pollinating, the birds in the branches, the fruit quietly swelling in its own good time that is how it has been forever: peaceful and timeless.

In the depths of winter, the sight of a stray tree, still full of big yellow apples, is uplifting. A romantic confetti of blossom heralds each spring: first plum, then apple flowers, like bunches of miniature blush roses. The fruit-bright autumn roadside is a mystery of semi-wilderness; a miscellany of trees planted as named varieties and wildings that have sprung from discarded cores.

When the orchards at home are laden with their beautiful crop, dappled in sunlight or softened by mist, there is nowhere else I would rather be. They entice me to find a basket and get picking, to climb a ladder to the very top and swing there between the trees and the sky in the hope of reaching the highest, most perfect apples.

Fallen apples lie on the ground in late winter.

THE TRADITIONAL ORCHARD

Orchards have been a major feature of the landscape for centuries. Embedded in the collective psyche, they have huge social and cultural significance. They are filled with tradition and local colour and are singularly important for wildlife.

Time was that the orchard was part of the community. Every cottage would have a tree or two; every farm and country house would have a collection of fruit trees, however modest. They would provide food for family and workers: apples to eat fresh, to use in pies, to eat with savouries or to enjoy roasted in warmed ale and winter punches. Pigs and cattle would graze beneath the trees and there might be hay or mistletoe to cut. The trees would be wassailed in January to ensure a good crop that year, and harvested in late summer and autumn. They were part of life.

This garden has grown up around its fruit trees.

In the latter half of the twentieth century many traditional orchards were destroyed, while others are now succumbing to neglect and simply fading away. There is, perhaps, a feeling that their time is past; that this is a nostalgic idyll which, with our busy lives and high-rise lifestyles, we can only dream of restoring or enjoying.

The love of orchards has not diminished, but even in the countryside people have grown further from the reality. Collections of beautiful fruit trees are viewed with a retrospective melancholy. There is a sense that, although they have existence value, they are not relevant to contemporary life. A feeling that orchards are now out of reach, part of an unattainable tradition that has, regretfully, been relegated to a rural museum piece.

I disagree. And I believe that there needs to be a paradigm shift.

Next page