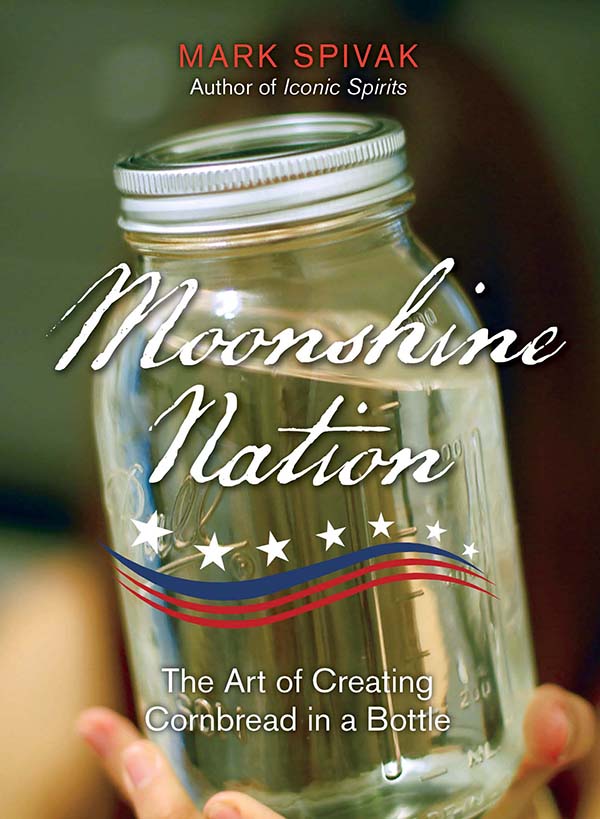

The Art of Creating Cornbread in a Bottle

Mark Spivak

Copyright 2014 Mark Spivak

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Part opener jar photo by Kelsey Pouk

Editor: Amy Lyons

Project Editor: Meredith Dias

Text Design/Layout: Maggie Peterson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spivak, Mark (Mark Allen), author.

Moonshine nation : the art of creating cornbread in a bottle / Mark Spivak.

pages cm

Summary: Moonshine Nation is the story of Moonshines history andorigins alongside profiles of modern moonshiners (and a collection ofdrinks from each) Provided by publisher.

eISBN 978-1-4930-1245-9 (ePub)

1. Distilling industriesPiedmont (U.S. : Region) 2.

DistilleriesPiedmont (U.S. : Region) 3. Distilling, IllicitPiedmont

(U.S. : Region)History. I. Title.

TP590.6.U6S65 2014

338.4'7663500973dc23

2014011011

For Carolann

All roads, rivers, and hurricanes

Contents

Introduction

Like many consumers, I believed that bourbon was the true American spirit. Its a good story, and distillers in Kentucky are adept at telling it. Bourbon, however, is basically aged corn whiskey, and corn whiskey was made in this country from the earliest days of the colonial settlers: Scots-Irish immigrants who traveled to the New World and brought their distilling skills with them. After the Whiskey Rebellion of 179194, those folks went underground and concocted their product in thousands of improvised stills throughout the Appalachian South. Their whiskeyunregulated, untaxed, and illegalwas made by the light of the moon and became known as moonshine.

As I researched the Whiskey Rebellion, I realized it was the source of many of the social and cultural divisions we see in America today. The widespread mistrust of the government throughout the South, as well as the resentment of the moneyed classes on the part of hardworking, rural citizens, is directly traceable to the events of 179194. Moonshining in the Appalachian South became both a source of sustenance and a way of life. In addition to being the only way to survive, it also became a symbol of the individuals resistance against forces beyond his or her control.

Moonshine today is legal in many states, and mason jars filled with corn whiskey populate the shelves of retail stores across the country. Even so, the attitudes of moonshiners havent changed much. Many of these men and women are descendants of generations of people who hid stills in remote spots in the backwoods and risked prison time to support their families. They are proud of their heritage and are committed to making sure that their ancestors way of life doesnt disappear.

The first part of this book traces the history of moonshine from the Whiskey Rebellion through the tax wars of the nineteenth century, and onward to Prohibition toward the present day. The second half consists of profiles of latter-day, legal moonshiners. These people welcomed me into their houses, sheds, and distilleries, shared their stories and their hospitality, and Im grateful for it: It gave me a glimpse into a freewheeling period of American history that is now being glamorized in popular culture. As I listened, I realized that many of the memories were bittersweet. Moonshining and bootlegging were hard and dangerous work; while a handful of people did get rich, most were engaged in a desperate effort to eke out a living.

The widespread appeal of moonshine today goes way beyond the product itself. Certainly, most modern moonshine is far better than the illegal corn whiskey once produced in backwoods stills. More importantly, it symbolizes a lost Americaa place free of commutes and urban blight, where people can defy the system and occasionally make the authorities look ridiculous. As I note in my profile of notorious moonshiner Popcorn Sutton, we all yearn at times to be the guy sticking his middle finger at society, and immersing ourselves in their stories helps us to play out that fantasy in our minds.

Of course, the current popularity of moonshine is connected to more than myth. Modern distillers are turning out a pure and carefully crafted product, and one that is extremely mixable. For those who want something to sip on, many flavored moonshines are delightful, especially since producers have become pickier about the quality of the fruit used for their infusions.

Most importantlyfor me, at leastis the fact that these are simply great stories. I hope Ive done them justice. Open a mason jar, make yourself comfortable, and settle in for some amazing tales.

Part 1:

Legacy and Legend

Marching on Pennsylvania

In October 1794, a force of thirteen thousand troops prepared for war in western Pennsylvania. President George Washington had raised the federal expedition, which was larger than many of the armies he led into battle during the Revolutionary War. They marched forward, prepared to put down an insurrection that threatened the sovereignty of the United Statesan uprising that had become known as the Whiskey Rebellion.

There was only one problem: The enemy we were about to confront was us. The president was marching the army to go to war with American citizens.

How did this astonishing situation come about?

In the aftermath of the Revolution, the new government of the United States was deeply in debt. When the Washington administration took office in 1789, that debt was slightly over $52 million, or roughly $1.3 billion in todays dollarsnot $16 trillion, to be sure, but a sum that the infant democracy found to be disturbing. The individual states were unwilling to repay their share of it. Aside from retiring that debt, the main goal of the new administration was to consolidate power under the umbrella of the federal government. Washington wanted to make the country he had founded into an institution that was truly the United States of America, rather than a collection of formerly rebellious colonies.

Alexander Hamilton, his ambitious secretary of the treasury, came up with a twofold plan. The first stage involved something called assumption: The new national government would assume responsibility for the debts incurred by the states during the war, thus ensuring that the states were permanently obligated to the nation. To pay for that assumption of debt, he proposed an excise tax on whiskey. This would not only retire the debt, but also pave the way for the ultimate sovereignty of the government, legitimizing its ability to tax citizens for anything and everything. It was a touchy and explosive idea, since the impetus for the American Revolution had been the unfair taxation imposed on the colonies by England.