Questions of German Spelling and Punctuation

Capital letters: In German capital letters begin (a) the first word of a sentence, as in English; (b) all nouns, as used to be done in Renaissance English, and adjectives used as nouns; (c) all forms of the polite pronoun Sie: Sie, Ihnen, Ihr; (d) all forms of the familiar pronoun, du and ihr, when used in a letter. Note that the word for I, ich, is not capitalized, unless it happens to be the first word in a sentence. Adjectives of nationality are not capitalized.

Der deutsche Bundeskanzler.

The German chancellor.

Punctuation: In general, German punctuation is the same as in English. There are only two major differences:

(a) dependent clauses are always preceded by a comma and followed by a comma, unless a final mark of punctuation is called for.

Das Buch, das von Dover verffentlicht wird, kostet zwei Dollar.

[The book, which by Dover published is, costs two dollars.]

The book which is published by Dover costs two dollars.

German does not distinguish restrictive and non-restrictive clauses by punctuation, as in English.

(b) a German infinitive phrase with several modifiers is set off by commas.

Er bat mich, ihm sein Gepck morgen ins Hotel zu schicken.

[He asked me, him his luggage tomorrow into the hotel to send.]

He asked me to send his luggage to the hotel tomorrow.

Umlaut , a word that has been accepted in English and which you can find in any better edition of Websters, is derived from then verb umlauten, literally, to change sound. The only sounds that can umlaut are a to , o to , u to , au to u. As you note these are all vowels or vowel combinations. The umlaut in German is indicated by the two dots that are placed over the changed vowel sound. In English too, we have the phenomenon of umlaut also referred to as vowel mutation. When man changes to men in the plural, or foot to feet , or goose to geese, or mouse to mice, we are actually also in the presence of an umlaut. In former times all the umlauted vowels in German were indicated by an e that followed the vowel and you may still encounter this spelling at times. The German poets name Goethe is a good example. Also cf.: Brger-meister, Buergermeister, Lwe , Lo e we. In fact, the little dots (also called diacritical marks) originated from the e which in the Middle Ages was placed above the vowel, this way  . Eventually the scribes became tired of writing the complete letter e and gradually it was transformed into first two small lines, and then two dots.

. Eventually the scribes became tired of writing the complete letter e and gradually it was transformed into first two small lines, and then two dots.

The Digraph B: In many German books the consonant combination sz is written as one character (B); it is equally customary to substitute double s (ss) for sz. This booklet, as well as Listen and Learn German, uses double ss, but you should also become familiar with the digraph, since you will encounter it in books and newspapers.

An Outline of the German Cases and Their Uses

This section summarizes briefly the four German cases and their uses. It is not intended to be exhaustive, but it will indicate the most important uses to which each case is put. For a discussion of the concept of case itself, see p. 113.

Nominative Case:

- The subject of a clause or sentence.

Das Lied hat eine schne Melodie.

The song has a pretty melody.

- Predicate nominatives (see p. 112 for a definition) after verbs of being, becoming, appearing, etc. sein (to be), scheinen (to seem), werden (to become), bleiben (to remain), etc.

Er ist der beste Reisefhrer.

He is the best guide.

Er ist und bleibt mein guter Freund.

He is and remains my good friend.

Er wird Lehrer.

He is becoming a teacher.

Genitive Case:

- Possession, attribution, materialin most of the situations corresponding to the English possessive in -s or the English of-construction.

Das ist der Pass meines Sohnes.

[This is the passport of my son .]

This is my sons passport.

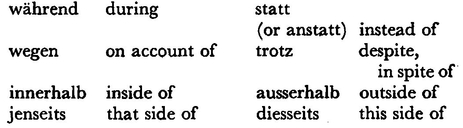

- With certain prepositions which always take the genitive:

Whrend des Regens waren wir im Kino.

[ During the rain were we in the movies.]

During the rain we were at the movies.

Statt des erwarteten Regens hat die Sonne geschienen.

[ Instead of the expected rain, has the sun shone.]

Instead of the expected rain, the sun shone.

Wegen des Regens sind wir zu Hause geblieben.

[ On account of the rain are we at home stayed.]

On account of the rain we stayed at home.

Dative Case:

- Indirect objects, as in English.

Er gibt dem Reisefhrer ein Trinkgeld.

He gives the guide a tip.

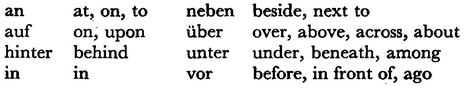

- With certain prepositions which always take the dative:

Sie kommt aus dem Haus.

She comes out of the house.

Er ist der Vater von fnf Kindern .

He is the father of five children.

(Most instances of the genitive given above in section Genitive Case, (a) may also be expressed by von with the dative, though the former is preferred.) Example: Das ist der Pass von meinem Sohn.

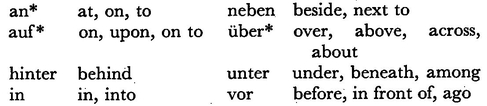

- With certain prepositions which take the dative in some situations and some meanings:

These prepositions take the dative when no change of position is involved. An easy rule of thumb consists of asking the question where ? or when ? (In other situations, involving change of position, or motion towards, these prepositions take the accusative.)

Er reitet auf einem Pferd.

He is riding on a horse. (Dative, no change of position is involved.)

Wir stehen vor dem Rathaus.

We stand before the city hall. (Dative)

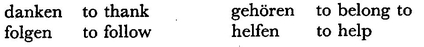

- With certain verbs that take their objects in the dative:

Der Koffer gehrt meinem Freund.

The suitcase belongs to my friend.

Accusative Case:

- Direct objects.

Wir schreiben einen Brief.

We write a letter.

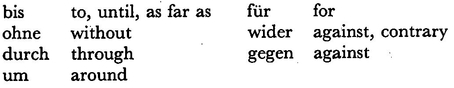

- With certain prepositions which always take the accusative

Wir fahren durch die Stadt.

We travel through the city.

Sie fhrt um den Platz.

She drives around the square.

- With certain prepositions which sometimes take the dative and sometimes the accusative:

These prepositions take the accusative when a change of position is involved. As easy rule of thumb is to ask where to ? They all involve motion towards something.

Wir gehen vor das Rathaus.

We are going in front of the city hall.

Wir setzten uns auf die Bank.

We sat down upon the bench.

. Eventually the scribes became tired of writing the complete letter e and gradually it was transformed into first two small lines, and then two dots.

. Eventually the scribes became tired of writing the complete letter e and gradually it was transformed into first two small lines, and then two dots.